OKLAHOMA BLUES

BY: SELBY MINNER AND IRENE JOHNSON

“Da-dut – da-dah-duh – dah-de-dup!” My bass rang out across the crowd… I could hardly breathe! He had me starting the song as a solo – indeed the whole set! Up the steps he came, out from behind the stage and into the light, sporting a yellow ice cream suit and a big red guitar. The drums kicked in, the rest of the band, and then… Mr. Lowell Fulson hit the microphone and the place came alive: “TRAMP! You can call me that! But I’m a LOVER!” I was holding the bass line – one of the greatest bass lines. The man at the top of the West Coast blues was back home in Tulsa, and Juneteenth on Greenwood was rocking! D.C. was wearing “old shiny” – his green and red tux jacket – with his red guitar, Big Dave 'Bigfoot' Carr was in from Spencer, OK, with his sax, Jimmy Ellis on guitar and vocals, and Bob ‘Pacemaker’ Newham on traps. It was 1989 and Lowell Fulson was at home to be inducted into the Oklahoma Jazz Hall of Fame. He later said he would come back to play the Traditions Festival in Oklahoma City in the fall, but only if he had the same backup band! Such an honor to play with an Oklahoma legend!

Oklahoma’s unique history and heritage provided fertile ground to grow its particular blues sound. Before we can dive into the blues, though, we need to travel back to Oklahoma before it gained statehood in 1907. I call it the wild west – where anything could happen.

Between the 1830s to 1850s, Native Americans of the Five Tribes were forcibly marched on the Trails of Tears from their homelands in the southeastern United States to the eastern part of modern Oklahoma, then called “Indian Territory.” With them, they brought their African American slaves. It must be understood that slavery in Indian Territory varied widely – ranging from resembling white cotton plantations, to commonly practicing intermarriage and allowing other extended freedoms. Linda Reese cites, “By the time of the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, the tribes' members owned approximately ten thousand slaves.”1

The Civil War was fought from 1861 to 1865. Dr. Hugh W. Foley, Jr. writes, “The Civil War’s presence in Indian Territory is directly related to Black pride in the area, as the Battle of Honey Springs, fought July 17, 1863, witnessed the first pitched combat by uniformed African American troops, the First Kansas Colored Volunteer Infantry Regiment, who fought alongside Anglo and American Indian troops. Fought just north of what is now Rentiesville, the battle has been called the ‘Gettysburg of the West.’”2 It was a running battle there at Honey Springs – some of it actually took place on our land where my husband D.C. Minner and I established the Down Home Blues Club (which hosts the Rentiesville Dusk ‘Til Dawn Blues Festival, the Oklahoma Blues Hall of Fame and the D.C. Minner Rentiesville Museum). Some of the soldiers from that battle went on to help found Rentiesville.

The end of the Civil War sparked big transitions for the “Twin Territories” of Indian Territory and Oklahoma Territory. Reese explains, “The government insisted on the abolition of slavery and the incorporation of the Freedmen [former slaves] into their respective tribal groups with full citizenship rights. All of the Indian nations were willing to end slavery, but citizenship rights conferred access to land and tribal monies as well as political power.”1 Despite tribal attempts to maintain control of their land and tribal monies through the U.S. courts, Freedmen were ultimately given full rights. The Dawes Act, which was the federal government’s way of breaking up commonly held tribal land into individual allotments, granted Freedmen “approximately two million acres of property, the largest transfer of land wealth to Black people in the history of the United States.”3

Reese goes on, “Freedmen from adjoining states had slipped into the territory for years, intermarrying with their Black Indian counterparts or homesteading illegally, but now the opening of Indian lands to non-Indian settlement gained momentum and brought hundreds of migrants both Black and white.”1 Oklahoma, considered the “First Stop Out of the South,” was indeed the “promised land” for about a 30-year window, offering land allotments and opportunity. It was close enough to the South to travel by wagon, folks could grow the same crops, and since it was not yet a state, there were no oppressive Jim Crow laws.

Freedmen often decided to settle together. It was at this point that the idea for all-Black towns developed. Larry O’Dell explains, “They created cohesive, prosperous farming communities that could support businesses, schools and churches, eventually forming towns. Entrepreneurs in these communities started every imaginable kind of business, including newspapers, and advertised throughout the South for settlers.”4 I’ve heard it said, the word was “tremendous opportunity, come help us do this… don’t come lazy and don’t come broke!”

The upshot of this opportunity was that more than 50 all-Black towns were established. These towns emphasized education, self-governance, strong churches and communities, and were held together by the economic security of their agricultural land. They believed that education was the key to a better future; the schools were strict and people graduated high school. My husband, Rentiesville native and bluesman D.C. Minner used to say, “If I did not get my lesson, I got a whoopin’ from the teacher. On my way home, my friend’s mom would give me a whoopin’, and when I got down here to the house Mama [his grandmother who raised him, Miss Lura] would give me a whoopin’, and she didn’t even want to know what I did wrong! If I got it from the others, she just had one coming too!”

Here’s where we can pick up on the music coming out of Oklahoma. Foley explains that the opportunities available during this time crafted the music legacy of the region; “Access to music lessons, instruments and mentors help explain why more African American musicians from Oklahoma developed the advanced musical skills necessary to evolve into jazz artists… As social and economic conditions changed for the state's African Americans by the 1920s and 1930s, more musicians born during that time period evolved into traditional, guitar-based practitioners of the blues.”5 Musicians who could read jazz charts went east and worked in almost every major jazz ensemble out of New York.

The jazz and blues players in Oklahoma were, in many ways, one community, particularly in major cities, such as Oklahoma City, Tulsa and Muskogee. In an interview with Bill Wax on Sirius XM’s B.B. King Bluesville, B.B. King said, “Jazz players say you can’t play good jazz unless you know the blues.” And D.C. said, “The R&B and blues bands here in the ‘50s and ‘60s all started their blues sets with an hour of instrumental jazz, so people could come in and get comfortable, and so the horn players could work out and do solos before they had to settle down to ‘blow parts’ – be rhythm players, essentially.” So, you see, there’s a blurred line there between jazz and blues here.

Given its history, plus the connection to Texas and the West Coast (you can drive to California without scaling the Rocky Mountains; there is a lot of work out there for musicians), I call Oklahoma – and Texas – “the cradle of the West Coast Blues.” Blues from Oklahoma is unique. Its sound includes horn sections, it’s a little smoother and the players dress – they consider themselves a little more “city” or “slicker.”

An integral part of Oklahoma’s blues sound developed with the Texas-Oklahoma “Hot Box” guitar style. Unlike the slide playing or finger picking styles from the Piedmont and Mississippi-Chicago sounds, the “Hot Box” guitar style is a single-note lead style that has a great local lineage that eventually crossed over to rock ‘n roll. Starting around 1900, players of this style include Blind Lemon Jefferson (possibly the earliest to record this style), jazz innovator Charlie Christian (the first to put electric guitar solos into jazz), T-Bone Walker, Freddie King, Stevie Ray Vaughan, B.B. King to Eric Clapton and beyond. The Hot Box single-note lead style is the style of most American rock ‘n roll to this day! B.B. King said in another Bill Wax interview, “I am from Mississippi, but my fingers are too lazy to play Mississippi style, I play Texas!”

There is no “music industry” per se in Oklahoma like there is in Nashville, Austin or Chicago; most people who play professionally work out of state. But since there are lots of juke joints in these towns – five in Rentiesville alone – there’s still a lot of music! Oklahoma has produced numerous great musicians and I’d love to tell about each and every one, but I’ll have to settle for highlighting just a few, with the help of Hugh W. Foley, Jr.’s “Blues” for the Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture.5

Hart Wand of Oklahoma City actually published “Dallas Blues,” the first 12-bar blues on sheet music, in March of 1912 – the same year W.C. Handy published “Memphis Blues,” widely considered the first blues song.

There were several territorial bands that played a circuit in the early 1900s across Oklahoma, Texas, Arkansas, Kansas, Missouri and Nebraska. The best of these bands was the Oklahoma City Blue Devils, which later became the core of the Count Basie Band out of Kansas City. Truly the bluesiest of all the touring jazz bands, I would say.

Jay McShann supplemented his passion for the blues with what he learned in the Manual Training High School band of Muskogee, OK, and went on to lead one of the great blues-based big bands of the 1930s and 1940s out of Kansas City. His "Confessin' the Blues" was one of the biggest selling records for a Black artist in the early ‘40s.5

Joe "The Honeydripper" Liggins charted a number of singles, including "The Honeydripper" and "Pink Champagne,” during the late 1940s and early 1950s with his streamlined rhythm and blues. His brother, Jimmy Liggins, led an amplified R&B group that preluded rock ‘n roll with hits like "Cadillac Boogie," "Saturday Night Boogie Man," "Drunk" and later, his now-classic blues song "I Ain't Drunk." Bandleader, drummer and songwriter Roy Milton’s “jump blues” served as a precursor to rock ‘n roll.5

Jimmy “Chank” Nolen was another of Oklahoma's important blues guitarists. Credited for inventing the "chicken scratch" guitar style, Nolen is considered the “father of funk guitar.”5 The chord on the guitar is played in such a way that is very percussive, like a drum beat. Since it makes guitar rhythms very danceable, James Brown picked Nolen up to record as primary guitarist on several major hits.

Gospel and soul-blues singer Ted Taylor experienced success with his falsetto-driven voice in the 1950s- ‘70s. Guitarist Wayne Bennett worked with Elmore James, Jimmy Reed, Otis Spann, Otis Rush and Bobby "Blue" Bland. Verbie Gene "Flash" Terry recorded the hit, "Her Name is Lou,” and later toured with T-Bone Walker, Bobby "Blue" Band, Floyd Dixon and others.5

Guitarist Jesse Ed Davis, a Native American with Comanche, Kiowa and Muscogee heritage, toured with Conway Twitty in the early ‘60s before moving to California and joining Taj Mahal. Davis’ “reputation led to sessions for Leon Russell, Jackson Browne, Eric Clapton, John Lennon, Ringo Starr and Captain Beefheart, as well as four of [his] own solo albums.”5

Larry Johnson and the New Breed (with D.C. Minner on bass) were the house band at the Bryant Center in Oklahoma City, playing several nights a week and backing up touring headliners like Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley for almost 10 years.

Lowell Fulson is probably Oklahoma’s most widely recognized blues guitar star. “By adding a horn section in the mode of swing bands to his electric blues lineup, Fulson created what is typically called the ‘uptown blues’ sound, which B. B. King made famous. Fulson's huge 1950 R&B hit, ‘Everyday I Have the Blues,’ became King's theme song”5 – surfacing the Texas-Oklahoma “Hot Box” guitar sound once again to evolve into what we know as the popular blues style!

Foley concludes, “Anglo-American blues men who emerged primarily from the Tulsa scene in the 1960s include pianist Leon Russell and guitarists J. J. Cale and Elvin Bishop.”5

I could keep going – multi-award-winning Watermelon Slim, extraordinary blues belter Dorothy “Miss Blues” Ellis, Jimmy Rushing of the Blue Devils and Count Basie's Orchestra, and so many more – but I’ll end my abridged round-up with my late husband, blues guitarist D.C. Minner.

D.C. was raised in Rentiesville by his grandmother, who owned and operated a grocery store/juke joint called the Cozy Corner in the 1940s- ‘60s. Here, he was exposed to all the music coming through. He toured, playing with Larry Johnson and the New Breed, Lowell Fulson, Chuck Berry, Freddie King, Bo Diddley, Jimmy Reed and Eddie Floyd before starting our own band, Blues on the Move. In 1988, we got tired of the road and moved from the California Bay Area back to Rentiesville, and reopened his grandmother’s old juke joint as the Down Home Blues Club.

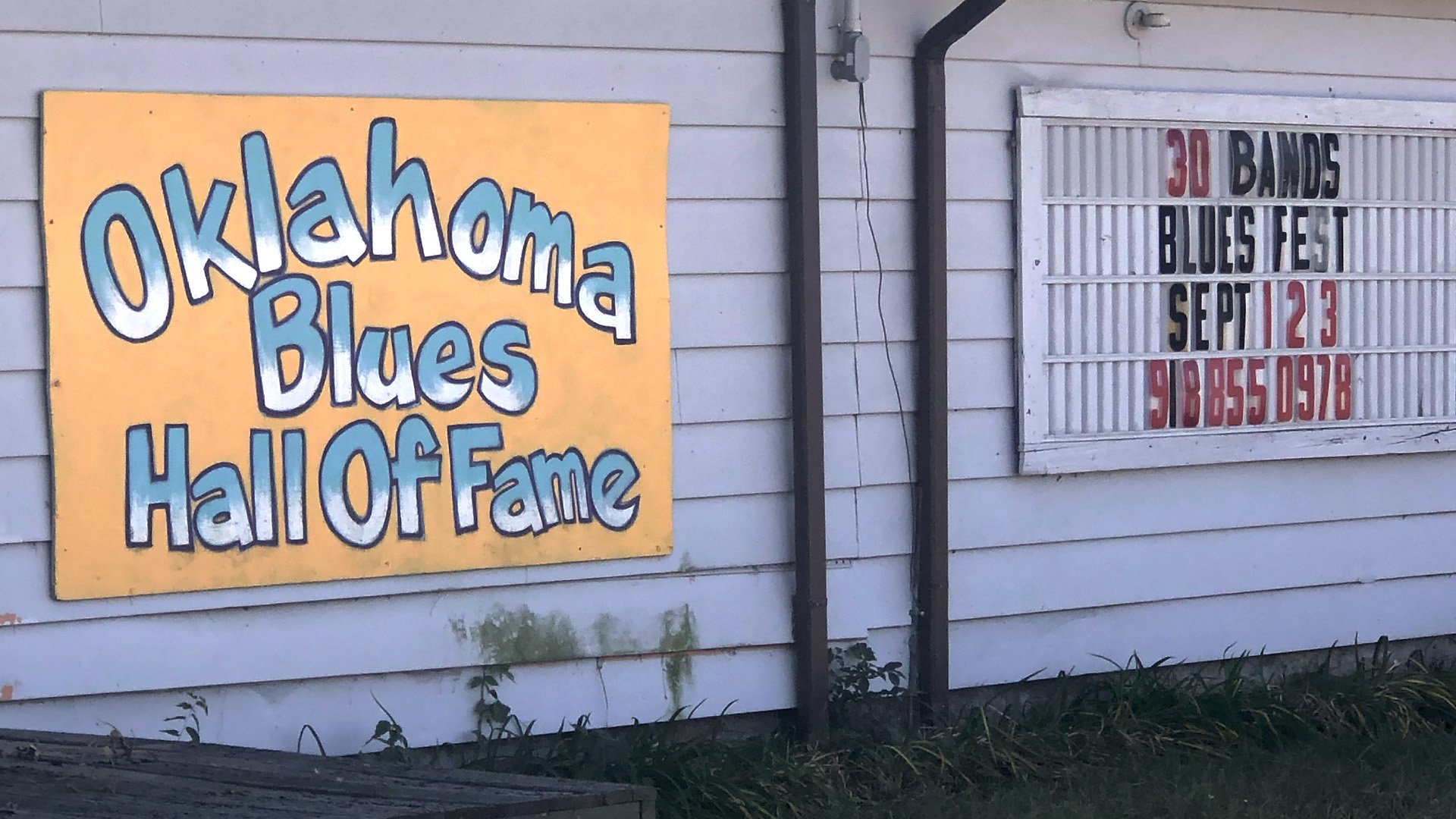

In 1989, we established the Blues in the Schools program through the Oklahoma State Arts Council. In 1991, we started the Rentiesville Dusk 'Til Dawn Blues Festival to feature local and regional blues artists, and it has become the longest running blues festival in the state and renowned nationwide. It’s here, where I also still run our other projects – the Oklahoma Blues Hall of Fame and the D.C. Minner Rentiesville Museum.

In 1999, we received the Keeping the Blues Alive Award from The Blues Foundation for our efforts and contribution to music education and blues history. D.C. went on to being inducted into seven Halls of Fame, including the Oklahoma Jazz Hall of Fame in 1999 and the Oklahoma Music Hall of Fame in 2003.

D.C believed, “This is one of the few places where this history is still left,” and I work diligently and joyfully to keep the blues – and this rich history – preserved and alive in Oklahoma.

Blues singer-bassist Selby Minner toured for 12 years with her husband D.C. Minner and their band Blues on the Move before settling in Rentiesville, OK. She continues to perform and teach, and keeps the Oklahoma blues tradition alive through her weekly Sunday Jam Sessions, the Dusk 'Til Dawn Blues Festival, the Oklahoma Blues Hall of Fame (OBHOF), and the D.C. Minner Rentiesville Museum. For more information, visit: DCMinnerBlues.com.

References

Linda Reese, “Freedmen,” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=FR016.

Dr. Hugh W. Foley, Jr, “From Black Towns to Blues Festivals,” Funded by the Oklahoma Humanities Council and the National Endowment for the Humanities. http://dcminnerblues.com/?page_id=167.

Victor Luckerson, “The Promise of Oklahoma,” Smithsonian Magazine, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/unrealized-promise-oklahoma-180977174.

Larry O'Dell, “All-Black Towns,” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=AL009.

Hugh W. Foley, Jr., “Blues,” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=BL016.

MAKE SURE TO CHECK BLUES FESTIVAL MAGAZINE FOR MORE!