Exploring the Past through Ring Shout in Paule Marshall’s “Praisesong for the Widow”

BY CHELSEA ADAMS

Scholars and writers often use the idea or geography of Africa to indicate a return-to-roots journey for black people. The focus of the roots theme is a temporal shift, moving from the present to the past to discover ancestral roots, ceremonies, and cultural traditions that existed before slavery pillaged and plundered tribal lands. While recovering and remembering these people, cultures, and traditions is important work, it is often used as proof of African evolution from primitive to sophisticated cultural formations. Romanticism of the past often contributes to the idea that at its heart, black culture has a “wildness” to it, instilling Western ideas about blackness to the cultural mainstream. David F. Garcia states in his work Listening for Africa: Freedom, Modernity, and the Logic of Black Music’s African Origins, that scholarly intent to establish proof of racial equality by focusing on black bodies may have unintentionally damaged the cause of freedom.

Looking at black music and dance development in both the US and the Caribbean, Garcia identifies how Western cultural standards dominated discussions of culture, focusing on how racialized and sexualized bodies represented the primitive and savage through performance. Using theatrical productions, film, and performance hall recitals that “reproduced” African dance as historical “evidence,” viewers and scholars alike came to believe in Africa as a space that had not changed over the centuries, a haven for historical origins to which each member of the African diaspora could trace their roots. The “evolution” of culture for black people, then, could be said to come from the influence of Western European standards, as evidenced by the achievements of African Americans. Such racial categorizations were vital in maintaining racial boundaries, associating new, popular music styles with African origins to keep societal norms in place, associating blackness with the primitive and “wild,” whiteness with advancement and sophistication.

According to Garcia, perhaps the greatest danger of this scholarly and now even popular practice is “these contexts’ blockages that transform sound and movement from affective flow to, for example, African and European, black and white, or primitive and modern music and dance such that people are made temporally and spatially distant from each other” (270). While Garcia acknowledges that it may be impossible to rid discussion of historical timelines and individual motivations, he does advocate for a more complete look at art forms instead of segmenting them into categories of black and white, us and them.

Garcia’s approach is useful when reading Paule Marshall’s Praisesong for the Widow, which at first seems to fit in the category of the back-to-Africa novel, one that offers a temporal shift that takes its main character, Avey Johnson, from a US, middle class society to a Caribbean, working class society to recover her cultural origins. Avey is able to participate in a blending of cultures, traditions, and names, where “as the names transcend their original identity, they enter a space of total possibility. Their combinatory potential is now virtually infinite” (Boelhower 23). The spatial shift from the U.S. to the Caribbean, to the island nearest Africa, serves not as a complete return to ancient traditions, but as a space to view the diaspora and new cultural growth, both Avey’s own and other diasporic cultures. I suggest that what is at stake in Praisesong for the Widow is the recovery of individual identity and expression through a remembrance of family, rather than purely ancestral, traditions that bring Avey to self-fulfillment as she reorients herself to accept that culture should exist outside of the Western understanding of cultural binaries. The main recovery tools are African American art forms that come from a combination of cultural traditions in the U.S.

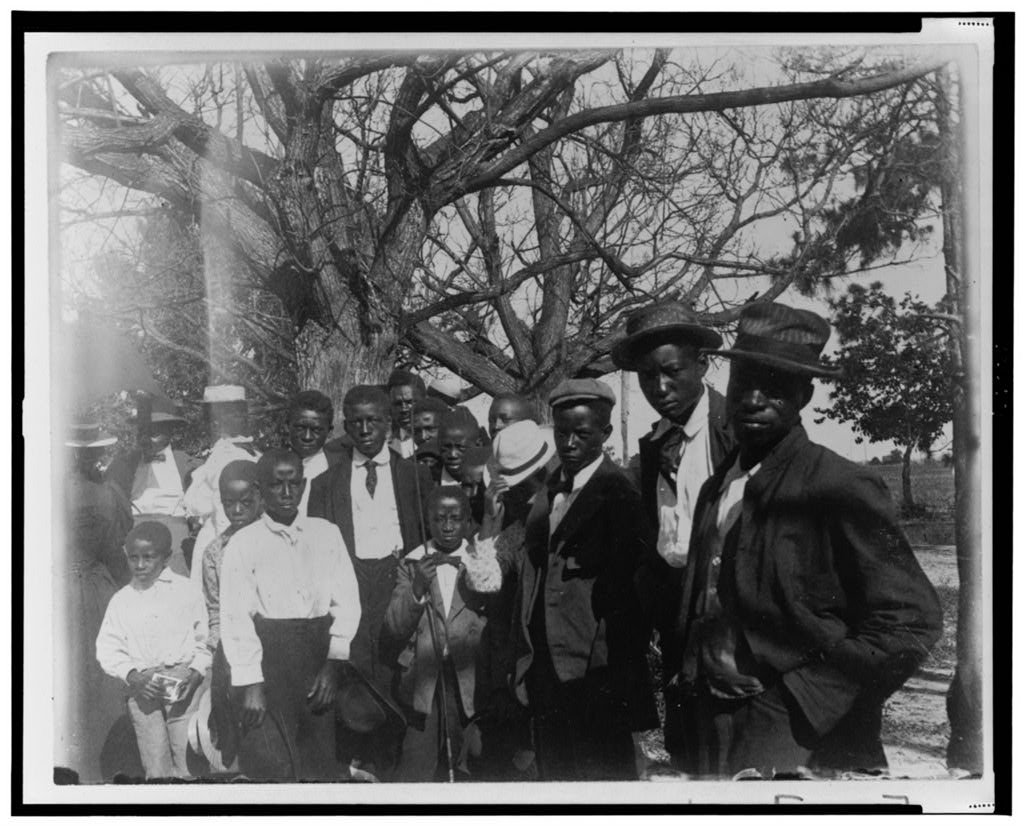

Avey receives cultural and spiritual renewal when she goes to the Big Drum ceremony on Carriacou. It is at the ceremonial proceedings that she reconnects with her Aunt Cuney through the ritual dance of the Ring Shout, and then her namesake, Avatara. Speaking of this event, where Avey becomes an active participant in the cultural traditions of the island, Lean’tin Bracks states, “The Beg Pardon dance is a crucial part of Avey’s island experience, for it proclaims that all are able to return to the celebration of ancestors, rituals, and traditions even after being lost” (116-7). Such a return through the Beg Pardon would not be possible for Avey, however, if it weren’t for Lebert Joseph and the elders in the group who sit in a sacred circle with “arms opened, faces lifted to the darkness, the small band of supplicants endlessly repeated the few lines that comprised the Beg Pardon, pleading and petitioning not only for themselves and for the friends and neighbors present in the yard, but for all their far-flung kin as well” (236). Without help, she would not experience the healing and renewal at the ceremony, because she does not know how to perform the ritual herself. The circle of elders holds significance for two main reasons: first, as Katrina Hazzard-Donald states, the sacred circles formed in ceremonial dances “represented a reality which connected one to the ancestors and reconfirmed a continuity through time and space” (196). The circle dance creates the opportunity for Avey to connect with her memories and her ancestral heritage to be filled with the strength and cultural knowledge. Second, as Bracks states, the intercession of the elders during the Big Drum Ceremony to offer up the Beg Pardon for their families and the world offers Avey an opportunity to see that “knowledge found in ancestral experiences is not only a function of historical memory as passed down from generation to generation, but also of current cultural practice that is available firsthand from those who are still alive. People of the diaspora can learn much from the living elders of their communities whose physical presence is a testament of their ability to survive and endure” (113). Before she attends the Big Drum Ceremony, Avey begrudges contact with the elders of black communities because they enshrined the very elements of black culture that she sought to run away from in order to fit into the middle class, white American mainstream lifestyle. At the Beg Pardon, she finally comes to understand and respect the role they play in such a sacred space, a crucial step to opening herself up to the wisdom they hold.

In fact, it is after the elders make intercession through the ritual that she can see someone who “seemed to be her great-aunt standing there beside her” (237). Like when Aunt Cuney used to take her to watch the Shouts performed in August, observing those “who still held to the old ways . . . slowly circling the room in a loose ring” (34), Avey watches the nation dances, her great-aunt spiritually with her on one side, Joseph Lebert with her on the other, explaining each dance they watch. Eventually, as is the nature of the circle dance, Avey must join in the performance. She spends time reflecting the open space they occupy begins to fill with dancers, expanding the longer the dancing goes on as more people join in the dance. The creole dances performed are a blend of many different African dance aesthetics that were shared across nations, meaning the space becomes more amenable to Avey’s participation.

When Avey finally joins the circle of older people and performs the Carriacou Tramp, she is performing a circle dance, the Ring Shout. The dances hold considerable similarities. According to Edward Thorpe, the dance “had certain affinities with the competitive Juba and consisted of a dance performed ‘with the whole body—with hands, feet, belly and hips’. The dancers formed a ring and proceeded with a step that was half shuffle, half stamp, and much pelvic swaying” (30). All the types of movement included in the dance are familiar to Avey, who has a long history of using the aesthetics of black dance as she danced to jazz music. According to Hazzard-Donald,

The shout ritual was the arena in which the motor muscle memory of African movement could be learned, sustained, relexified, and reborn eventually as secular dance forms. These forms would go on to become the famous African American dances that have circulated around the world; dances like the “Twist,” the “Black Bottom,” the “Pony” and, of course, the touch response partnering dance known as the “Lindy Hop” and all its various forms. (200)

The evolution of the dance allows for Avey to both be part of an older tradition and to be part of a new cultural tradition in the US. Even though Avey had not ever participated in a Ring Shout, she embodied the Africanist aesthetic as she performed the various dances done to jazz music, the Lindy Hop holding the greatest importance with its circular motion in partnership with another person. She holds a sense of ephebism and aesthetic of the cool as she slowly integrates herself into the dance. The elders in the circle dance, rather than try to teach her or push her out of the circle, welcome her in to work through the process and discover how her style of dancing can meld with their rhythms.

The moment offers a full realization of what it means to have African American heritage. Hazzard-Donald describes participation in the counterclockwise circle of the Ring Shout as engaging in “a ‘spirit-gate’ through which humans could connect to a higher spiritual reality” (203). That gate allows Avey access to what Hazzard-Donald calls “an intermediary religious form” which bridges the gap between traditional African religions and American religious forms (199). Barbara Frey Waxman discusses the importance of Avey’s dancing, because as

Avey carefully follows the rule of not letting her feet lose contact with the ground, a rule which metaphorically implies the principle of maintaining contact with her ancestral soil, her people, and their traditions. That is why Marshall calls this dance “the shuffle designed to stay the course of history” (250)—designed to subvert the drift of historical events that have prevented African Americans and Afro-Caribbeans from maintaining contact with their ancestral cultures. (98)

The dance she performs allows her to connect with her ancestors and reverence both her great-aunt and her namesake, Avatara; the dance allows her to finish healing from the spiritual malady caused when she cut herself off from her cultural heritage; and the dance allows her the opportunity to reclaim her past and look forward to the future opportunities she has to share her cultural knowledge with her own grandchildren. Avey is transported to Tatem and back to her childhood, where “under the cover of the darkness she was performing the dance that wasn’t supposed to be dancing, in imitation of the old folk shuffling in a loose ring inside the church. And she was singing along with them under her breath. . . . she used to long to give her great-aunt the slip and join those across the road” (248). In joining in the circle dance at the Big Drum Ceremony, she symbolically returns to Tatem to perform the Ring Shout with the church members, participating in a ritual she had longed to perform as a child but could not. The spiritual return to Tatem melds African-American and Afro-Caribbean traditions as everyone celebrates their shared African heritage.

It is this shared heritage on which Marshall ends her narrative, leaving readers to understand that the heritage Avey is to share is not purely African, but rather a rich mix of African and American heritage which make up her culture. Accepting the many influences of the diaspora is how to be self-fulfilled and a positive influence on continuation of cultural heritage. Doing so requires throwing out the linear, Western understandings of time and cultural evolution and replacing them with a circular understanding, which allows for the living and the dead to communicate shared wisdom and knowledge through generations as cultural tradition grows into new renditions and expressions of ancient values, which inspire new ways to deal with the present.

Works Cited

Boelhower, William. “Ethnographic Politics: The Uses of Memory in Ethnic Fiction.” Memory and Cultural Politics: New Approaches to American Ethnic Literatures. Northeastern UP, 1996, pp. 19-40.

Bracks, Lean’tin L. Writings on Black Women of the Diaspora: History, Language, and Identity. Garland Publishing, Inc, 1998.

Garcia, David F. Listening for Africa: Freedom, Modernity, and the Logic of Black Music’s African Origins. Duke UP, 2017.

Hazzard-Donald, Katrina. “Hoodoo Religion and American Dance Traditions: Rethinking the Ring Shout.” The Journal of Pan African Studies, vol. 4, no. 6, 2011, pp. 194-212.1.

Marshall, Paula. Praisesong for the Widow. Plume, 1983.

Thorpe, Edward. Black Dance. The Overlook Press, 1990.

Waxman, Barbara Frey. “Dancing out of Form, Dancing into Self: Genre and Metaphor in Marshall, Shange, and Walker.” MELUS, vol. 19, no. 3, 1994, pp. 91-106. www.jstor.org/stable/467874.