society

Structures, Identity, and the Making of Everyday Life

Shut Up and Play: A Brief History

Back in 2014, when Officer Daniel Pantaleo suffocated Eric Garner in a chokehold one long and hot summer day in Long Island, New York, scores of professional athletes decided to express their frustrations. Some kneeled while others donned shirts bearing the words, “I cant breathe” as a way to silently but visibly protest the continual confluence of Black death, racism, poverty, and endemic police brutality in the US. Many Black sports fans welcomed this expression of solidarity while many White fans did the exact opposite.

BY: COREY HARRIS

You've taken my blues and gone —

You sing 'em on Broadway

And you sing 'em in Hollywood Bowl,

And you mixed 'em up with symphonies

And you fixed 'em

So they don't sound like me.

Yep, you done taken my blues and gone.

You also took my spirituals and gone.

You put me in Macbeth and Carmen Jones

And all kinds of Swing Mikados

And in everything but what's about me —

But someday somebody'll

Stand up and talk about me,

And write about me —

Black and beautiful —

And sing about me,

And put on plays about me!

I reckon it'll be

Me myself!

Yes, it'll be me.

– Langston Hughes

Shut Up and Play: A Brief History

Back in 2014, when Officer Daniel Pantaleo suffocated Eric Garner in a chokehold one long and hot summer day in Long Island, New York, scores of professional athletes decided to express their frustrations. Some kneeled while others donned shirts bearing the words, “I cant breathe” as a way to silently but visibly protest the continual confluence of Black death, racism, poverty, and endemic police brutality in the US. Many Black sports fans welcomed this expression of solidarity while many White fans did the exact opposite. The reprisals came immediately: threats to end the athletes careers and public denunciation from the (mostly white) fanbase. “Shut up and play’ seemed to be the prevailing sentiment among a certain sector of the American populace. How dare these athletes ‘get political?’ They really should be thankful. Look at (insert a non-White, right-wing athlete or entertainer here)...why can’t you be more like him? Why do you guys make everything about race? If you don’t like it here, why don’t you go back to Africa?

As pro-football player (and disgraced welfare thief) Brett Favre confided to USA Today in 2021, “I know when I turn on a game, I want to watch a game. I want to watch players play and teams win, lose, come from behind. I want to watch all the important parts of the game, not what’s going on outside of the game, and I think the general fan feels the same way . . . I can’t tell you how many people have said to me, ‘I don’t watch anymore; it’s not about the game anymore.’ And I tend to agree.” Favre was speaking honestly. For a large majority of White Americans, the weekly gatherings of teams of well-paid Black people wearing uniforms should only be about the function that they are to serve for the fans and never about real problems of class division, poverty and police abuse. Pain is compartmentalized and then put on the shelf. Not now, not like this, not like that, this is not the time/how dare you. This thinking can be traced all the way back to slavery, during which the value of the enslaved resided solely in their labor and never in their ideas about freedom or anything else (even though Black ideas were stolen en masse for centuries to create White wealth). ‘The help’ was to provide a good experience for the paying public (to whom they owe so much) and nothing else should matter. Stop bleeding while you’re tap dancing boy; you’re spoiling my fun.

Many Black blues players have also been told to ‘shut up play’. Considering the beginnings of the modern entertainment industry in blackface minstrelsy of the 19th century, it should not be surprising that blackness is viewed as a commodity that dare not speak for itself or yearn for freedom. Indeed, the first blackface performers were White men, and even later in the century, when Black actors began ‘blacking up’ their faces for their turn onstage they knew that they were embodying a caricature, a White fantasy that could not exist in real Black life. This meant that it would have been ridiculous for them to employ the minstrel platform to speak out on the real issues of Black folk. (They had their own churches, communities, associations and families for that.) In fact, seeing real Black people onstage without shoe polish or burnt cork was considered an anathema, a horrifying insult to the genteel audience. The White psyche simply could not accept black bodies occupying the same space. They demanded a scarecrow. Thus the minstrel, as a creation of the White mainstream, continued to serve as the foundational model for Black performance in the US. Much of our vocabulary in speaking about race has not changed since the days of enslavement: people routinely speaking of their job as ‘the plantation’; your co-worker might boast about being the ‘HNIC’ at the workplace, some jest about being ‘worked like a slave’, while a supervisor is called the ‘overseer’; off-code Black folk are dubbed ‘Uncle Tom’ or ‘Sambo’ (we should read Uncle Tom’s Cabin again to realize that Uncle Tom was actually true to his people and an honorable man while Sambo was the betrayer, an agent of the slave master, but I digress). This minstrel mode is still very much with us, in every video depiction of Hennessy swigging, Philly blunt stankin’, crotch grabbing and encrusted-grill-grinning, young Black male rappers on the corner as well as every trope of the twerking, oversexed, long-nails-and-lace-front-hair sister with the tweety bird eyelashes and the loud mouth from around the way (Cardi B and Glorilla…y’all good?). The circus is alive and well. Racism, like Malcolm X said, is like a car. Every year they come out with a new model. Seen in the light of history, our present entertainment industry is only the newest iteration of minstrelsy. The only major difference is the loss of the burnt cork and shoe polish. The outrageous spectacle of Black debasement remains.

So how does one invoke blackness without the blackface? Therein lies the challenge that all non-Black practitioners of Black music in every era have had to navigate. Once the pendulum of social opprobrium shifted and open displays of blackface were seen as relics of a bygone era, all of the behaviors and practices of the former industry continued. Where once the only method of distribution in the 19th century was sheet music, the much faster means of technological repetition (phonograph, radio) and product distribution (air mail) in the twentieth century meant that the minstrel behaviors persisted and multiplied. There was never any break with the minstrel era. This made it possible for an actor like Al Jolson to rise to the heights of fame as a cantor gone bad in The Jazz Singer and be taken seriously, and decades later for Elvis Presley to imitate a Black Memphis swagger (while stealing the songs of Arthur Crudup and Big MamaThorton) that made the girls swoon. To say that the careers of neither of these early and mid twentieth century century artists (and thousands more) would have been impossible without Black music is obvious. I am saying that White artists’ embodiment of various tropes of Black behavior continue to inform and influence the direction of popular music around the world. Moreover, minstrelsy enabled a conception of blackness as merely a learned behavior that can be separated from the people who produced it and transformed into a commodity. Unsurprisingly, as in the minstrel era when the actors onstage were rarely Black and didn’t associate with Black folk, the portrayal of blackness in entertainment has continued to function as a malleable commodity that does not depict a real spectrum of Black life but rather enacts a repetitive material caricature of Black life, a phat and fantastical realm where all the women have long nails and fly-away hair with a BBL and a Gucci purse, and the men rock unlaced Tims and big beards while pushing shiny whips with oversized rims while their pants hang far below their derriere. Indeed, today’s minstrelsy is the prescribed trap house circus that now masquerades as ‘the culture’, streamed endlessly on any device to feed the addiction. The online, mobile, and voracious consumer culture sets the ever quickening pace.

The opening poem by the great Langston Hughes is as much a product of his politics as the disdain expressed for black music by those who like Black expression but don’t like Black folk so much. His reference to Broadway and Hollywood Bowl reminds us that for more than a century, blues music has been employed to spice up the blandness of mainstream American life. The Blues, that Black folk song form of obscure 19th century origins, is nowadays a mere commodity, a product on the marketplace that is bought and sold with as much regularity as water, land or clothing. And like other prized commodities, it is subject to the politics of those who produce, curate, package and sell it. Just imagine what the recorded blues legacy would sound like if every bluesman had been allowed to simply record the songs he knew (and that the folks back home loved) instead of continually being forced to record ‘a blues’ to keep the industrial money mill that was the race records industry running smoothly. The curators of the race record industry in the 1920s decided that no Mississippi bluesman should be recorded playing his version of Broadway or Tin Pan Alley tunes because the segregation of sound dictated that these Black people were isolated and marginalized country folk with little awareness of the outside world (a nod to Karl Hagstrom Miller). Such performances would directly challenge this entrenched view.

Besides, recorded music came on to the scene as a commodity and not an honest chronicle of Black musicking. These men ran a business to make money and not preserve Black folkways, so the question of ‘who would buy it’ determined their every decision. Even in the days after it could get a Black man swiftly lynched, mixing ‘politics’ with their entertainment was bad for the bottom line. This environment where White owned media, promotion and booking dominate is still the ever-present reality today. Business don’t give a damn about your culture…or your politics. This is a powerful sentiment in a country where Black political power has always been feared, thus it is violated, oppressed and controlled. What forms has Black political power assumed under the oppressive conditions of Jim Crow segregation in the US? As Dr. Greg Carr would remind us, this is an issue of governance. Who should govern Black people in America?

Google defines politics as “the activities associated with the governance of a country or other area, especially the debate or conflict among individuals or parties having or hoping to achieve power.”

In his classic work, In Search of the Black Fantastic, Black political theorist Richard Iton asserts that Black cultural expression is Black politics. He also has an answer for the question as to why Black culture is so endlessly creative:

Hyperactivity on the cultural front usually occurs as a response to some sort of marginalization from the processes of decision-making or exercising control over one’s own circumstances; what might appear to be an overinvestment in the cultural realm is rarely a freely chosen strategy. American blacks are not “different” in this respect because they have chosen to be but because of the exclusionary and often violent practices that have historically denied black citizenship and public sphere participation as problematic and because of the recognition that the cultural realm is always in play and already politically significant terrain. In other words, not engaging the cultural realm, defensively or assertively, would be, to some degree, to concede defeat in an important—and relatively accessible—arena. (9)

The organizing power of Black culture is precisely why Black political messaging that runs counter to the dominant political discourse is always suppressed or banned. Simultaneously, mainstream media and the political apparatus are not afraid of employing Black cultural tropes and stereotypes via mass entertainment to mobilize the Black vote. Witness the spectacle of Atlanta rappers Trina and Saucy Santana performing in a ‘no voting, no vucking’ video for the Democratic National Committee to understand the extent to which Black mass entertainment, stereotypes of Black promiscuity, and the over-sexualization of the Black body now drive how mainstream (liberal and conservative) Whites view Black folk. This is seen as a valid appeal to Black politics. There is no other constituency that is subjected to such messaging. This is by design. Thus political outreach to Black people assumes the minstrel form: it is portrayed as the White mainstream sees it, and to the benefit of the White mainstream. Like a grinning, shucking, and jiving blackface minstrel, it does not in any way align to real Black life nor real Black politics. The good news is that Richard Iton is here to tell us that the way Black culture is set up, we can do ‘politics’ (meaning address, discuss and creatively solve our own problems) even while we are suffering or having a good time. We don’t compartmentalize our trauma nor our joy. It infuses everything we do. This is in direct opposition to the European mind which goes to Africa and plucks sacred and everyday objects out of the fabric of everyday life, categorizes them as ‘art’, hangs them on the museum wall in the high-rent district back home and charges admission for ones to behold their ‘discovery.’ Such displacement renders the artifact mute. Extracted from context and meaning, it serves the function and meaning necessitated by those who control its new environment. Shut up and play all over again.

The real sentiment behind ‘shut up and play’ is that Black people should not govern themselves nor exercise political power. Black struggle has always been fueled by culture, by song: the catalog is full of union songs, anthems, gospel songs and protest songs. Judging by the profound impact of Black cultural politics in American life, it is extremely effective. Black entertainment, to the White mainstream, is a respite from the reality that surrounds them, an escape from the banality of their everyday existence. The history of suppressed Black political power in America has determined the modes of its expression. Denied for so long the ‘normal’ avenues of political agency, Black people’s everyday culture necessarily became a legitimate avenue of political expression. The challenge is now who will control and define this culture and to whose benefit. Black blues players who oppose the dominant white construction of blackness (otherwise known as ‘authenticity’) must take heed…and keep infusing their everyday git-down with the political. Because if Black folk don’t speak up, then no one else will.

Daryl Davis - Interviewing The KKK, Traditional Black Music, and more

Daryl Davis, a musician, author, and race relations expert was assaulted with flying bottles during the Cub Scout parade in 1968 when he was 10. This was his first experience with racism. He spent years studying and researching to answer the question he had about racial hatred.

Daryl Davis, a musician, author, and race relations expert was assaulted with flying bottles during the Cub Scout parade in 1968 when he was 10. This was his first experience with racism. He spent years studying and researching to answer the question he had about racial hatred. It would be a chance encounter later in life that would birth a dangerously intriguing project, documenting his search for the answers. As an entertainer, Daryl is an international recording artist, actor, and leader of The Daryl Davis Band.

He is considered to be one of the greatest Blues & Boogie Woogie and Blues and Rock’n’Roll pianists of all time, having played with The Legendary Blues Band (formerly the Muddy Waters band) and Chuck Berry. As an Actor, Daryl has received rave reviews for his stage role in William Saroyan’s The Time Of Your Life. Daryl has done film and television as well and had roles in the critically acclaimed 5-year HBO television series The Wire.

As an author, lecturer, and race relations expert, Daryl has received acclaim for his book, Klan-Destine Relationships, and his documentary Accidental Courtesy from many respected sources including CNN, NBC, Good Morning America, TLC, NPR, The Washington Post, and many others. He is also the recipient of numerous awards including the Elliott-Black Award, the MLK Award, and the Bridge Builder Award among many others. Filled with exciting encounters and sometimes amusing anecdotes, Daryl’s impassioned lectures leave an audience feeling empowered to confront their own prejudices and overcome their fears. More on Daryl Here:

SOUNDTRACK OF AMERICA

My plans for Tuesday night, the 9th of April, was to watch the premiering 1st episode of “Reconstruction, America After The Civil War” by Dr. Louis Henry Gates Jr. on PBS. Considering my work and platform speaks of and presents the reconstruction era often, I had planned to take notes then address my audience with my thoughts. However, that didn’t happen. As I was editing my next episode of Jack Dappa Blues Podcast, which featured sound bites from the Georgia Bluesman himself Jontavious Willis, as I raise awareness of the obscure African American Traditional Musician Elijah Cox, I received a phone call from The American Songster, Dom Flemons.

Dom called to invite me to a concert series he was performing in at The Shed Hudson Yard, located in the Heart of New York City. This was no ordinary concert series, and the Shed is no average venue. The Shed is a new creation, new construction, new idea grounded in the mission to be a civically engaged institution to commission artists in all disciplines to push boundaries and take creative risks. The Shed looks to produce, develop and present new works from tenured artists and emerging. To quote Alex Poots, the Artistic Director and CEO, “You,(the audience and artists) are an essential part of what it means to create a 21st-Century center for the arts in New York City. We’ll strive to be a stimulating creative hub and a home for all audiences.” The outside and the inside of this newly erected establishment reflects Alex’s statement. More so, the concert series I attended, which is the inauguration of the establishment, had extreme artistic energy. The series is dedicated to The Shed’s Founding Chair, Dan Doctoroff, and it was a presentation that is indeed up my alley.

I was truly amazed as I arrived at The Shred to see the world premiere of the 5 part concert series titled “Soundtrack of America” conceived and Directed by Steve McQueen. Best known for his Oscar Award-winning film, “12 Years a Slave,” McQueen steps on stage to share with the audience how he came up with this concept, and the questions he asks himself that ignited the passion for bringing such a concert series to fruition. He asked, “What would a timeline of African American music sound like? How would it evolve from slave spirituals to Motown, or even Badboy and WuTang? How would you demonstrate its breadth and global impact?” These questions led to a team of brilliant minds that put together an excellent work. For instance, Maureen Mahon, Chief Academic Adviser, and Professor put together the timeline, or family tree so to speak, that mapped the beginnings and progressions of what you all know I refer to as African American Traditional Music. Of course, and the highlight for me, you can’t have or produce anything of this magnitude without The Q himself Quincy Jones, who is on the project as Chief Music Advisor. Quincy attended the night I was there, sat in the balcony during the show, and greeted as many people as he could after.

The concert I attended was the third of the five-part series, and the performers were all Great! The night opened with the American Songster Dom Flemons who gave an entertaining musical history lesson of the early stages of African American Music. With a pan flute, harmonica and banjo, Dom go into a deep and rich musical performance that floored the audience. He even sang his Black Cowboy negro Spiritual tune “Black Woman” that presented the vernaculars and vocal inflections of Field Hollers and Black Spirituals of old, graciously explaining to the very diverse audience the true meaning and origins of Field Hollers, as he gave a vocally impressive example. His multi-instrument performance enamored the audience, and he wooed them with an instrumental with just a harmonica and many harmonica tricks. Immediately following Dom’s performance was the Fantastic Nigreto. He electrified the stage with his rendition of country blues as well as his socially and politically crafted original tunes that were doused in inspirations of blues, rock, funk, and soul. His interaction and engagement with the audience impressed me and reflected the Black musicians of yesterday that not only gave you a great show but left you feeling as if they came just to talk and play for you. A big part of African American Traditional Music is entertainment. Being an entertainer is no small matter, especially for working artists. Negrito’s musicianship, band lead, and vocals were well above the bar, added to his knack to keep the audience involved was a true homage to black music history.

By this point, my feet were tired, and I wanted to find a seat. The venue was an open standing space surrounding the stage. Behind and around the standing area, was more standing space that was set up like seating rows. I found a space on one of the stairs to rest, as the next act was called on stage by the legendary Greg Phillinganes, who was the Chief Music Director and lead keyboard player for the night. He and his band lit up the stage and backed up every artist on a level most bands dream of. So, as I sat, and the techs set up the stage, Greg approaches the microphone. I wondered who and how the next artist would approach this performance. As I drifted into thoughts about how I would start this article, I missed the last part of Greg’s introduction of the upcoming artist. I was aggressively awakened out of my self induced trance when the powerful voice and stage presence of Judith Hill engulfed the entire location. Her blackness, her vocal inflections, the way she controlled the stage and sang was the blackest performance I’ve seen and felt in some time. It was the black church, it was Beacon Theater Black Church Play, it was down-home blues, it was Motown, Stax and that Philly Sound we love. It was soul, blues, rhythm & blues. It was the pain we felt when we heard our favorite classic blues singer. It was the reminiscence of a time when women vocalist dominated the Blues scene. To top it off, after her piano blues performance or Dr. Feelgood, she then pays tribute to her inspiration, Ella Fitzgerald! After which, she turns around and walks off, a very seductive version of dropping the mic.

Moreover, that was just the third act. From that point, we had soft rhythm and blues, to REAL LYRICAL HIP HOP ( something that’s been missing for a while) to a young Nigerian man from London who sang a Smokey Robinson and the Miracles song, with a voice like David Ruffin. Remember, this was the third night. They were rocking for two shows already, and there were two more to go! Of course, I may have done things a little different; however, that doesn’t mean I didn’t enjoy the performances. The entire concept of the series is critical, and I hope it begins to open up doors for all of us who have been yelling, playing, belting and preaching African American Traditional Music for a while now. Not to mention, if the Shed lives up to its purpose, great traditional black music practitioners like Piedmont Blūz Acoustic Duo, Jontavious Willis, Marquise Knox, Christone King Fish Ingram, Veronika Jackson, Tito Deler (The Original Harlem Slim), Shelton Kotton Powe and many more will have the opportunity to play there. It’s worth checking out!

An American Hero & Anti-Hero Talks Reparations – The Story of Ari Merratazon

Published by: The African American Folklorist Newspaper (Lamont Jack Pearley Editor) Story and podcast producer Courtland W. Hankins, III (aka The President of Hip Hop)

An American Hero & Anti-Hero Talks Reparations – The Story of Ari Merratazon

Most of you are familiar with the movie Dead Presidents starring Larenz Tate. I bet you don’t know that Tate’s character was inspired by the real-life story of decorated war hero and Vietnam Blood, Haywood Kirkland – now known as Ari Merratazon. According to Mr. Merratazon, the heart of his life story actually began where the movie ended. If you remember the movie, it ended with Larenz Tate’s character being sentenced to prison after being convicted of robbing an armored truck. Mr. Merratazon did serve time in prison for armed robbery, however, it was to raise money for the Black liberation movement which he became a part of shortly after leaving the military.

Here is part two of Courtland W. Hankins, III (aka The President of Hip Hop) sit down with Mr. Merratazon to talk about his life and the reparations movement.

The Avery Alexander Story

Published By: Lamont Jack Pearley, video produced by WDSU News Project Community

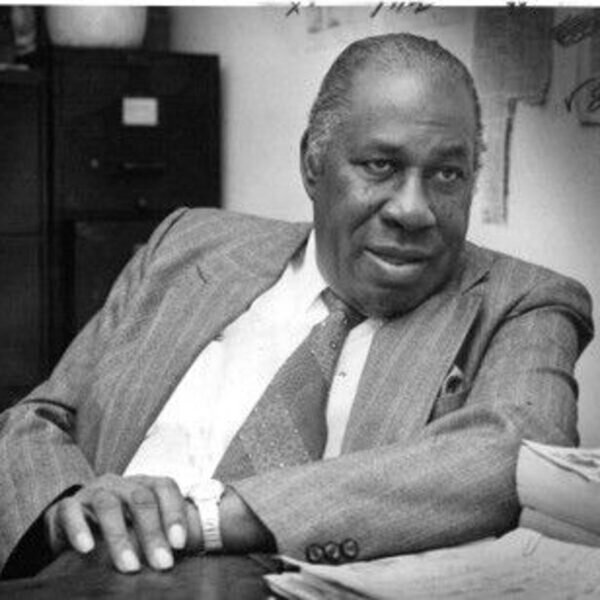

Avery Alexander

Avery Caesar Alexander was a Louisiana civil rights leader and politician. He graduated from Union Baptist Theological Seminary and was ordained into the Baptist ministry in 1944. He was elected to the Louisiana House of Representatives as a Democrat in 1975 and served in that office until his death.

Alexander participated in several marches with the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and in sit-ins to desegregate lunch counters. In a well-publicized and videotaped incident in the basement cafeteria at City Hall on October 31, 1963, he was arrested and dragged upstairs by the heels. In a similar incident in 1993, police used a chokehold to subdue Alexander when he participated in a protest against former Ku Klux Klan Grand Wizard David Duke at the Battle of Liberty Place Monument ceremony in New Orleans after Alexander repeatedly crossed police lines separating protesters and celebrants.

The City of New Orleans did not remove the Liberty Place Monument, which celebrated white supremacy, from the public space it occupied near the foot of Canal Street until nearly two decades later.

After becoming an ordained Baptist minister of the Union Baptist Theological Seminary, the Rev. Alexander joined the NAACP to become an activist within the historic Civil Rights Movement. Throughout his duration as an activist, Alexander performed many political stances upon segregation and racial discrimination in New Orleans. For instance, leading bus boycotts against racial discrimination of African-American employees. As well as his “lunch-counter sit-in,” in 1963, aimed to integrate public cafeterias. Continually, Alexander was even known to throw out wooden barriers used to racially separate whites from Blacks in streetcars.

Read more HERE

Chief Warhorse has worked with and was mentored by Reverand Alexander. According to the report of WDSU, “Alexander gave a voice to people with no voices as a legislator in Baton Rouge”

The article goes on to say, “That included Chief Elwin Warhorse Gillum, who is the chief of Tchefuncta Nation and the Chahta Tribe.”

Chief Warhorse is quoted saying, “Alexander stood alongside her in her fight to have Martin Luther King Jr. Day recognized as a holiday in St. Tammany Parish in 1983.”

Gillum continues “He made me feel that I could conquer the racism of St. Tammany as a woman because they had my back, I’m standing in front of this monument and it just gets me because he has always had my back.”