arts & culture

Honoring Expression Rooted in Memory and Movement

Boots On The Ground: The Viral Black Line Dance Movement Seen & Heard ‘Round The World

On December 20, 2024, Black America got an early holiday gift with the release of viral hit, “Boots on the Ground.” The trail-ride inspired song was the brainchild of 803Fresh, a South Carolina native and Southern soul singer who grows on me by the day.

Written By: Johnae De Felicis

On December 20, 2024, Black America got an early holiday gift with the release of viral hit, “Boots on the Ground.” The trail-ride inspired song was the brainchild of 803Fresh, a South Carolina native and Southern soul singer who grows on me by the day.

I remember my first time hearing the catchy track like it was yesterday. Black cowboys and cowgirls started sliding into my social media feeds, dancing to the song’s accompanying choreography. I was overjoyed to witness Black America reclaim a piece of our culture that others have merely cosplayed as their original invention: the line dance.

Atlanta resident Tre Little brought the sensational “Boots on the Ground” dance routine to life, conceiving the idea at work during a lunch break. The rhythmic choreography, a 32-count line dance paired with the clacking of folding fans, became an instant online success.

After posting the video, Little took a nap and later woke up to 100K+ views. Since then, there’s been a growing demand for professional dancers to teach the choreography through YouTube tutorials and line dance classes, often populated with Black Americans eager to learn it for themselves. Little’s influence has greatly increased since sharing his talents with the world, receiving requests for more dances and routines.

“Boots on the Ground” features a country-infused hip-hop beat set to a feet-tapping tempo. It’s the epitome of Southern Soul. The song’s inaugural line, “Where Them Fans At?” is symbolic of a war cry for Black Americans seeking to stomp their worries away and leave them on the dance floor. The saying, “Boots on the Ground,” is nothing new in the line dancing community either, though 803Fresh has given it a redefined meaning. Unsurprisingly, the viral hit reached No. 1 on Billboard’s adult R&B airplay and R&B digital song sales charts.

Photo Credit: Jesse Plum

The resurgence of Black cowboy joy has been long overdue, from celebrities like Shaquille O’Neal giving a nod to the “Boots on the Ground” movement to Beyoncé’s Cowboy Carter winning the Grammy album of the year award. I have yet to attend a line dance party or rodeo this year, but I have my cowboy hat and boots ready for when I do get around to it. I often wondered why Black cowboy representation was so scarce in the media, especially since I’ve experienced it myself, living in the South. Perhaps we can attribute the lack of awareness to the whitewashing of our culture. Colonization within the music industry has led the masses to believe that our musical contributions are limited to hip-hop and R&B, when that’s simply not the case.

We didn’t just step into the country music arena—we are country. Charley Pride, Linda Martell, and other Black blues and country legends paved the way for all country music artists to make the genre what it is today. And this may come as a shock to some, but our people never stopped line dancing. We’ve been performing routines at weddings, family gatherings, and school PE classes, featuring songs like the “Cupid Shuffle” by Cupid and the “Cha Cha Slide” by DJ Casper, who is no longer with us. The tracks may have an urbanized spin, but they still count as line dance music.

The lines are a bit blurred regarding line dancing’s origins, but historians believe that it was born from a gumbo pot of different cultures. From Indigenous tribal dances (e.g., the stomp dance) and Black American rituals (e.g., the ring shout) to traditional European folk dances, all played a role in the inception of this global phenomenon of a dance style.

There’s nothing more empowering than us moving as one, whether that’s on the dance floor or in how we approach circumstances that affect our community as a whole. There’s nothing more liberating than choosing joy over fear, sadness, and defeat. Gathering to perform these synchronized routines is a way for us to not only have a grand ole’ time, but also strengthen the ancestral connection on these lands and widen our pathway to collective healing.

I was born into two lineages with Southern roots. My mom’s parents hailed from South Carolina, and my dad and his parents are from North Carolina. As someone who has traveled a lot and resided in multiple states throughout the U.S., Black Southern culture’s influence on the entire nation—and the world—has been too evident to ignore.

Living in California opened my eyes to the impact in an unsettling way. Witnessing outside groups appropriate our culture without giving credit where credit was due irked me to no end. And don’t even get me started on the South. Watching country artists deliberately try to exclude and shut out Black country artists from achieving mainstream success is pure comedy to me. Little do they know that we’re not new to this—we’re true to this.

On one end, we have a group of people who outwardly hate us because they ain’t us. On the other hand, we’ve got culture vultures just along for the ride so that they themselves can benefit from our likeness. Nonetheless, it’s our right and responsibility to preserve the culture that we created in its entirety. My mission is to do just that through my musical and creative endeavors.

I am undeniably proud of 803Fresh’s modern twist to this niche music genre. The global attention on Black line dancing has reintroduced marginalized communities to a different way to protest in light of racial tensions, social injustice, and the sour political climate. Instead of marching in the streets, many are marching in formation to the sound of feel-good and uplifting music—not giving any attention to those seeking to elicit a reaction out of us. This time around, we’ve traded our picket signs for colorful fans. The “Boots on the Ground” movement has simply reminded Black Americans that we can still rest in joy despite the world being on fire.

What Did We Do?

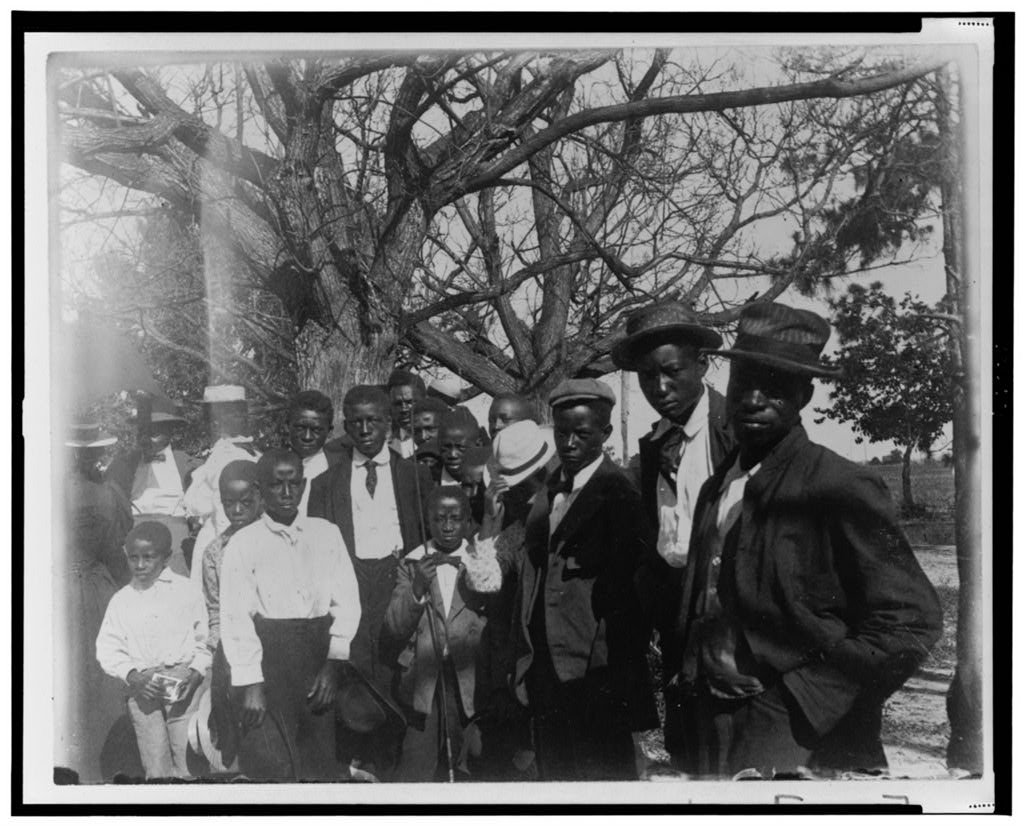

Image by: Unseen Histories

Poem By: D. Parker

What Did We Do?

I can’t help but ask,

what did we do

to make them hate us so much?

Written By: D Parker

I can’t help but ask,

what did we do

to make them hate us so much?

What did we do,

but live?

But breathe?

But want the same right to be free,

to be treated as human?

What did we do?

What did we do?

What did we do?

Is it because our melanated skin

glows like fire in the sun?

Oh, I know… I know.

It’s because we refused to work for free.

Because we learned our worth.

Because we stand proud,

even under the weight of centuries of pain.

Is it because we know that Black is beautiful,

that we honor our heritage,

and bow our heads in gratitude to our ancestors?

Or is it fear,

fear that one day,

we might treat them

the way they have treated us

since they chained and carried our people away?

Fear that we will rise from the breaking of our spirits,

scarred but unshaken,

burn with a flame

they thought they could dim?

Our DNA remembers.

The pain is etched deep,

like a mark that never fades.

Our bodies carry it.

Our voices carry it.

Our spirits carry it.

So I ask again,

what did we do

to make them hate Black and Brown people

so much?

What did we do?

What did we do?

What did we do?

It's all small steps to a giant, I know this to be true and with these steps, we will continue to rise!

D~Parker 9.16.2025

A Review of Ryan Coogler’s SINNERS

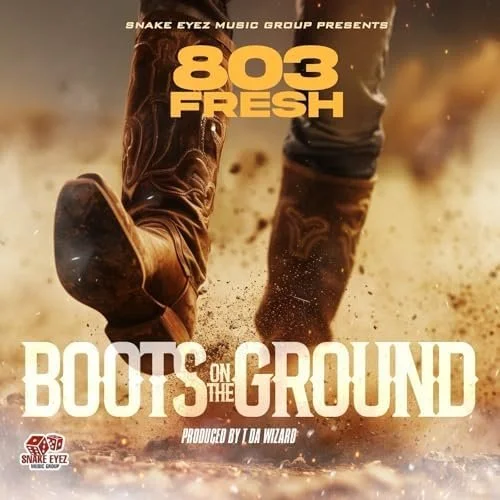

I’ve been thinking a lot about that film. It’s the first film that I’ve watched at least three times. I have my criticisms of it, but I also think that it is a masterpiece. When we compare that movie with anything produced anywhere in the world, it is an artistic masterpiece aesthetically. It is overflowing with symbolism from the “jump.” Everything from the opening scene with “Lil’ Sammy” and the introduction of the “Smokestack” twins is overflowing with rich historical and humanistic themes.

By Dr. Katrina Hazzard

I’ve been thinking a lot about that film. It’s the first film that I’ve watched at least three times. I have my criticisms of it, but I also think that it is a masterpiece. When we compare that movie with anything produced anywhere in the world, it is an artistic masterpiece aesthetically. It is overflowing with symbolism from the “jump.” Everything from the opening scene with “Lil’ Sammy” and the introduction of the “Smokestack” twins is overflowing with rich historical and humanistic themes. The sacredness of twins, among many African ethnic groups, is undeniable; so is the referencing of twins in ancient literary and mythological themes as far back as mankind can remember. The duality of human nature is a concept that is a Cultural Universal. The Yoruba Esu, the principle of uncertainty, duality, and choice is an example of reverence for this universal principle. So also is the African-American Br’er rabbit another example of the trickster duality. Man struggles with himself in this film, religion with Hoodoo, urban Chicago with rural Clarksdale, non-white with white, assimilation with cultural resistance, male with female, and canopying it all is imperfect good struggling with evil.

It has a few places where it could have been made more potent, but everything from the colors, the music, the presentation, and timing of the characters is outstanding and looks as if it were done with care. I absolutely loved Delroy Lindo‘s character, Delta Slim. He delivers one of the most important lines in the film when he tells Sammy “blues wasn’t forced on us like that religion, we brought this from home,” “what we do is sacred and big.” He says that what “they,” the blues men, do is sacred. Near the final scene Lindo becomes a reference to Jesus Christ himself, arms outstretched, as if nailed to a crucifix, blood spurting from his veins having been self-inflicted, with an Irish beer bottle, he presents himself as a living sacrifice in a ritual of profane communion as the vampires devour his flesh! He remains standing between his community and the greater evil.

The location and time of the ethnic mix of roles is a potent presentation of the American “racial and cultural mix,” particularly in dancing and music. That the three vampires are Irish is a reference to the Irish role and the American slave system, but it also speaks to the elements of cultural exchange from both sides of the black-white divide. Though this movie takes the form of a vampire film, it truly is much more than a mere “horror flick.” This film is exciting from the beginning, in which little Sammy, scarred-faced, referencing traditional African scarification rituals, literally stands in the doorway of the church. The doorway is one of Esu’s locations. He stands there in the portal between good and evil with a broken neck of an “instrument of the devil.” By centering the music known as the Blues, the filmmaker allows the concentric circles of previous and contemporary music and dance forms to radiate. The blues, more than any other form of American music, has lived a contested duality: certain elements from the music and the dance have moved freely between the church and the “Jook,” later known as the juke joint. Prior to WWII, a clear distinction between sacred and secular was still opaque and minimally extant for many African American folks. Thomas Dorsey, the father of American gospel music, was Ma Rainey’s songwriter before he became saved and began writing sacred gospel music; and many of the most successful and seminal Black vocalists have come from “the church.” The Black church has produced more great Black vocalists than Juilliard. As you see, my praise certainly outweighs my criticism of the film. Nevertheless, my minor criticisms are that Little Mary would have used the term “Negro” instead of saying that her grandfather was half-“black.” A “two head” woman, root worker, in the Delta in the 1930’s would not have said “Ashe” as she refreshed the mojo bag. The mojo bag that Smoke wore would probably have been worn around his waist with the bag hanging between his legs, and not around his neck. In the scene where the ancestors return and the roof appears to be on fire, I would have included a Michael Jackson character or James Brown visual reference. And I would have included someone in a choir robe “catching the Holy Ghost.” I highly recommend that all moviegoers, who enjoy well crafted films, see this great movie. I’m going to watch it one more time; there’s more to say, but I will stop here.

Pandemic Protests Collection By Larry Handy

The first protest I attended in 2020 here in Los Angeles took place on May 30th at Mariachi Plaza slightly east of downtown in the Boyle Heights district. LA which has a predominately Latino population showed up for George Floyd as did the rest of America

Editor’s Note | The African American FolkloristWe are honored to present a powerful new collection of poems by Larry Handy—work that blends lyrical precision with lived memory, cultural critique, and a deep understanding of Black folklife. More than verse, these are field notes in poetic form: rooted in personal testimony, shaped by collective struggle, and annotated with the clarity of a community archivist.This collection, Six Poems by Larry Handy, includes:Pulled Over (A View from the Curb)We’re In This Together (Covid19 Racial Rant)The Act of NamingI Still Remember LatashaProfiled…And We Still CoolGhazal for the Word Complete

Each poem is accompanied by a reflective annotation—layering the poet’s intent, backstory, and cultural context to illuminate the realities behind the imagery. These writings trace the intersections of protest and pandemic, memory and mourning, resistance and survival. They move fluently between spoken-word urgency and archival sensitivity, crafting a living document of Black American experience through the lens of Los Angeles and beyond.At The African American Folklorist, we are committed to platforming work that emerges from and speaks to Black communities, identities, and traditions. Handy’s poetic voice echoes the mission of this publication: to preserve, contextualize, and amplify Black lifeways on our own terms.We will be releasing this collection one poem at a time to give each piece the space it deserves—and to invite readers to sit with the weight, rhythm, and resonance of each individual offering.— Lamont Jack Pearley Editor in Chief

The African American FolkloristPandemic protests collection

written by: Larry Handy

Pulled Over (A View from the Curb)

They told me I look like someone they were looking for.

Sitting on the curb I was told I look like something they were looking for.

And who or what is it? Freedom? Their own soul? Their fear? Their aspiration? Their mirror?

Are you looking for Christ, officer? The moon is brilliant, have you looked at it? Why are you

looking at me?

Told to sit next to a cigarette butt. A cockroach shell separated from its antennae. White tweens in

SUVs making funny faces at me. This is the view from the curb.

To be treated like me, White friends get Mohawks, tattoos, and piercings.

To be treated like me, I just exist.

I will wear Hawaiian shirts in the cold…next time…

the anti-hoodie…next time…

maybe this will change things…next time…

Annotation

The first protest I attended in 2020 here in Los Angeles took place on May 30th at Mariachi Plaza slightly east of downtown in the Boyle Heights district. LA which has a predominately Latino population showed up for George Floyd as did the rest of America, but the city also brought to attention the Latino men and women who had been abused by law enforcement. Latinos that did not make the national news like Anthony Vargas, Jose Mendez, Christian Escobedo and eventually 19 days later on June 18th Andres Guardado, an 18-year-old security guard who was shot 5 times in the back while at work by LA County sheriffs. Mexicans, El Salvadorians, came out with Black Lives Matter masks and danced indigenous dances. Though they were not Black like me they held signs that said: “Black is Beautiful.”

What drove me to protest was my own experience with the LA County Sheriff's Department, dating back to the early 2000s. Despite having college degrees, voting, paying taxes, abiding by the law, and complying with the law, routine stop and frisks would still happen to me. While they never used racial slurs to my face, sheriffs would tell me to my face, “You look like a Black guy who did (fill in the blank)”, or “Black dudes like you like to (fill in the blank)”. I was even groped between my legs by female officers who were “looking for illegal items”. The humiliating thing about it all was no one apologized to me for mistaking my identity. No one apologized to me for making me late for work. No one thanked me for complying. After filing formal complaints against the LA County Sheriff Department failed, I gave up the fight but I didn’t give up the right to write.

Black folks have said in the past do not waste your time explaining racism to White folks. But I do. I do because I am a librarian and librarians answer questions. We were the first “Google”. And I tell White folks, if you have piercings, mohawks, tattoos, the world looks at you a certain way. Cops stare at you, courts frown at you, and employers doubt you. Well, my skin to the dominant culture is treated as though it were a mohawk, tattoo, and piercing. Some of them finally get it, while others just walk away, pretending not to understand.

The protests in Los Angeles came as karma to me. When Black, Brown, Beige, and White came together with signs, chants, and demonstrations, it was as though my formal complaints that were ignored finally got brought to light. Every step I took marching was a stomp upon the very streets that tried to kill my spirit. It may not come when you want it to come, but it will come.

We’re In This Together (Covid19 Racial Rant)

Locked in scared to go out told what to do by the government confused can’t find what you want loss of privilege sick family sick friends imprisoned no job worried how to pay rent Now you know what it’s like being Black. Waiting for covid19 reparations from the government see what I mean? You’re a nigger now.

Slaves in the same ship

Sickened by something strange

Sickened by something systemic

Sickened by something foreign to you

Sickened by something you didn’t create

Startled by stuff you didn’t start

Yep. You’re a nigger now.

Feeling worthless helpless feeling agitated not knowing when it will all end; now you know how it feels to be Black. Living 3rd world in the richest country in the world. Screaming power now! Yes, we want power! Now! Praying the power stays on—the utilities are due.

My people and I know this to be true.

To you and yours how much is new?

Annotation

I never loved using the N word. I never liked hearing rappers or comedians or brothers in barbershops using it. But for this one I had to. I tell people that the marginalized have a certain wisdom that the privileged don’t have. And while the privileged do have confidence and a spirit of adventure that the marginalized often lack, when things don’t go the way the privileged expect, they shatter. They become babies again. During the pandemic I watched the privileged get subjected to things they were not used to. They complained that they were oppressed because they had to wear a mask or were denied entry to a building because they didn’t wear a mask. And they complained that it was un-American and that the founding fathers were rolling in their graves. Well, prior to 2020 they also complained that people like myself complained too much about racism and injustice. Funny how Karma comes. It may not come when you want it, but it comes.

The Act of Naming

For many on earth

The only thing they name is their child

Their pet

Their pain

For me I’ve named thousands of things—

Poems, mostly

Choice by choice

Voice by voice

It never dawned on me I am an Adam in my own way

See? There I go again naming things.

Trump has named you the China Virus

The Wuhan

Kung Flu

I call you fate

Plague

Peter for Peter PanDemic

Never Never in my land

Could I ever ever imagine

You could fly

you could fly

you can fly

from sea to shining sea

Peter

Welcoming the dead to Heaven’s gates

Blowing your Covid horn

As the dead walk

Though gates

TRUMPeting the dead

Though Heaven’s

gates

Annotation

Trump is proof that White Privilege exists. There is no way a Black president would be able to make up words like “Kung Flu” and not be called “ghetto” or “gangster” or “jungle”. Trump did it and got praised by his base. I grew up in an era where rap and hip hop were fledgling. Rap was treated as the bastard son of disco, just an experimental passing fad. I remember when rappers said things on wax and the religious right wanted them banned for indecency, inappropriateness and inconsiderateness. That same religious right has elected a gangster rapper in orange face. Trump has many similarities to television evangelists. They preach off script as the spirit leads. They promise miracles. They cast out demons. They (some of them) survive scandal. They are anointed by the “whole armor”. Trump preaches off script as the spirit leads, Trump promises American miracles, Trump casts out Mexicans and Muslims, Trump survives scandals, and his miracle ear that was shot but not shot off was anointed by some type of armor. Christians relate to Trump because they relate to television evangelists.

What I wanted to do in this poem was play with words the way rappers do, the way Trump does and throw in Christian imagery the way television evangelists do. As Don King would say, “Only in America!”

I Still Remember Latasha

I Still Remember Latasha

50 stars in rows or 13 in a circle

We’ve wished upon them all.

Dragged into war like Sandra Bland’s cigarette

We’ve touched cotton and steel

Woven freedom in quilts

Dug our own ditches

To the tune of God Bless America

So, let’s stand for Betsy Ross’s graven image

Or kneel

Whatever your choosing

Black Lives Matter or Boston Massacre

Kapernic or Cris’ Attucks

Revolutions come in cycles

Kill time with history

The mystery isn’t lessened once you know

1619 was a long time ago

But I still remember Latasha from ’91.

Shot in the back before Trayvon in 2012

Michael and Tamir in 2014

Freddie in 2015

And George last week

Remember those names but remember hers.

Before body cams

Cell phones

Social media and distance

Before Trump

While a Democrat was in office.

See? The party doesn’t matter.

We matter.

And we’ve died under them all

13 in a circle or 50 in rows.

Annotation

This is a very important piece to me. Rodney King was beaten by 5 LAPD officers on March 3, 1991. It was filmed on tape and seen across the world. But it was Latasha Harlins, a 15-year-old girl, 13 days after Rodney King on March 16, that triggered outrage among Black folks in Los Angeles. Latasha was shot in the back and killed by a store owner over a bottle of orange juice. Had she been alive in 2020 to watch George Floyd die on screen she would have been 44 years young.

Black Lives Matter is a complicated term. It is a folk term because it is not copyrighted, and is for all to use. It is an organization, but it is also a rallying cry. A slogan. A belief. Many people who oppose the organization confuse it with the folk term. And though there have been scandals involving the organization, the folk use must still be upheld.

Black Lives Matter the organization, when it holds meetings, rallys and protests, it conductions a formal water ritual common among African peoples. The libation. In 2020 BLM leaders would poor a drop of water on the street and the crowd would say the name of a deceased person killed unjustly or a deceased elder. “Say his name. George Floyd [water poured]. Say her name. Breonna Taylor [water poured]. Say his name Ahmaud Arbery [water poured]. Say her name. Sandra bland [water poured].” People began running out of names and even the musician Prince was shouted out. “Say his name. Prince! [water poured].” Chadwick Boseman, the esteemed actor who played Thurgood Marshall, Jackie Robinson, James Brown, and superhero Black Panther died on August 28, 2020 of colon cancer and in Los Angeles—the city of stars—his name entered the BLM libations. But it saddened me that Latasha Harlins was rarely mentioned. And I believe partially it had to do with her death being so long ago that it had not impacted the younger generations of activists and protestors.

As an archivist/librarian by day I have a special place in my heart for memory. Nowadays if something isn’t posted on social media it hasn’t been posted in the mind. I wrote this poem as a poetic libation to Latasha Harlins who I remember.

Profiled…And We Still Cool

THE GOOD KIDS

SEVEN IN BLACK HOODIES.

We still cool

Them streets is our school

Learning cops cruise late

Our edges stay straight

Too sober to sin

Soda is our “gin”

Store robbed in June

They’ll blame us soon

Annotation

I had to commit blasphemy with this one. The great Gwendolyn Brooks wrote “We Real Cool” and I had to write my own version of it. The poem speaks for itself. The unique thing that I found during the 2020 Los Angeles protests was the presence of punk rock culture largely brought on by the White allies who joined us. It was in their defiance, their dress, their leaflets and flyers and their “ACAB” slogans. They took inspiration from the Anti-Racist Action punk movement of 1988 started by the Minneapolis “Baldies”—a group of White and ethnic kids of color banning together to kick out the neo nazi-skinheads who were assaulting immigrants and people of color. Punk rock is very folk. I had a music professor explain it to me. When it is your birthday no one cares how good or bad the song “Happy Birthday” is sung at your party. It is sung by everyone and what matters is that it is sung. Punk rock songs are like “Happy Birthday”. It is about the gathering. In my personal life I have embraced the punk rock philosophy of the straight edge made popular by the band Minor Threat. Straight Edge teaches strength through sobriety and sobriety fuels one’s resistance to control and injustice through clarity of thought. In this piece I incorporated the straight edge image.

Ghazal for the Word Complete

Teddy bear and shovel and afternoon sun

A child slides alone in her own park complete

Last week I let go of a man who died

Stages of breath show a life complete

Covid came and we masked our world tight

We prayed our trials would be complete

Songbirds pitch their 10-minute tweet

Peppered at high pitch the wind is a radio

Complete

Time can be squandered on pleasures and treats

And soon without warning the year is complete.

Annotation

My final protest of 2020 came the day after the elections. Wednesday, November 4, 2020. Nationally Trump had lost to Joe Biden which the world watched, but locally Los Angeles protestors were focused on the district attorney. The incumbent DA Jackie Lacey ran against the challenger George Gascon. Black Lives Matter Los Angeles led by Dr. Melina Abdullah challenged District Attorney Lacy on many issues. BLM Los Angeles held Wednesday protests outside the Hall of Justice every Wednesday for 3 years beginning in 2017. This protest was a gathering in celebration, District Attorney Lacy had lost. Despite Jackie Lacey being the first woman and the first African American to serve as District Attorney in Los Angeles, both BLM and the ACLU held her responsible for not prosecuting police offers for their actions and for accepting donations from law enforcement unions which they felt was a conflict of interest.

Everything was polarizing. If it wasn’t about race it was about power and if it wasn’t about power it was about the virus that stopped the world. We had no Summer Olympics because of the virus. Movie theaters shutdown and so I went to drive in theaters. Sports channels were showing reruns of old games and when they finally had current games teams played under quarantine to a fake crowd. The Los Angeles Lakers won the NBA championship. Los Angeles Laker Kobe Bryant died in January kicking off the year which possibly inspired the Lakers to go on and win the NBA championship 9 months later as well as the LA Dodgers that same month. The same people who criticized Kaepernick for kneeling, began taking knees themselves—coaches alongside players.

I was a caregiver working an essential healthcare job on the side. Since many senior citizen centers were closed, I worked with older adults in their homes, and I happened to be with one while he passed.

Many people in my profession, the profession of modern American poetry, turn away from the pastoral. “Poems about nature don’t move me / I want something that says something / A tree doesn’t speak to me.” This poem was my middle finger to that way of thinking with the image of the songbird. We need to listen to nature more because it will summon us back whether we go peacefully or go kicking and screaming.

SPACED COWBOY: A REFLECTION ON SLY STONE

On Friday, June 6th, 2025, three days before Sly Stone joined the Ancestors, I received in the post a lost album by his band, Sly & the Family Stone, called The First Family: Live At Winchester Cathedral 1967 (High Moon Records). When I was giddy to get a press release last week announcing this project, there was no sense that Sly would soon be leaving this earthly plane, and his loss is a shock, especially amidst Black Music Month. So this earliest live recording of him and his hyper-legendary group that

transformed soul, pop, funk, rock, gospel & psychedelia is most welcome.

Written By: KANDIA CRAZY HORSE

On Friday, June 6th, 2025, three days before Sly Stone joined the Ancestors, I received in the post a lost album by his band, Sly & the Family Stone, called The First Family: Live At Winchester Cathedral 1967 (High Moon Records). When I was giddy to get a press release last week announcing this project, there was no sense that Sly would soon be leaving this earthly plane, and his loss is a shock, especially amidst Black Music Month. So this earliest live recording of him and his hyper-legendary group that

transformed soul, pop, funk, rock, gospel & psychedelia is most welcome.

The First Family was captured at Redwood City, California’s venue, Winchester Cathedral, where Sly & the Family Stone served as their resident band between December 1966 and April 1967. Their debut album, A Whole New Thing, would be released in October 1967. This live album will be available digitally, on CD, and LP, with the latter formats containing liner notes by producer Alec Palao, interviews with Sly Stone and his family

of band members, and unearthed photos, etc.

The First Family features the Family Stone that would soon be world- renowned in another year, minus sister Rose. The release’s opening track “I Ain’t Got Nobody (For Real)” has most of the hallmarks of their later songs, including funky organ and percussive horns. It is plaintive but upbeat. This set is devoid of banter between tunes, but Sly Stone kicks it off with a brief introduction: “This is an original tune!” Song two, a cover of “Skate Now,” has a great breakdown with tambourine from Jerry Martini. Next, Joe Tex’s “Show Me” is like Sly being backed by the Mar-Keys and Bar-Kays, who supported Otis Redding live and in-studio. A few songs forward on an

actual cover of Otis’ “I Can’t Turn You Loose,” it foreshadows the tandem vocals that would become a key part of future Family Stone songs. And| their take on the traditional standard “St. James Infirmary” is dominated by wonderful trumpet from Cynthia Robinson that sounds pathos. Emerging from the period of San Francisco’s Summer of Love, when white hippies were appropriating black and indigenous cultures, these vintage soul covers foreground how Sly Stone would ultimately revolutionize music globally through his synthesis of the sonic styles au courant in that city then.

There’s been a lot of energy around Texas-born Sly Stone in recent times between the drop of this live album as a Record Store Day treasure in April 2025, the October 2023 release of his autobiography, Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin) A Memoir, and the Questlove documentary Sly Lives! (aka The Burden of Black Genius) from January 2025. I am still making my way through the tome, but I did see the documentary. I felt the first half charting his ascent was good, but the part that delved into Sly’s later years and dissolution suffered from not having him present in the film. Another demerit was the fact that Questlove did not challenge his friends

like D’Angelo to actually break down exactly what the nature and burden of black genius is and how it affected Sly or themselves as artists. Fortunately, in the obituary, Sly’s family has related that he recently completed the screenplay of his life story, and it will be shared with the world.

Almost immediately after the news circulated that Sly Stone had walked on and I posted some favorites of his songs – “Jane Is A Groupee,” “Stand!,” “Spaced Cowboy” – I thought of his friend and sonic contributor: Kentucky-born singer-songwriter Jim Ford. Sly said of Ford that he was the “baddest white man on the planet.” Ford dated my beloved Bobbie Gentry and perhaps composed one of her hits. Born in Paintsville, KY, he stated that

he came from a “very raw coal-mining background” and ultimately escaped it to follow the lures west to the Golden State. Out there, befriending them like Jimi Hendrix, he met indigenous musicians Pat and Lolly Vegas – later of Redbone – and collaborated on music with them. In an interview the month after I was born in 1971 on The Dick Cavett Show, Sly cited Ford’s

“beautiful” songwriting after stating: “In order to get to it, you gotta go through it.” When Dick Cavett queries, “Who said that Emerson or Thoreau?” Sly replies, “Jimmy Ford.” Apparently, Sly’s favorite Ford song was “Go Through Sunday.” Well, my most cherished of his tunes are “Harlan County” (“In the back hills of Kentucky, I was raised, in a shack on Big Bone Mountain”), “Big Mouth USA” (the slow country version), “I’m

Gonna Make Her Love Me,” the aptly named for our “roots are rising” times “If I Go Country,” “Harry Hippie” (also recorded famously by Bobby Womack), “Happy Songs Sell Records, Sad Songs Sell Beer,” and the stellar country-funk of “Rising Sign.” I must pause here to thank my brothaman, DJ Duane Harriott, and his fellow former Other Music employees in NoHo NYC for turning me on to Jim Ford when his lone 1969 album Harlan County – including arrangements by Lolly Vegas -- was reissued.

My most beloved country singers of all-time are Jim Ford, Gram Parsons, Kris Kristofferson, and Tom T. Hall. Among them, Ford is unique for having served as an inspiration to and worked with Sly Stone on his magnum opus There’s A Riot Goin’ On – he is in the album’s cover collage. Sly and Jim these two visionaries, were meant to make music together. Now they are together again in the Spirit World.

On his beloved song “Everyday People,” Sly Stone told listeners that “I am no better and neither are you / We are the same whatever we do.” His sister Rose declaimed “different strokes for different folks.” My favorite quote posted to my Facebook profile has always been: Different strokes for different folks & so on & so on & scooby-doo-bee-doo-bee Oooohhh sha- sha [“We got to live together!”]. This is what I truly believe.

I was born into a household and social milieu where Sly & The Family Stone’s music was ubiquitous. Sly’s impact on black music was everywhere on the radio and the stereo so seamless it seemed to have always been that way. Yet it wasn’t until I was around 13 years old and first saw the film of the 1969 Woodstock festival on PBS that the full magnitude of what the Family Stone had been was made clear. In thinking about Woodstock, it’s the black and brown performances that stand out and endure the most: (my prime musical influence) Richie Havens, Jimi Hendrix, Santana. And Sly, who came along with other psychedelic rock bands from San Francisco, exploding onstage at 3 am on August 17, 1969, driving through “You Can Make It If You Try,” a “Music Lover” medley, and the much-celebrated “I Want To Take You Higher.” The performance is so indelible and framed by the filmmakers such that it perpetually resonates as the apex of the Family Stone’s career in my mind. Sly provided a benediction for the freedom- seekers of Woodstock Nation.

Sly Stone revolutionized black music specifically and music in general with his funk and rock & roll innovations in the 1960s just as his black rock peers, Arthur Lee did with psychedelia and punk, and Jimi Hendrix did with upgrading the blues and by inventing eco-metal. James Brown is the progenitor of The Funk, but Sly took it in new directions and subsequently influenced everyone from Miles Davis, Herbie Hancock, the Jackson Five, The Temptations, Betty Davis, Parliament-Funkadelic (George Clinton was a close friend & collaborator), Earth Wind & Fire, and Stevie Wonder down through the songlines to Prince, Human League (“(Keep Feeling)

Fascination”), Public Enemy, Glen Scott (hear his melancholic and spacey “The Way I Feel,” which quotes Sly’s “Loose Booty” with its refrain “Shadrach, Meshach, Abednego”), Kendrick Lamar, and OutKast.

Sly Stone told Dick Cavett on another appearance in 1970: “everyone is an influence.” Yet few have had such a vast and stalwart imprint on popular music and culture as Sly, whose changes were not solely sounds and souls but also sartorial, as one of the male commentators in Sly Lives! ratifies. Sly was also a cosmic traveler who espoused a world view of black and white, men and women all living and being together on higher ground. Sly Stone influenced me through his particular genius; my song “Soul Yodel #3” from my debut solo album Stampede was directly from the Source of his “Spaced Cowboy,” which features him in soulful honky-tonk mode yodeling. I have also written a “Soul Yodel #1,” which I hope to record before the end

of 2026.

As a still-emerging artist in country-adjacent music, I have been in the trenches for ages, striving hard to make great music inspired by

Appalachian folk and other southeastern elements as an indigenous creator in a space counter to what the New York Times’s “In the Age of the Algorithm, Roots Music Is Rising” article from earlier in June did to belatedly acknowledge a long-standing “trend” and anoint certain come- lately old-timey and honky-tonk acts as predominant in the roots music sphere. When I reflect on my efforts, I can’t help but identify with the following “Underdog” lyrics by Sly Stone’s from the same year as the new live album since he deserves to be firmly situated on the rock & roll Rushmore and have symposia devoted to him and his works, among other laurels:

“Hey dig!

I know how it feels to expect to get a fair shake

But they won’t let you forget

That you’re the underdog and you’ve got to be twice as good (yeah yeah)

Even if you’re never right

They get uptight when you get too bright

Or you might start thinking too much, yeah (yeah yeah)

I know how it feels when you know you’re real

But every other time

You get up, you get a raw deal, yeah (yeah yeah)”

Today, as I have been scribing these reflections on Sly Stone, I saw the sad news of The Beach Boys’ Brian Wilson walking on. It’s so unbelievable within days of each other, we should lose the two certifiable musical geniuses of the 1960s. And I also happened to see both Sly and Brian live in their later years. Considering their mutual drug abuse and mental issues it was miraculous to see them in fine form. I fell in love with an ex at Brian Wilson’s Pet Sounds Tour installment in Philadelphia, PA at the Mann Center for the Performing Arts on Bastille Day 2000. Sly’s the Family Stone featuring Sly himself I also saw for free in Lenapehoking (NYC) at

BB King Blues Club off Times Square in late 2007. The chance to see Sly Stone in person was life-altering in itself, but to also see him play was divine. I don’t recall the setlist, but the excitement of the Family Stone experience persists.

At a time when America is again turbulent and its people in turmoil, the loss of Sly Stone feels like a shot straight to the heart. His open heart remains manifest in us all. As I delve further into his catalog anew, digging on other favorites like “Luv ‘N Haight,” “Runnin’ Away,” and “Time For Livin,” I ponder how I will continue to work Sly as inspiration into the music I make with my Native Americana trio Cactus Rose NYC. It is clear I must harken to his deep humanitarian messages and consider how to channel the ways he utterly transformed the world. And above all, follow Sly Stone Spaced Cowboy’s prime directive unto the Cosmos: everybody is a star.

Black American-Run Country Music Associations Needed to Make a Comeback—Here’s Why

On the heels of Beyoncé’s “Cowboy Carter” release, Black country artists had their mainstream moment amongst the genre’s fans. It was long overdue since it was us who helped create and pioneer country music, though racist industry politics have blocked most of our artists from shining in the big leagues.

Are predominantly white institutions (PWIs) the end-all, be-all answer to tackling the country Music diversity dilemma? I think not.

Written By: Johnaé De Felicis

Charley Pride

Becoming a trailblazing Country Music superstar was an improbable destiny for Charley Pride considering his humble beginnings as a sharecropper’s son on a cotton farm in Sledge, Mississippi. His unique journey to the top of the music charts includes a detour through the world of Negro league, minor league and semi-pro baseball as well as hard years of labor alongside the vulcanic fires of a smelter. But in the end, with boldness, perseverance and undeniable musical talent, he managed to parlay a series of fortuitous encounters with Nashville insiders into an amazing legacy of hit singles and tens of millions in record sales.

Growing up, Charley was exposed primarily to Blues, Gospel and Country music.

On the heels of Beyoncé’s “Cowboy Carter” release, Black country artists had their mainstream moment amongst the genre’s fans. It was long overdue since it was us who helped create and pioneer country music, though racist industry politics have blocked most of our artists from shining in the big leagues.

Reflecting on the genre’s beginnings, Indigenous pride comes to mind. Charley Pride, the first mainstream Black country artist, made big waves in this country music category. Yet, he experienced mislabeling in the same way that reclassified Indigenous Black Americans have in the U.S. “They used to ask me how it feels to be the ‘first colored country singer,‘ then it was ‘first Negro country singer,’ then the ‘first Black country singer.’ Now I’m the first African-American country singer.′ That’s about the only thing that’s changed,” he shared with The Dallas Morning News in 1992.

Before Beyoncé’s Cowboy Carter release, only a handful of Black country artists had achieved commercial recognition—Darius Rucker, Mickey Guyton, and Linda Martell, to name a few. Then you have accomplished artists like K-Michelle, who crossed over from R&B and other genres to country music, just to land back at square one and climb an uphill battle for a seat at the table.

To date, only three Black country artists out of hundreds have been inducted into the Country Hall of Fame. And while Nashville’s Country Music Association claims to champion diversity and inclusion, I can’t help but think that it’s merely a performative response to societal pressure. Industry gatekeepers still don’t welcome Black country artists with open arms, no matter how talented they are. We saw that with Beyoncé. Colonial-run institutions continue to move the line for what’s considered “country,” conveniently weaponizing this issue as an excuse to deny Black artists their deserved record deals and radio play. My observation of country music fans is that they don’t care if you’re black, white, yellow, purple, or blue. They just want damn good music. The institutions are guilty of rejecting many country artists of color by refusing to kick down their invisible white picket fence. Still, now that artists can directly reach their fans with social media, their “blessing” doesn’t matter anymore. It never did.

As an artist and creative of color, I think I speak for us all when I say that we are past fighting for acceptance in predominantly white spaces. With the rise of emerging Black country artists, the case for Black American-run associations comes into play.

The History of Black Country Music Associations

Cleve Francis, M.D.

Singer, Songwriter, Performer and Physician (Photo by Rena Schild)

In 1995, a Black country artist collective aimed to ‘unblur’ the genre’s color lines. With that came the Black Country Music Association’s inception. Founded by country performer Cleve Francis, the Association challenged the status quo and the narrative of our musicians and our music. They went out of their way to ensure that the underdogs were given their flowers and considered as more than an afterthought, opening doors that they otherwise may not have been able to walk through themselves. Francis departed from the organization in 1996, leaving country songwriter and performer Frankie Staton to become its frontrunner. The association cultivated a community amongst Black country artists magically. For example, they hosted their Black Country Music Showcase at Nashville’s famous Bluebird Cafe, a historic landmark and songwriter’s haven for testing new songs.

Thanks to the Black Country Music Association, ignored artists who needed a leg up in the business had an extra lifeline. The leaders, as country artists themselves, generously educated their successors on the industry’s ins and outs.

The Black Country Music Association had an active presence in the late 1990s and early 2000s but has since dissolved. Yet, its legacy continues to live on. Two years ago, the Country Music Hall of Fame acknowledged the Association in their exhibit, American Currents: State of the Music. Today’s younger organizations, like the Black Opry and Nashville Music Equality, carry the torch in fighting for industry equity.

From BCMA to Black Opry

The Black Opry

Black Opry is home for Black artists, fans and industry professionals working in country, Americana, blues, folk and roots music.

In 2021, researchers from the University of Ottowa found that the 400 country artists in the US include only 1% who identify as Black and 3.2% who identify as BIPOC. Organizations like Black Opry, a modern-day twist on the Black Country Music Association, seek to change that. Its community of Black country, folk, blues, and Americana artists is boldly ushering in a new generation of Black country artists. Founder Holly G. started the Black Opry in April 2021 to advocate for country artists of color. What started as a community blog has since expanded to a huge movement of emerging Black country artists. The Black Opry comprises more than 90 musicians who have been featured in over 100 shows to date. Black Opry acts get ample stage time to sing and perform on their instruments, with other members doing backup vocals, giving them equal attention and visibility. I’m proud of this community for creating a safe space for marginalized country artists, ensuring that they go through the music journey as part of a supportive and active community of performers.

Beyoncé’s Cowboy Carter release also opened the floodgates of widespread support for the Black Opry, as the album features members of the collective. The community exists as much for the fans as it does for the artists, further bridging the gap between the two groups. As a folk musician myself, I’ve come to realize that there’s an audience for everyone, regardless of skin color.

Supporting The Future of Black Country Music

Linda Martell

A pioneering force hailed as the unsung hero of the genre, Linda Martell (82), was the first commercially successful Black female artist in country music. Martell had the highest peaking single on the Billboard Hot Country Singles (now Songs) chart at #22, “Color Him Father,” by a Black female country artist in the history of the genre in 1969, until Beyonce’s “Texas Hold ’Em” debuted at #1 on February 21st, 2024. Martell was notably the first Black woman to play the Grand Ole Opry stage.

Black country pioneers who paved the way for today’s artists, from Charley Pride to Linda Martell, faced roadblocks that we likely couldn’t fathom. Today’s Black country music associations are in place to keep those following in their footsteps from experiencing similar obstacles. Thanks to technology and social media cutting out the middleman, opportunities in country music are now more accessible than ever. Supporting each other also goes a long way. Cowboy Carter introduced us to some newer Black faces in country music who have been putting in work for years, like Tanner Adell and Reyna Roberts. And then you have hybrid artists like Shaboozey and Breland who are innovatively merging the worlds of country and hip-hop.

These artists are what country music needs to evolve in a forward-moving direction. They’re pushing boundaries in a way that we haven’t seen before, and it’s a breath of fresh air. There’s no limit on how far these rising talents can go, especially with a strong, sustained community like ours backing them.

History Speaks: The Black Experience in Southeast Kentucky

The Black Experience in Southeast Kentucky is a series that shares the stories of African Americans living in the hills of Southeast Kentucky.

Written By: Emily jones Hudson

History Speaks: The Black Experience in Southeast Kentucky is a series that shares the stories of African Americans living in the hills of Southeast Kentucky. Our roots are deep in the mountains but have stretched beyond these hollowed hills. Voices from the past and present herald the presence of Black life in these mountains and quietly whisper: "We were here." "We are still here."

Emily Jones Hudson

I spent my early "growing up" years in Hazard, Kentucky struggling to reconcile my identity as and African American and an Appalachian. A Black person living in the hills of Southeast Kentucky. Coming Full Circle introduces my quest for identity and explains my passion to share the stories of African Americans living in these mountains, past and present.

Coming Full Circle was originally published in my book, Soul Miner, A Collection of Poetry and Prose, in 2017 and revised for my column, History Speaks: Voices From Southeast Kentucky.

Coming Full Circle

They say these mountains separate. They say these mountains isolate. When I was young and growing up in these mountains, they kept the world out. I grew up to embrace these mountains, their history and story; they became etched in my soul. I was raised up listening to my father’s stories of coal-camp life and to his version of Jack Tales; to grandpa’s stories of hunting in the woods, burying sweet potatoes in the ground, of working his farm up on the hill and a mine below the hill. These mountains’ hold grew strong on me.

It was not until I began my journey beyond the boundary of these mountains that I was able to meet you, my beautiful African sister. You told me stories from the Motherland, the cradle of civilization. I told you Mother Earth stories. You draped your body in a beautiful rainbow of colors. I dressed in blue jeans and hiking boots. And then we shared the woman-secrets passed down from mothers and grandmothers, from generation to generation. These woman-secrets kept them strong. They had to be strong to survive. We found a common bond. You taught me of the Motherland, and I began to understand why you walked so proud with head held high. We discovered that Motherland and Mother Earth were one in the same.

But soon the mystique of my mountains awakened from deep within and began to call me. I knew my journey was home bound. I wanted to bring my beautiful African sister home with me to meet my mountain sisters. You came. I now embrace a triad of cultures: African, African-American, and Appalachian.

Home. These mountains are home to me. Mother Earth. It was here in these mountains that I grew into womanhood. I say “grew” into womanhood because early childhood years were tom-boy years. I played rough and tough with my brothers. I thought I was no different. I climbed the apple trees in grandpa’s yard on Town Mountain. I climbed the coal cars that straddled the tracks across from my uncle’s house in Kodak. We built forts above our house and named them Fort Boonesboro and Fort Harrodsburg. I thought I was no different.

As I grew older, I learned to appreciate the mountains, their quietness and stillness. They became my friend as I would spend countless hours living beneath the treetops lost in my dreams. What did it mean to be a young woman growing up in these Southeastern Kentucky hills? What did it mean to be a young black woman growing up in these mountains? You see, I felt there was no difference.

I loved the life of tradition. I grew up watching my mother quilt, canned tomatoes and put up beans. My father grew corn upon the hill behind the house. I remember the Sunday trips to the coal camp to visit my Uncle Ralph and Aunt Frankie. It was always dusk when we would catch a glimpse of my uncle coming up the holler wearing coal dust on his face and carrying an old dinner bucket. I dreamed of writing music, playing my guitar, and becoming a country music singer. It seemed such a simple life. My mountains kept out anything that threatened to upset that simplicity.

And then I left the shelter of my mountains as daddy sent me off to college to follow my brother. Berea College welcomed me with open arms, and I found that I could still maintain some of that simplicity and Appalachian flavor. It was here during my college years that I was exposed to true cultural diversity. Coming from a small mountain town where everyone was related one way or another, I had never before seen so many people of color all together at once! I was introduced to my African brothers and sisters. I became enchanted and obsessed with finding my roots and discovering how they linked together. I was enticed to look into my mirror. I saw two women I did not know. The first woman carried a peace and freedom sign and invited me to march to Selma with her. The second woman walked so graceful with a basket balanced atop her head and beckoned me to join her at the Congo. I was intrigued and mystified and wanted to know more about the women who extended their hands in greeting to me from my mirror.

I began to learn about the rich African culture and how early civilization was there in the ancient cradle. I discovered a whole new world, and I began to think, “I have missed so much life while being rocked and sheltered in the arms of my mountains.”

Then an incident occurred that turned my mirror inside out. I was one of the founding team members that started the campus radio station, one of three African-American students and the only female. My program included contemporary rhythm and blues and many times I worked the night-owl shift. During my senior year as I began to think about graduation and job hunting, a friend convinced me to make a demo tape and send it to radio stations. I mulled it over in my mind. Three years’ experience working for the campus radio station. First female disc jockey. Surely, I would not have any problems finding a job with a radio station. I sent my resume and cover letter to a Black radio station in Indianapolis. I had visited relatives there often and that was the choice radio station to listen to. Before long I received a reply. They were so impressed with my resume and requested a demo tape. I put the demo tape together, rushed it to them and then played the anticipation game. I just knew they had a job for me based on their reply to my resume. Their second response, however, was not what I expected to hear: “There must be some kind of mistake. This can’t possibly be the same person on the demo tape that sent the resume.” And then there it was: “You don’t SOUND black! You sound like a hillbilly!” That is what they essentially said. I still have the demo tape buried in a trunk, but I did not try to bury my accent, that part of my cultural background. But that incident caused me to look harder and longer into my mirror.

After graduation I did make it to Indianapolis to work for a Black-owned weekly newspaper. I was the women’s editor and the only female reporter in the male-dominated newsroom. I still listened to that choice radio station. Eventually I landed in Cleveland where I spent 12 years getting to know the other women in the mirror. I worked for an organization that was female-led and culturally oriented. I was exposed to so much more of my African-American culture as well as African heritage. The founder and owner of the organization later admitted that she did not know how to take me at first. She said I was too light to be black. I was living on the west side of Cleveland in Parma where Black folks just did not live. And then I opened my mouth, there was that accent. She was not aware that African Americans lived in Southeast Kentucky. She was only seeing what the media chose to show.

As our local history has written, I found that many African-Americans living in Cleveland were born and raised in the hills of Southeast Kentucky, but they did everything they could to shed that suit and put on another, including dispensing of their accent. They blended in. They had been there too long and had no intention of ever returning to the mountains to live. But I could not change suits; if anything, I wanted to add different apparel to my wardrobe.

The mountains kept calling me home. As people told me, “You’re not Black enough for the city,” the mountains reminded me of my true home. I brought my new-found friends from the looking-glass with me; they were now part of me. I returned to the mountains like so many prodigal sons and daughters before me. I had come full circle.

These mountains no longer separate. These mountains no longer isolate. And yes, you can come home again.

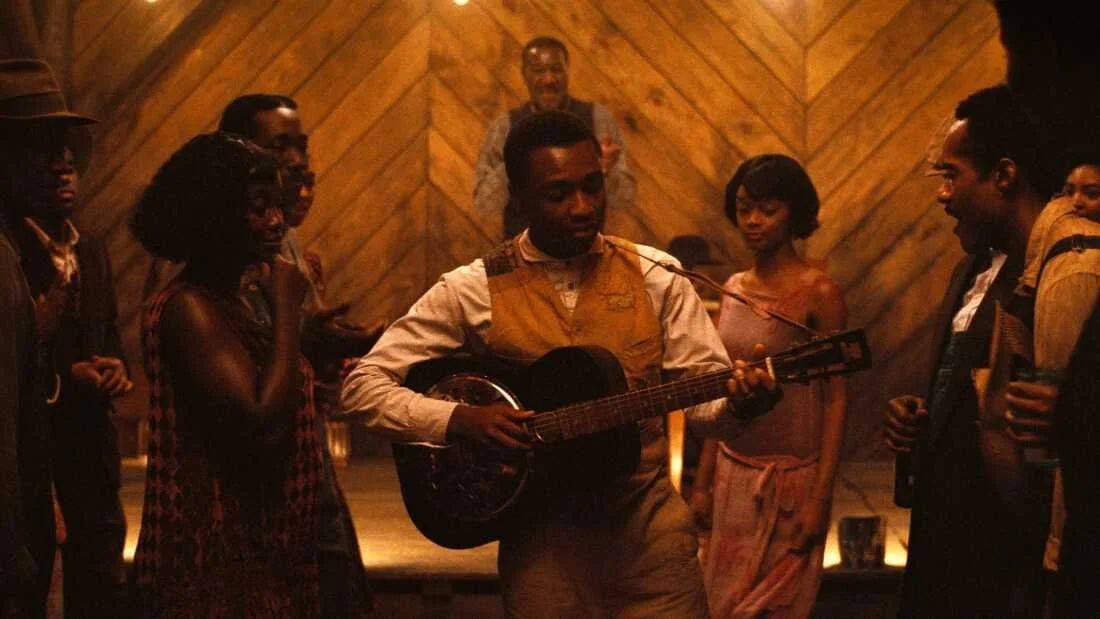

the blues that sprung from my roots

Growing up, I was often teased by my peers in school for liking blues. I did not mind though. I preferred the culture and history of the Blues instead of consuming dominant pop culture at the time. I had no true explanation as to why I felt the way I did about the Blues- I just did. Being a black man from the suburbs was my way of engaging with my environment. Some people say the Blues is something that comes to you, rather than you coming to it.

BY: KYLE THOMPSON

Growing up, I was often teased by my peers in school for liking blues. I did not mind though. I preferred the culture and history of the Blues instead of consuming dominant pop culture at the time. I had no true explanation as to why I felt the way I did about the Blues- I just did. Being a black man from the suburbs was my way of engaging with my environment. Some people say the Blues is something that comes to you, rather than you coming to it. Other people say you get the blues over a person you love. I think both are true, in a way, but no one has to live a hard life to feel the Blues. I got the blues yesterday when I dropped my sandwich on the ground.

There is something to this magnificent music that draws my ears in a way like no other. People always say that there is that one song that you hear, and when it grabs you, it holds you to your very core. I would say most, if not all blues music I came in contact with had that effect on me. One benefit of growing up in the age of the internet was that I had options to craft my individuality the way I saw fit. In this case, I dived deep into the blues, because it was always at my fingertips. The way I saw it, why would I only listen to what was popular when I could literally explore any genre I wanted? I listened to punk, afrobeat, hip hop, gospel, and classical music. In each of these genres, I found the blues. It was so interesting to me understanding how everyone’s favorite band loved and admired the blues so greatly, yet everyday people didn’t seem to care about blues.

I quickly learned that people’s perception of the Blues were heavily misguided. Some people thought it was just a black man strumming a guitar down south singing about whiskey and women. Other people reduced its complexity to being just a music that gave birth to Rock n’ Roll. The Blues in this narrative was an antiquated sonic form, its only purpose being a stepping stone to the development of rock and roll. Very few people were intentional in saying what it actually was though- an African American art form. I see the blues as a folkloric element to the Black experience that is passed down through generations- verbally or nonverbally. When I was a child growing up, my grandfather would sit in the back of his truck and listen to the radio. Oftentimes, I would tag along, and together we would spend afternoons sitting in his car listening to Blues music on the radio. I was much younger then, barely past four or five, however I knew that what I was experiencing was something special. I had no words to describe what that experience felt like until years later, when I came across a well-known painting called The Banjo Lesson by Henry Ossawa Tanner. In that image, I saw an aesthetic contextualizing the relationship with my own grandfather- a Black man passing down culture and folklore to a younger generation.

The blues has roots in field hollers, slave spirituals, and work songs meant to uplift the spirits of enslaved Africans brought to America. The pain, hardship, and inequality of slavery would naturally bring about a sound of music and cultural expression reflective of their environment. As slavery became replaced by the impact of Jim Crow, it became a new barrier to the success of the Black community to achieve and thrive. The blues acted as that healing, secular music that would be a form of release after a long day of work. Musicians would channel their experiences into singing about their lives, their experiences, and their emotions. I hear more than an aesthetically pleasing sound of music listening to blues. I heard the sounds of grandparents and their elders, recorded so long ago. I hear backyard fish fries, I hear trains bustling down the railroad, I hear cottonfields, I hear cars driving up and down the city highway, I hear community centers, I hear Thanksgiving, I hear Christmas with family, and I hear vestiges of African culture. The lives, slang, style, and morals were wrapped in the painful and profound. In a sense, when I listened to the blues, I was receiving this heritage that was apart of a larger narrative and experience. I found where I fit in my own culture, and in turn, where America and the world fit in with my expression.

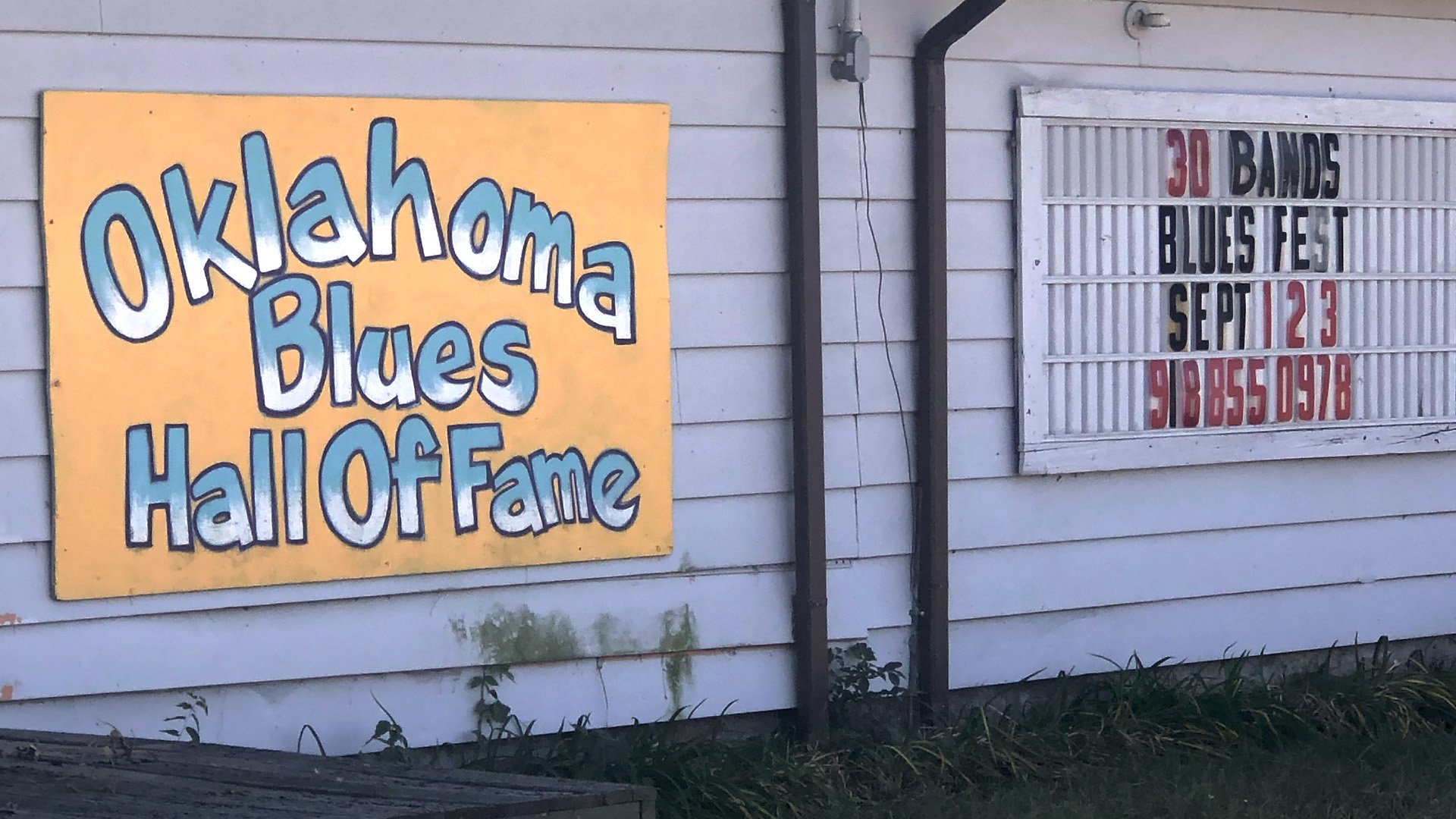

OKLAHOMA BLUES

Between the 1830s to 1850s, Native Americans of the Five Tribes were forcibly marched on the Trails of Tears from their homelands in the southeastern United States to the eastern part of modern Oklahoma, then called “Indian Territory.” With them, they brought their African American slaves. It must be understood that slavery in Indian Territory varied widely – ranging from resembling white cotton plantations, to commonly practicing intermarriage and allowing other extended freedoms. Linda Reese cites, “By the time of the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, the tribes' members owned approximately ten thousand slaves.”

BY: SELBY MINNER AND IRENE JOHNSON

“Da-dut – da-dah-duh – dah-de-dup!” My bass rang out across the crowd… I could hardly breathe! He had me starting the song as a solo – indeed the whole set! Up the steps he came, out from behind the stage and into the light, sporting a yellow ice cream suit and a big red guitar. The drums kicked in, the rest of the band, and then… Mr. Lowell Fulson hit the microphone and the place came alive: “TRAMP! You can call me that! But I’m a LOVER!” I was holding the bass line – one of the greatest bass lines. The man at the top of the West Coast blues was back home in Tulsa, and Juneteenth on Greenwood was rocking! D.C. was wearing “old shiny” – his green and red tux jacket – with his red guitar, Big Dave 'Bigfoot' Carr was in from Spencer, OK, with his sax, Jimmy Ellis on guitar and vocals, and Bob ‘Pacemaker’ Newham on traps. It was 1989 and Lowell Fulson was at home to be inducted into the Oklahoma Jazz Hall of Fame. He later said he would come back to play the Traditions Festival in Oklahoma City in the fall, but only if he had the same backup band! Such an honor to play with an Oklahoma legend!

Oklahoma’s unique history and heritage provided fertile ground to grow its particular blues sound. Before we can dive into the blues, though, we need to travel back to Oklahoma before it gained statehood in 1907. I call it the wild west – where anything could happen.

Between the 1830s to 1850s, Native Americans of the Five Tribes were forcibly marched on the Trails of Tears from their homelands in the southeastern United States to the eastern part of modern Oklahoma, then called “Indian Territory.” With them, they brought their African American slaves. It must be understood that slavery in Indian Territory varied widely – ranging from resembling white cotton plantations, to commonly practicing intermarriage and allowing other extended freedoms. Linda Reese cites, “By the time of the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, the tribes' members owned approximately ten thousand slaves.”1

The Civil War was fought from 1861 to 1865. Dr. Hugh W. Foley, Jr. writes, “The Civil War’s presence in Indian Territory is directly related to Black pride in the area, as the Battle of Honey Springs, fought July 17, 1863, witnessed the first pitched combat by uniformed African American troops, the First Kansas Colored Volunteer Infantry Regiment, who fought alongside Anglo and American Indian troops. Fought just north of what is now Rentiesville, the battle has been called the ‘Gettysburg of the West.’”2 It was a running battle there at Honey Springs – some of it actually took place on our land where my husband D.C. Minner and I established the Down Home Blues Club (which hosts the Rentiesville Dusk ‘Til Dawn Blues Festival, the Oklahoma Blues Hall of Fame and the D.C. Minner Rentiesville Museum). Some of the soldiers from that battle went on to help found Rentiesville.

The end of the Civil War sparked big transitions for the “Twin Territories” of Indian Territory and Oklahoma Territory. Reese explains, “The government insisted on the abolition of slavery and the incorporation of the Freedmen [former slaves] into their respective tribal groups with full citizenship rights. All of the Indian nations were willing to end slavery, but citizenship rights conferred access to land and tribal monies as well as political power.”1 Despite tribal attempts to maintain control of their land and tribal monies through the U.S. courts, Freedmen were ultimately given full rights. The Dawes Act, which was the federal government’s way of breaking up commonly held tribal land into individual allotments, granted Freedmen “approximately two million acres of property, the largest transfer of land wealth to Black people in the history of the United States.”3

Reese goes on, “Freedmen from adjoining states had slipped into the territory for years, intermarrying with their Black Indian counterparts or homesteading illegally, but now the opening of Indian lands to non-Indian settlement gained momentum and brought hundreds of migrants both Black and white.”1 Oklahoma, considered the “First Stop Out of the South,” was indeed the “promised land” for about a 30-year window, offering land allotments and opportunity. It was close enough to the South to travel by wagon, folks could grow the same crops, and since it was not yet a state, there were no oppressive Jim Crow laws.

Freedmen often decided to settle together. It was at this point that the idea for all-Black towns developed. Larry O’Dell explains, “They created cohesive, prosperous farming communities that could support businesses, schools and churches, eventually forming towns. Entrepreneurs in these communities started every imaginable kind of business, including newspapers, and advertised throughout the South for settlers.”4 I’ve heard it said, the word was “tremendous opportunity, come help us do this… don’t come lazy and don’t come broke!”

The upshot of this opportunity was that more than 50 all-Black towns were established. These towns emphasized education, self-governance, strong churches and communities, and were held together by the economic security of their agricultural land. They believed that education was the key to a better future; the schools were strict and people graduated high school. My husband, Rentiesville native and bluesman D.C. Minner used to say, “If I did not get my lesson, I got a whoopin’ from the teacher. On my way home, my friend’s mom would give me a whoopin’, and when I got down here to the house Mama [his grandmother who raised him, Miss Lura] would give me a whoopin’, and she didn’t even want to know what I did wrong! If I got it from the others, she just had one coming too!”

Here’s where we can pick up on the music coming out of Oklahoma. Foley explains that the opportunities available during this time crafted the music legacy of the region; “Access to music lessons, instruments and mentors help explain why more African American musicians from Oklahoma developed the advanced musical skills necessary to evolve into jazz artists… As social and economic conditions changed for the state's African Americans by the 1920s and 1930s, more musicians born during that time period evolved into traditional, guitar-based practitioners of the blues.”5 Musicians who could read jazz charts went east and worked in almost every major jazz ensemble out of New York.

The jazz and blues players in Oklahoma were, in many ways, one community, particularly in major cities, such as Oklahoma City, Tulsa and Muskogee. In an interview with Bill Wax on Sirius XM’s B.B. King Bluesville, B.B. King said, “Jazz players say you can’t play good jazz unless you know the blues.” And D.C. said, “The R&B and blues bands here in the ‘50s and ‘60s all started their blues sets with an hour of instrumental jazz, so people could come in and get comfortable, and so the horn players could work out and do solos before they had to settle down to ‘blow parts’ – be rhythm players, essentially.” So, you see, there’s a blurred line there between jazz and blues here.

Given its history, plus the connection to Texas and the West Coast (you can drive to California without scaling the Rocky Mountains; there is a lot of work out there for musicians), I call Oklahoma – and Texas – “the cradle of the West Coast Blues.” Blues from Oklahoma is unique. Its sound includes horn sections, it’s a little smoother and the players dress – they consider themselves a little more “city” or “slicker.”

An integral part of Oklahoma’s blues sound developed with the Texas-Oklahoma “Hot Box” guitar style. Unlike the slide playing or finger picking styles from the Piedmont and Mississippi-Chicago sounds, the “Hot Box” guitar style is a single-note lead style that has a great local lineage that eventually crossed over to rock ‘n roll. Starting around 1900, players of this style include Blind Lemon Jefferson (possibly the earliest to record this style), jazz innovator Charlie Christian (the first to put electric guitar solos into jazz), T-Bone Walker, Freddie King, Stevie Ray Vaughan, B.B. King to Eric Clapton and beyond. The Hot Box single-note lead style is the style of most American rock ‘n roll to this day! B.B. King said in another Bill Wax interview, “I am from Mississippi, but my fingers are too lazy to play Mississippi style, I play Texas!”

There is no “music industry” per se in Oklahoma like there is in Nashville, Austin or Chicago; most people who play professionally work out of state. But since there are lots of juke joints in these towns – five in Rentiesville alone – there’s still a lot of music! Oklahoma has produced numerous great musicians and I’d love to tell about each and every one, but I’ll have to settle for highlighting just a few, with the help of Hugh W. Foley, Jr.’s “Blues” for the Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture.5

Hart Wand of Oklahoma City actually published “Dallas Blues,” the first 12-bar blues on sheet music, in March of 1912 – the same year W.C. Handy published “Memphis Blues,” widely considered the first blues song.

There were several territorial bands that played a circuit in the early 1900s across Oklahoma, Texas, Arkansas, Kansas, Missouri and Nebraska. The best of these bands was the Oklahoma City Blue Devils, which later became the core of the Count Basie Band out of Kansas City. Truly the bluesiest of all the touring jazz bands, I would say.

Jay McShann supplemented his passion for the blues with what he learned in the Manual Training High School band of Muskogee, OK, and went on to lead one of the great blues-based big bands of the 1930s and 1940s out of Kansas City. His "Confessin' the Blues" was one of the biggest selling records for a Black artist in the early ‘40s.5

Joe "The Honeydripper" Liggins charted a number of singles, including "The Honeydripper" and "Pink Champagne,” during the late 1940s and early 1950s with his streamlined rhythm and blues. His brother, Jimmy Liggins, led an amplified R&B group that preluded rock ‘n roll with hits like "Cadillac Boogie," "Saturday Night Boogie Man," "Drunk" and later, his now-classic blues song "I Ain't Drunk." Bandleader, drummer and songwriter Roy Milton’s “jump blues” served as a precursor to rock ‘n roll.5

Jimmy “Chank” Nolen was another of Oklahoma's important blues guitarists. Credited for inventing the "chicken scratch" guitar style, Nolen is considered the “father of funk guitar.”5 The chord on the guitar is played in such a way that is very percussive, like a drum beat. Since it makes guitar rhythms very danceable, James Brown picked Nolen up to record as primary guitarist on several major hits.

Gospel and soul-blues singer Ted Taylor experienced success with his falsetto-driven voice in the 1950s- ‘70s. Guitarist Wayne Bennett worked with Elmore James, Jimmy Reed, Otis Spann, Otis Rush and Bobby "Blue" Bland. Verbie Gene "Flash" Terry recorded the hit, "Her Name is Lou,” and later toured with T-Bone Walker, Bobby "Blue" Band, Floyd Dixon and others.5

Guitarist Jesse Ed Davis, a Native American with Comanche, Kiowa and Muscogee heritage, toured with Conway Twitty in the early ‘60s before moving to California and joining Taj Mahal. Davis’ “reputation led to sessions for Leon Russell, Jackson Browne, Eric Clapton, John Lennon, Ringo Starr and Captain Beefheart, as well as four of [his] own solo albums.”5

Larry Johnson and the New Breed (with D.C. Minner on bass) were the house band at the Bryant Center in Oklahoma City, playing several nights a week and backing up touring headliners like Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley for almost 10 years.

Lowell Fulson is probably Oklahoma’s most widely recognized blues guitar star. “By adding a horn section in the mode of swing bands to his electric blues lineup, Fulson created what is typically called the ‘uptown blues’ sound, which B. B. King made famous. Fulson's huge 1950 R&B hit, ‘Everyday I Have the Blues,’ became King's theme song”5 – surfacing the Texas-Oklahoma “Hot Box” guitar sound once again to evolve into what we know as the popular blues style!

Foley concludes, “Anglo-American blues men who emerged primarily from the Tulsa scene in the 1960s include pianist Leon Russell and guitarists J. J. Cale and Elvin Bishop.”5

I could keep going – multi-award-winning Watermelon Slim, extraordinary blues belter Dorothy “Miss Blues” Ellis, Jimmy Rushing of the Blue Devils and Count Basie's Orchestra, and so many more – but I’ll end my abridged round-up with my late husband, blues guitarist D.C. Minner.

D.C. was raised in Rentiesville by his grandmother, who owned and operated a grocery store/juke joint called the Cozy Corner in the 1940s- ‘60s. Here, he was exposed to all the music coming through. He toured, playing with Larry Johnson and the New Breed, Lowell Fulson, Chuck Berry, Freddie King, Bo Diddley, Jimmy Reed and Eddie Floyd before starting our own band, Blues on the Move. In 1988, we got tired of the road and moved from the California Bay Area back to Rentiesville, and reopened his grandmother’s old juke joint as the Down Home Blues Club.

In 1989, we established the Blues in the Schools program through the Oklahoma State Arts Council. In 1991, we started the Rentiesville Dusk 'Til Dawn Blues Festival to feature local and regional blues artists, and it has become the longest running blues festival in the state and renowned nationwide. It’s here, where I also still run our other projects – the Oklahoma Blues Hall of Fame and the D.C. Minner Rentiesville Museum.

In 1999, we received the Keeping the Blues Alive Award from The Blues Foundation for our efforts and contribution to music education and blues history. D.C. went on to being inducted into seven Halls of Fame, including the Oklahoma Jazz Hall of Fame in 1999 and the Oklahoma Music Hall of Fame in 2003.

D.C believed, “This is one of the few places where this history is still left,” and I work diligently and joyfully to keep the blues – and this rich history – preserved and alive in Oklahoma.