The Copper-Colored Race

Why aren’t Black Indians part of black history month

Written By: Lamont Jack Pearley

Black History Month, also known as African American History Month was the brainchild of Carter G. Woodson an author, journalist, and historian, in 1925. Looking to bring attention to the contributions of African Americans in a Non- Black dominated American system, Woodson launched the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (ASNLH), which quickly lead to the conception and bringing forth of Negro History Week in 1926. Galvanizing the energies and excitement of black teachers, activists, and organizations, as well as white progressives and philanthropists, Black History Month in the course of 50 years grew from a one-week celebration to a nationwide week celebration, all the way to a full month extravaganza encouraged by President Gerald R. Ford in 1976. Since then it’s been a call for politicians to connect with the African American Community. Used to make black students of all ages and grade levels feel included within the school system, and presented as the one month out of the year to celebrate, honor and study black America. It’s a time where the nation reflects on the one-time battered slave who by some means learned to read and swindle their way into the good grace of the elite white power structure. It’s also the month every ethnicity and nationality remembers Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, Harriet Tubman, and the few other documented black hero’s that made it into the mainstream textbooks. However, there is a group of black folk, that truly would be considered Black American, or even American Black that is rarely mentioned in the celebration of Black History Month. They are called “The Copper Colored People.” According to the American Dictionary of English, also referred to as Webster’s Dictionary 1828, the “Native American,” also called “Indians” were as described - “AMER'ICAN, noun A native of America; originally applied to the aboriginals, or copper-colored races, found here by the Europeans; but now applied to the descendants of Europeans born in America.” The latter part of that definition is telling, however, we’re discussing the copper-colored people.

So who are the copper-colored people, and why are they important? There are documentaries and literature that makes the claim “Black Indians” are the offsprings of Africans and Natives intermingling, however, there is evidence that the term “copper-colored” is equivalent to “negro,” or “black,” as well as “brown,” and that these “copper-colored,” or “black people” are the original occupants of this land, hence the definition above. For me, knowing that my family story so far begins in Mississippi and Louisiana, as well as having confirmation that my mothers' parents are of Choctaw bloodline, inspires me to raise the question of Black Indians partaking in the annual Black History Month festivities. It also raises the question of who the Blues People of the delta are. Furthermore, being a dark skin man, my mother a dark skin woman, and my grandfather likewise of dark complexion, I still have to ask, why aren’t Black Indians more present in this celebration? Or, are they? Before we can address that, I believe a more pivotal conflict would be the description of Black Indians. Again, if we take the Webster’s Dictionary of 1828 as fact, it clearly states who is and how the aboriginal of this land looked, but when you read and research documents of academics and historians, Black Indians are described as mixed, or, essentially African converts. November 30, 2010, NPR’s the show "Tell Me More” conducted a month-long series that observed National Native American Heritage Month. This particular episode struck me based on its description; “Tell Me More’ concludes its observance of National Native American Heritage Month with a look at the struggle of some African Americans for acceptance by those whom they consider kin.” Usually, I love to listen to NPR’s audio podcasts, but this time I needed to read the transcripts. I had to see in black & white what were the thoughts, beliefs and supposed facts presented by the host and guests of this show.

The show host Michel Martin spoke with guests William Katz, author of Black Indians: A Hidden Heritage, and Shonda Buchanan, an English professor, who is of North Carolina and Mississippi Choctaw Indian ancestry. The show description further explained that they looked to explore shared black and Native American heritage. William Katz’s book, Black Indians: A Hidden Heritage raises the case that runaway African slaves in America's initial place of asylum, so to speak, was to flee to Native Reservations. There, the African slave, (male or female) would be welcomed and build relationships that lead to interracial marriages and acceptance by the tribes. This is how he describes the origins of the Black Indians or the connection between African Americans with Natives. The interview begins like this:

MARTIN: So, Mr. Katz, will you start with us and just tell us how the relationship between African-Americans and Native Americans began?

Mr. KATZ: Well, it began with the earliest colonial period. Soon after Columbus arrived, Africans were brought in. And so you have a pattern of Native Americans taking in African-Americans and the two people mixing and forming a kind of united front against the forces that were bringing slavery and colonialism to the Americas. So this has a long, long history.

This conversation sets up a false narrative that Indians weren’t black, to begin with. The language used in the description of the people infers the Indian and the African having different hues. The use of political terms like African American mixing with Native Indians gives a sense that the Natives weren’t black until they began to mix with Africans and their descendants. The way it’s presented is false, however, the Natives indeed helped those in bondage.

Some would question why would it be important to make this distinction between political names, or even the actual color of the original American. I’d counter by explaining, if you were always told Indians looked like their portrayal in movies, and just excepted that without questioning it, then you would never find a red flag in Mr. Katz's description of the “Black Indian.” Nor would you be so inclined to investigate if there and what was the relationship between “African Americans” and “Natives.” Furthermore, which is the elephant in the room, one wouldn’t venture to investigate why most people who categorize themselves as African American are in fact descendants of Black Indians. To honestly and earnestly celebrate Black History Month, we should know, or at least want to know who a great percentage of Black people are, let alone where they descend.

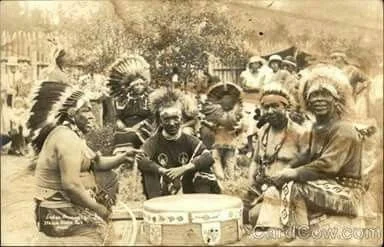

Many documented facts back up my claim. One, you can ask Black Indians, two, you can look up William Byrd. William Byrd was a white man of the Virginia Colony. He and others of the Colonial Council and the Commonwealth of Virginia committed colonial encroachment, economic suffrage and violations of their treaty’s with the Natives. If you read his report from his visit to the Cheroenhaka-Nottoway Indian Tribe of Southampton County, Virginia, in 1728 called the William Byrd Papers, you’d find some interesting facts. He states, “the young men danced to the beat of a gourd drum, stretched tight with a skin - the women wore Blue and Red Match Coats with their hair braided with Blue and White beads.” He also states about the women he sees, “these dark angels will make exceptional wives for the English planters. Their dark skin would bleach out in two generations.” In an interview on WHRO Public Media program called ‘Another View” Chief Walt “Red Hawk” Brown of the Cheroenhaka-Nottoway Indian Tribe states, “First Americans was a rich brown people! They were mahogany in color.”

Even with that being said it still may be a far stretch to say majority, if not all African Americans are descendants of Black Indians, and not African converts or the children of Africans and Natives mixing. That’s where Walter Ashby Plecker comes into play. Plecker ran Virginia’s Bureau of Vital Statistics, which was established in 1912. Plecker, a practicing eugenicist, changed the birth certificates, marriage licenses and other documents of Black Indians. He even wrote letters to census takers giving them instructions on how to categorize Black Indians. His Racial Integrity act of 1924 further destroyed the identity of the Black Indian, by changing the categories on documents to simply “White and Black.” At this point, Black Indians in this region went from “Colored” to “Black,” which we know was followed by Afro- American and then, African American.

Again, those are just a couple of examples. This article is the first in a series of articles on the Black Indian. So as we celebrate Black History Month, I would encourage you all to open your mind, question almost everything, and ask yourself, “Who are the Blues People?” Because with this research, as well as tracing back to the “Entire Delta Region,” one should begin to revisit, re-read and question a lot of the documentation that’s been presented and archived about the Blues People.