COLONIALISM & INSTITUTIONS

White Colonial Ideologies and the Institutionalization of Power

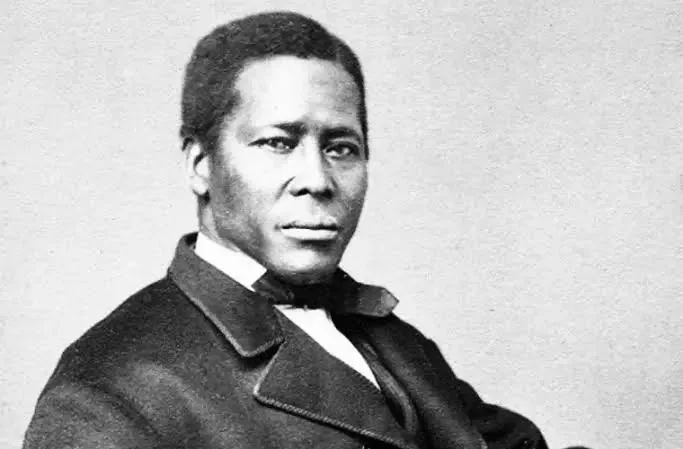

William Still: Black Ethnographer of the Underground

William Still wasn’t just recording history. He was practicing a distinctly Black ethnographic methodology grounded in survival, storytelling, and freedom.

By Lamont Jack Pearley

“More than a conductor on the Underground Railroad or the secretary of an historically Black organization, William Still was an early Black ethnographer—archiving memory, testimony, and survival from within the movement itself.”

When we speak the names of our ancestors who laid the groundwork for what we now call Black folklore and fieldwork, it’s crucial that we include William Still.

Many recognize Still as the “Father of the Underground Railroad,” the free Black man in Philadelphia who helped hundreds of freedom seekers escape bondage. That legacy is powerful, and it’s true. However, what often goes unspoken is that Still, through his 1872 book The Underground Railroad, wasn’t just a freedom fighter; he was a fieldworker, a documentarian, and a cultural preservationist. Essentially, Still, like Charlotte Forten Grimkè (whom Still comes out of her family’s camp) was an ethnographer, utilizing folkloristic methods. He was doing the work we now identify as ethnography and Black folkloristics long before those terms were formalized or acknowledged within the academy. Even before Childs, Newells, Brinton, and Boas thought to utilize a Euro lens at what they called “advocating for the respect and understanding of diverse human cultures and traditions..”

Still’s work represents one of the earliest examples of community-rooted field documentation, carried out not from a distance, but from within the very movement it preserved. He created a collection of what is referred to as primary source material.

A Fieldworker in the Fight

Still didn’t interview his subjects years later in comfort. He sat with them immediately upon arrival, sometimes the same day they escaped slavery. He took down their names, places of origin, escape routes, kinfolk left behind, and in many cases, their own personal philosophies. These weren’t secondhand reports or reimagined tales; this was real-time testimony, captured from within the movement itself.

That makes William Still a participant observer, an embedded witness, not just to the facts of escape, but to the internal, spiritual, and familial world of the people in motion. He was practicing what we today call field ethnography, gathering firsthand accounts, contextual details, vernacular language, and deeply cultural expressions from those who lived through it as he led them to their destinations.

He wasn’t collecting data for the sake of scholarship. He was preserving Black memory, so it couldn’t be erased, distorted, or forgotten. He had purpose!

The Archive as Resistance

What distinguishes Still’s work from many other abolitionist documents of the time is that he prioritized Black voice and agency. He didn’t translate their stories into respectable terms for white audiences. He didn’t flatten or edit their words to fit a political script. He let the people speak. He recorded their truths on their own terms. A methodology championed by ethnomusicologists and folklorists currently, as most have come to realize the initial aesthetics and practices of the field and discipline have been racist, sexist, and replete with class warfare.

That’s not just abolitionist work, it’s counter-archival work. Counterintuitively, it is archiving through the lens of what is significant to Black Americans and Afro-Indigenous framing—not archiving and collecting based on outside understanding of what would constitute communal black memory to move the tribes and peoples forward. Still built a repository of Black narrative ownership, one that resisted erasure and claimed the right to document life, pain, joy, and freedom in our own voices. Still gave us the blueprint of black documentation, repository, and archiving for the field ethnographic interviews conducted by insiders. Insiders, in the sense of Black voices documenting Black voices.

Still’s archive includes spiritual beliefs, coded songs, family stories, resistance strategies, and moral convictions. It mirrors today’s folkloristic methods, centered on lived experience, oral tradition, and community truth-telling. Not only did he work as a public folklorist, but he also applied early methods of ethnomusicology, as Still documented the engagement of the folks he interviewed with their music and sonic expression.

A Method Rooted in Culture

From a folklorist’s standpoint, Still’s book is filled with the elements we seek when we enter the field: kinship structures, regional knowledge, spiritual worldview, vernacular storytelling, and historical context embedded in everyday life. He didn’t just collect who went where; he preserved how they thought, what they believed, and why they moved the way they did.

This kind of documentation is what I call Black cultural fieldwork, not just recording for the sake of records, but preserving for continuity, justice, and cultural memory. Essentially, this is the precursor to the Blues Narrative. Still’s methodology was informed not by theory, but by responsibility. A responsibility that lives in ethics! Still didn’t have to develop ethics to conduct his work; his work was born out of the sensitivity and treatment of his people. Out of a cotastraphe, out of war, natural disaster, ultimately, out of prisoners of war named slaves. He understood the weight of the moment and responded with care.

His work is a model of Blues People Preservation: rooted in the community, accountable to the community, and crafted to safeguard the legacy of Black life as told by those who lived it.

What This Means for Us

As a practicing folklorist, traditional Bluesman, and cultural preservationist, I often turn back to Still, not just for his content, but for his approach. He reminds us that fieldwork is not neutral. It’s a choice. And when done right, it’s an act of love and resistance.

In a time when Black stories are still commodified or misrepresented, Still’s work teaches us that to document our people means to honor them, to believe them, and to trust their voice over interpretation. There is no talk of ethics or this idea of objectivity. Still approaches as an applied ethnomusicologist and applied Folklorist,

Still’s legacy lives in every oral history I collect, every field recording I make, every sacred story I preserve. His pen was a tool of liberation. His book is a cultural lifeline.

We Are Still Building

At The African American Folklorist, our mission aligns with Still’s foundational work. We uplift and amplify Black voices, not as subjects but as narrators, theorists, and keepers of knowledge. We build our archives not only to preserve the past, but to affirm the present and shape the future.

William Still wasn’t just recording history. He was practicing a distinctly Black ethnographic methodology grounded in survival, storytelling, and freedom. It’s time we place him alongside our greatest cultural scholars, not just for what he did, but for how he did it.

And so, we carry the torch, not just of freedom, but of Black fieldwork that listens, documents, and preserves with purpose.

Lamont Jack Pearley is a traditional Blues artist, public folklorist, and founder of the Jack Dappa Blues Heritage Preservation Foundation and The African American Folklorist Magazine. His work centers the voice, memory, and lived experience of the Black Blues People through research, music, oral history, and cultural fieldwork.

“The Archive Is Alive: We Are What They Imagined

In the Black folk tradition, we say the ancestors are always speaking. You just have to listen. The African American Folklorist was born out of that deep listening. It is not simply a magazine, platform, or project—it is a response. A call and response, to be exact. We are answering the calls of those who came before, affirming their intellectual labor, carrying forward their cultural vision, and transforming their blueprints into living, breathing work.

Written By: Lamont Jack Pearley

How Foundational Black Thinkers Confirm and Call for the Work of The African American Folklorist

The African American Folklorist platform is a contemporary manifestation of the intellectual, cultural, and spiritual legacy left by Black scholars, activists, cultural workers, and theorists. Many of these individuals called for or modeled the very practices now embedded in the African American Folklorist’s mission—oral history collection, community-based publishing, cultural repatriation, and the interpretation of Black life through the lens of folklore, Blues, and lived experience.

The Archive Is Alive: We Are What They Imagined — Confirmed by the Ancestors, The African American Folklorist as Continuum

In the Black folk tradition, we say the ancestors are always speaking. You just have to listen. The African American Folklorist was born out of that deep listening. It is not simply a magazine, platform, or project—it is a response. A call and response, to be exact. We are answering the calls of those who came before, affirming their intellectual labor, carrying forward their cultural vision, and transforming their blueprints into living, breathing work. This essay traces how foundational Black thinkers, scholars, and cultural workers have not only confirmed our mission but, in many ways, demanded it. This is a chorus of lineage, and we are its next verse.

W.E.B. Du Bois laid the foundation with his insistence on documenting Black life through a lens that recognized its soul, its sorrow songs, and its sociological richness. In The Souls of Black Folk, and even more so in his Georgia fieldwork, Du Bois called for what we now recognize as folklore work rooted in lived Black experience. His vision of cultural science from within is a direct ancestor to the Blues Narrative we carry forward today.

Arturo Schomburg reminded us that the Black archive is not optional—it is essential. By insisting on the collection and preservation of Black cultural materials, Schomburg emphasized that self-representation is historical reclamation. The African American Folklorist, in all its formats—print, digital, audio, and live broadcast—embodies that ethos. We are not collecting for curiosity; we are archiving for sovereignty.

Carter G. Woodson democratized the discipline. By founding Negro History Week and writing for everyday people, he validated community-led knowledge production. Our platform exists in that same spirit, guided by the belief that tradition bearers, community scholars, and culture keepers are theorists in their own right. Like Woodson, we reject the ivory tower as the sole house of knowledge.

Anna Julia Cooper ensured that Black women’s voices were never footnotes. She spoke from the intersection before it was named as such, claiming space for Black women as central agents in cultural theory and preservation. Our "Women's Folklife" series and the Black Blues Women project echo her call.

John Wesley Work III quietly modeled what we now do loudly—he collected, documented, and dignified Black music as a folklorist. His fieldwork on spirituals and Blues set the stage for the Blues Ecology framework we now build upon: music as memory, landscape, and liberation.

LeRoi Jones, later Amiri Baraka, did not merely describe Black music; he politicized it. Blues People is a map of our musical epistemology. Through Baraka, we understand that every moan, shout, and lyric is a historical document. Our podcast episodes, narrative essays, and musical analyses stand on his shoulders.

James Cone gave us the theology. He revealed that the spirituals and the Blues are not oppositional but deeply entwined expressions of Black theology. When we speak of Slave Seculars as sacred testimony, we are echoing Cone’s liberation theology with a folklorist's ear.

John Henrik Clarke demanded that Black people write, teach, and theorize their own history. He modeled intellectual sovereignty, which is the bedrock of our editorial and fieldwork ethos. Our contributors are not just writers—they are cultural witnesses.

Michael Gomez traced the continuity from Africa to the American South, from country marks to communal memory. His diasporic methodology informs our cultural documentation of Blues people, African survivals, and folk traditions that span generations.

bell hooks, in Black Looks and beyond, urged us to view Black cultural production as resistance and as love. She reminded us that theory lives in the everyday. Our magazine and platform bring theory to the porch, the juke joint, the sanctuary, and the street.

The Negro Women’s Club Movement were grassroots folklorists before the term became academic. They held pageants, collected oral histories, and preserved foodways. We follow in their tradition by uplifting vernacular knowledge and celebrating communal care as cultural labor.

Charlotte Forten Grimké documented the everyday life of Black folk during Reconstruction—a proto-ethnographer who reminds us that journaling, witnessing, and testifying are tools of survival and scholarship. Our fieldnotes echo her pen.

Alexander Crummell believed in Black moral uplift and nationalism. His call for sovereignty undergirds our push for Black cultural self-determination through folklore.

Chancellor Williams, in The Destruction of Black Civilization, offered historical repair through people’s history. That same repair is what we aim to enact in our heritage and repatriation work.

Nathaniel Norment Jr. advocated for Black rhetorical traditions as identity formation. We continue this by affirming storytelling, performance, and vernacular speech as theoretical frameworks.

Anthony Benezet, though not Black, represents early allyship in educational justice. His presence reminds us that solidarity is a practice, not a slogan.

James Forten and his family legacy supported abolition and Black education through print culture. We are his digital descendants, publishing for liberation.

Kimberly R. Norton represents our scholarly present and future. Her work in Black cultural heritage and folklore bridges the academic and the communal, much like our mission.

We are the living archive. We are the embodied return. The African American Folklorist is not just a publication; it is confirmation. Confirmation that the ancestors dreamed us. That they theorized this work. That they laid the foundation so we could build. And now, build we must.

Copyrights 2025

The idea that major record labels will be devastated by the wave of artists reclaiming their copyrights is almost laughable, especially when considering what these labels currently own and control.

Written By:

Allen Johnston

Music Specialist

Big Joe Turner

The idea that major record labels will be devastated by the wave of artists reclaiming their

copyrights is almost laughable, especially when considering what these labels currently own

and control.

Major record companies have long relied on their back catalog as a built-in revenue stream.

Sales of CDs, digital streams, vinyl, and live performance recordings continue to sustain them

while revenue from new artists remains unpredictable. Over the decades, these corporations

have strategically structured the industry in their favor.

During the 1980s, major labels executed a plan that dismantled independent Black and White

retailers while securing dominance over distribution. They introduced the SoundScan system,

offering free computers to independent store owners and coalitions. This initiative gave labels

direct access to sales data, allowing them to pinpoint which catalog titles were consistent

sellers. With this knowledge, they could optimize manufacturing costs while maximizing profits.

Since they owned the copyrights, they essentially paid themselves through mechanical,

synchronization, and performance publishing rights.Recording contracts from that era—and even before—ensured that major labels retained nearlyall revenue streams from copyrights. Artists were left with only a fraction of publishing revenue, limited performance royalties, and sometimes a cut of merchandising. PA (musical composition) and SR (sound recording) copyrights for nearly every hit song before 1984 remain under the ownership or control of a major label or one of its affiliates. For instance, Sony Music might control the SR copyright of a song, hold at least 50% of the PA copyright through contractual agreements, and place the composition within its wholly owned publishing division. This setup allowed money to circulate internally, with one corporate division paying another. Additionally, many artists had taken advances against royalties, leading to labels claiming ownership over original songwriter shares as well.

Artists affected by these agreements include, but are not limited to: Aretha Franklin, Marvin Gaye, Otis Redding, Ray Charles, Chuck Berry, James Brown, Clyde McPhatter & The Drifters, Big Joe Turner, The Temptations, Little Richard, Wilson Pickett, Fats Domino, The Dominoes, Sly & The Family Stone, Lloyd Price, Martha & The Vandellas, Parliament-Funkadelic, The Four Tops, The Isley Brothers, Jackie Wilson, Smokey Robinson & The Miracles, Kool & The Gang, The Supremes, Frankie Lymon & The Teenagers, Earth, Wind & Fire, and many more.

Even in the worst-case scenario, where some artists reclaim their rights, major labels will simply renegotiate with savvy copyright owners who have financial leverage. For everyone else, it will remain business as usual—offering advances in exchange for new contracts.

These catalogs retain immense value in the digital age, particularly in streaming, film and commercial licensing, and corporate partnerships. With their industry connections, financial muscle, and technological infrastructure, major labels remain well-positioned to continue profiting from these assets.

Black Business in Colonial America

As enslaved Africans gained their freedom in colonial America, they used the labor activities learned in slavery to start a new life. Across the cities and towns of this nation, free Blacks set up agribusinesses and took up as bricklayers, gunsmiths, shoemakers, nurses and innkeepers to form the initial steps of the Black business community.

By Karleton Thomas

As enslaved Africans gained their freedom in colonial America, they used the labor activities

learned in slavery to start a new life. Across the cities and towns of this nation, free Blacks set

up agribusinesses. They took up as bricklayers, gunsmiths, shoemakers, nurses, and innkeepers

to form the initial steps of the Black business community. Collectivism underlined the economic

activity of free Blacks in colonial America as they worked to establish independence in an

outwardly racist society successfully.

Those days are long gone, and blatantly racist laws, such as those barring credit to free Blacks,

no longer sit on the books of American cities. By comparison, the discriminatory laws of today

hold little weight when viewed next to laws in place during colonial America. Few, if any, Black

businesses of that time were allowed to grow outside of the community, but colonial-era Black

businessmen thrived when compared to those of today.

Many arguments have been made regarding the decline of the Black business community -

integration, angry white mobs, racist laws, etc. Though all contributing factors, none can fully

explain the demise of the Black business community. As markets opened up and Blacks were

able to walk through doors closed to previous generations, one would expect burgeoning Black

business metropolises to follow, but despite our best efforts, that never happened.

Today, most Black businesses fail within four years. For all the businesses being started by

Black entrepreneurs today, 87% will gross less than $15,000. Most can be categorized as

lifestyle businesses - entities run by its founder for the benefit of its founder. That’s a hard sell in

a community but despite this, the age of individualism looms on. It wasn’t the angry mobs or

racist laws that first slowed and then stalled progress, it was the varying motivations developed

amongst the Black community. Now, instead of a few options, Blacks were able to chart

individual pathways designed for their sole benefit. This produced outstanding, singular results,

but for many Black entrepreneurs the lack of community has proven to be an insurmountable

obstacle.

Our formerly enslaved, African ancestors practiced collectivism because pulling together to

ensure a chance at survival. Collectivism does not make much sense today but the principals

live on in cooperative business practices. A cooperative business model is one that responds to

the needs of all stakeholders; employees, customers, suppliers, the local community, the

environment and future generations, as well as investors. The adoption of the cooperative

business model as the framework for current and future Black business communities presents

two huge benefits: the recirculation of Black dollars and low unemployment.

The Black dollar and its effect or lack thereof has been well documented across academic

journals. At one point, it was reported the average lifespan of the Black dollar in the Black

community was six hours compared to 28 in Asian communities. That fact was proven to be

false but when the majority of businesses in Black communities are owned by individuals who

do not live or hire from that community - the truth is not far away. It is safe to assume that over

$.50 of every dollar spent leaves the community.

When a business in the Black community is owned by someone who lives and hires from the

community - we all benefit. Cooperative business models present a number of workforce

development opportunities for free Blacks who have been denied entry to the traditional job

market. As more cooperatives are formed, unemployment in those areas will dramatically

decrease, so will crime, drug use, and dependence on government programs. Grocery stores

wholly owned by the community can employ 100’s of employees with an invested interest in that

venture's success. They would live and work in the same area - tending to and protecting their

future.

Buffalo Soldier Project, San Angelo Texas, and Black History

In this episode of the African American Folklorist, I speak with Sherley Spears, NAACP Unit 6219 President, President of the National Historic Landmark Fort Concho, and founder of the Buffalo Soldier Project. The National Historic Landmark Fort Concho Museum preserves the structures and archeological site features for pride and educational purposes, serving the San Angelo, Texas community.

By Lamont Jack Pearley

In this episode of the African American Folklorist, I speak with Sherley Spears, NAACP Unit 6219 President, Vice President of the National Historic Landmark Fort Concho Museum Board, and founder of the Buffalo Soldier Project. The National Historic Landmark Fort Concho Museum preserves the structures and archeological site features for pride and educational purposes, serving the San Angelo, Texas community.

Sherley Spears

NAACP Unit 6219 President, Vice President of the National Historic Landmark Fort Concho Museum Board, and founder of the Buffalo Soldier Project.

One significant story coming from Fort Concho and the San Angelo community is the contributions and community development of and by the Buffalo Soldiers. On July 28, 1866, Congress passed the Army Organization Act, allowing African American men including many former slaves to serve in the specially created all-black military units following the Civil War. The original troops were 9th and 10th Cavalry and the 38th, 39th, 40th, and 41st Infantry. In 1869, the four infantry regiments were reorganized to form the 24th and 25th Infantry. Eventually, troops from each of these regiments served at Fort Concho. These black troops would be given the name ”Buffalo Soldiers," allegedly, by the Indian tribes because of their dark, thick, curly hair resembling buffalo hair. Fort Concho, originally established in 1867, was built for soldiers protecting frontier settlers traveling west against Indian tribes in the area.

Buffalo Soldiers

Buffalo Soldiers of the American 10th Cavalry Regiment

A notable member of the San Angelo community was Elijah Cox, a retired soldier from the 10th Cavalry. While never stationed with the Buffalo Soldiers at Fort Concho, Cox lived and worked many jobs there. He was a well-known musician and played for many of the socials and events held at Fort Concho. Elijah was a fiddler, he and his son, Ben played for all of the dances at the Fort. Elijah, born and remained a freeman, settled in San Angelo, Texas, and would learn the songs of the slave from ex-slaves now soldiers. Elijah would become the traditional bearer of these songs as he played fiddle, guitar, and sang. You can hear my podcast on his story here.

FULL NEW EPISODE FEATURING SHERLEY SPEARS

These, and much more crucial historic narratives are being preserved by Ms. Sherley Spears and the organizations adamant of raising the awareness of African American contributions to the establishment and sustainability of Fort Concho & San Angelo, Texas.