COLONIALISM & INSTITUTIONS

White Colonial Ideologies and the Institutionalization of Power

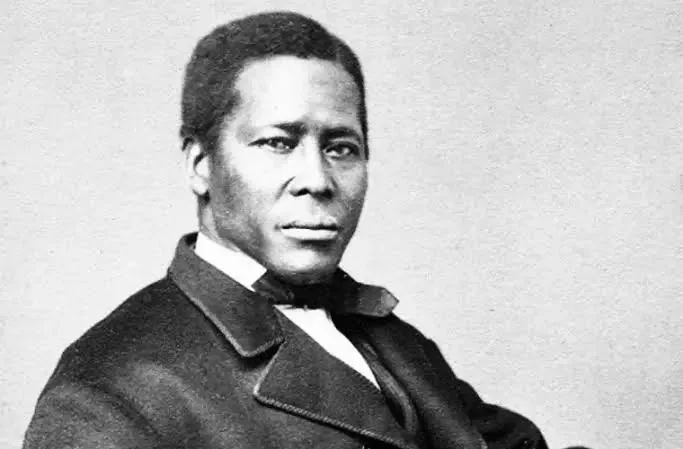

William Still: Black Ethnographer of the Underground

William Still wasn’t just recording history. He was practicing a distinctly Black ethnographic methodology grounded in survival, storytelling, and freedom.

By Lamont Jack Pearley

“More than a conductor on the Underground Railroad or the secretary of an historically Black organization, William Still was an early Black ethnographer—archiving memory, testimony, and survival from within the movement itself.”

When we speak the names of our ancestors who laid the groundwork for what we now call Black folklore and fieldwork, it’s crucial that we include William Still.

Many recognize Still as the “Father of the Underground Railroad,” the free Black man in Philadelphia who helped hundreds of freedom seekers escape bondage. That legacy is powerful, and it’s true. However, what often goes unspoken is that Still, through his 1872 book The Underground Railroad, wasn’t just a freedom fighter; he was a fieldworker, a documentarian, and a cultural preservationist. Essentially, Still, like Charlotte Forten Grimkè (whom Still comes out of her family’s camp) was an ethnographer, utilizing folkloristic methods. He was doing the work we now identify as ethnography and Black folkloristics long before those terms were formalized or acknowledged within the academy. Even before Childs, Newells, Brinton, and Boas thought to utilize a Euro lens at what they called “advocating for the respect and understanding of diverse human cultures and traditions..”

Still’s work represents one of the earliest examples of community-rooted field documentation, carried out not from a distance, but from within the very movement it preserved. He created a collection of what is referred to as primary source material.

A Fieldworker in the Fight

Still didn’t interview his subjects years later in comfort. He sat with them immediately upon arrival, sometimes the same day they escaped slavery. He took down their names, places of origin, escape routes, kinfolk left behind, and in many cases, their own personal philosophies. These weren’t secondhand reports or reimagined tales; this was real-time testimony, captured from within the movement itself.

That makes William Still a participant observer, an embedded witness, not just to the facts of escape, but to the internal, spiritual, and familial world of the people in motion. He was practicing what we today call field ethnography, gathering firsthand accounts, contextual details, vernacular language, and deeply cultural expressions from those who lived through it as he led them to their destinations.

He wasn’t collecting data for the sake of scholarship. He was preserving Black memory, so it couldn’t be erased, distorted, or forgotten. He had purpose!

The Archive as Resistance

What distinguishes Still’s work from many other abolitionist documents of the time is that he prioritized Black voice and agency. He didn’t translate their stories into respectable terms for white audiences. He didn’t flatten or edit their words to fit a political script. He let the people speak. He recorded their truths on their own terms. A methodology championed by ethnomusicologists and folklorists currently, as most have come to realize the initial aesthetics and practices of the field and discipline have been racist, sexist, and replete with class warfare.

That’s not just abolitionist work, it’s counter-archival work. Counterintuitively, it is archiving through the lens of what is significant to Black Americans and Afro-Indigenous framing—not archiving and collecting based on outside understanding of what would constitute communal black memory to move the tribes and peoples forward. Still built a repository of Black narrative ownership, one that resisted erasure and claimed the right to document life, pain, joy, and freedom in our own voices. Still gave us the blueprint of black documentation, repository, and archiving for the field ethnographic interviews conducted by insiders. Insiders, in the sense of Black voices documenting Black voices.

Still’s archive includes spiritual beliefs, coded songs, family stories, resistance strategies, and moral convictions. It mirrors today’s folkloristic methods, centered on lived experience, oral tradition, and community truth-telling. Not only did he work as a public folklorist, but he also applied early methods of ethnomusicology, as Still documented the engagement of the folks he interviewed with their music and sonic expression.

A Method Rooted in Culture

From a folklorist’s standpoint, Still’s book is filled with the elements we seek when we enter the field: kinship structures, regional knowledge, spiritual worldview, vernacular storytelling, and historical context embedded in everyday life. He didn’t just collect who went where; he preserved how they thought, what they believed, and why they moved the way they did.

This kind of documentation is what I call Black cultural fieldwork, not just recording for the sake of records, but preserving for continuity, justice, and cultural memory. Essentially, this is the precursor to the Blues Narrative. Still’s methodology was informed not by theory, but by responsibility. A responsibility that lives in ethics! Still didn’t have to develop ethics to conduct his work; his work was born out of the sensitivity and treatment of his people. Out of a cotastraphe, out of war, natural disaster, ultimately, out of prisoners of war named slaves. He understood the weight of the moment and responded with care.

His work is a model of Blues People Preservation: rooted in the community, accountable to the community, and crafted to safeguard the legacy of Black life as told by those who lived it.

What This Means for Us

As a practicing folklorist, traditional Bluesman, and cultural preservationist, I often turn back to Still, not just for his content, but for his approach. He reminds us that fieldwork is not neutral. It’s a choice. And when done right, it’s an act of love and resistance.

In a time when Black stories are still commodified or misrepresented, Still’s work teaches us that to document our people means to honor them, to believe them, and to trust their voice over interpretation. There is no talk of ethics or this idea of objectivity. Still approaches as an applied ethnomusicologist and applied Folklorist,

Still’s legacy lives in every oral history I collect, every field recording I make, every sacred story I preserve. His pen was a tool of liberation. His book is a cultural lifeline.

We Are Still Building

At The African American Folklorist, our mission aligns with Still’s foundational work. We uplift and amplify Black voices, not as subjects but as narrators, theorists, and keepers of knowledge. We build our archives not only to preserve the past, but to affirm the present and shape the future.

William Still wasn’t just recording history. He was practicing a distinctly Black ethnographic methodology grounded in survival, storytelling, and freedom. It’s time we place him alongside our greatest cultural scholars, not just for what he did, but for how he did it.

And so, we carry the torch, not just of freedom, but of Black fieldwork that listens, documents, and preserves with purpose.

Lamont Jack Pearley is a traditional Blues artist, public folklorist, and founder of the Jack Dappa Blues Heritage Preservation Foundation and The African American Folklorist Magazine. His work centers the voice, memory, and lived experience of the Black Blues People through research, music, oral history, and cultural fieldwork.

“The Archive Is Alive: We Are What They Imagined

In the Black folk tradition, we say the ancestors are always speaking. You just have to listen. The African American Folklorist was born out of that deep listening. It is not simply a magazine, platform, or project—it is a response. A call and response, to be exact. We are answering the calls of those who came before, affirming their intellectual labor, carrying forward their cultural vision, and transforming their blueprints into living, breathing work.

Written By: Lamont Jack Pearley

How Foundational Black Thinkers Confirm and Call for the Work of The African American Folklorist

The African American Folklorist platform is a contemporary manifestation of the intellectual, cultural, and spiritual legacy left by Black scholars, activists, cultural workers, and theorists. Many of these individuals called for or modeled the very practices now embedded in the African American Folklorist’s mission—oral history collection, community-based publishing, cultural repatriation, and the interpretation of Black life through the lens of folklore, Blues, and lived experience.

The Archive Is Alive: We Are What They Imagined — Confirmed by the Ancestors, The African American Folklorist as Continuum

In the Black folk tradition, we say the ancestors are always speaking. You just have to listen. The African American Folklorist was born out of that deep listening. It is not simply a magazine, platform, or project—it is a response. A call and response, to be exact. We are answering the calls of those who came before, affirming their intellectual labor, carrying forward their cultural vision, and transforming their blueprints into living, breathing work. This essay traces how foundational Black thinkers, scholars, and cultural workers have not only confirmed our mission but, in many ways, demanded it. This is a chorus of lineage, and we are its next verse.

W.E.B. Du Bois laid the foundation with his insistence on documenting Black life through a lens that recognized its soul, its sorrow songs, and its sociological richness. In The Souls of Black Folk, and even more so in his Georgia fieldwork, Du Bois called for what we now recognize as folklore work rooted in lived Black experience. His vision of cultural science from within is a direct ancestor to the Blues Narrative we carry forward today.

Arturo Schomburg reminded us that the Black archive is not optional—it is essential. By insisting on the collection and preservation of Black cultural materials, Schomburg emphasized that self-representation is historical reclamation. The African American Folklorist, in all its formats—print, digital, audio, and live broadcast—embodies that ethos. We are not collecting for curiosity; we are archiving for sovereignty.

Carter G. Woodson democratized the discipline. By founding Negro History Week and writing for everyday people, he validated community-led knowledge production. Our platform exists in that same spirit, guided by the belief that tradition bearers, community scholars, and culture keepers are theorists in their own right. Like Woodson, we reject the ivory tower as the sole house of knowledge.

Anna Julia Cooper ensured that Black women’s voices were never footnotes. She spoke from the intersection before it was named as such, claiming space for Black women as central agents in cultural theory and preservation. Our "Women's Folklife" series and the Black Blues Women project echo her call.

John Wesley Work III quietly modeled what we now do loudly—he collected, documented, and dignified Black music as a folklorist. His fieldwork on spirituals and Blues set the stage for the Blues Ecology framework we now build upon: music as memory, landscape, and liberation.

LeRoi Jones, later Amiri Baraka, did not merely describe Black music; he politicized it. Blues People is a map of our musical epistemology. Through Baraka, we understand that every moan, shout, and lyric is a historical document. Our podcast episodes, narrative essays, and musical analyses stand on his shoulders.

James Cone gave us the theology. He revealed that the spirituals and the Blues are not oppositional but deeply entwined expressions of Black theology. When we speak of Slave Seculars as sacred testimony, we are echoing Cone’s liberation theology with a folklorist's ear.

John Henrik Clarke demanded that Black people write, teach, and theorize their own history. He modeled intellectual sovereignty, which is the bedrock of our editorial and fieldwork ethos. Our contributors are not just writers—they are cultural witnesses.

Michael Gomez traced the continuity from Africa to the American South, from country marks to communal memory. His diasporic methodology informs our cultural documentation of Blues people, African survivals, and folk traditions that span generations.

bell hooks, in Black Looks and beyond, urged us to view Black cultural production as resistance and as love. She reminded us that theory lives in the everyday. Our magazine and platform bring theory to the porch, the juke joint, the sanctuary, and the street.

The Negro Women’s Club Movement were grassroots folklorists before the term became academic. They held pageants, collected oral histories, and preserved foodways. We follow in their tradition by uplifting vernacular knowledge and celebrating communal care as cultural labor.

Charlotte Forten Grimké documented the everyday life of Black folk during Reconstruction—a proto-ethnographer who reminds us that journaling, witnessing, and testifying are tools of survival and scholarship. Our fieldnotes echo her pen.

Alexander Crummell believed in Black moral uplift and nationalism. His call for sovereignty undergirds our push for Black cultural self-determination through folklore.

Chancellor Williams, in The Destruction of Black Civilization, offered historical repair through people’s history. That same repair is what we aim to enact in our heritage and repatriation work.

Nathaniel Norment Jr. advocated for Black rhetorical traditions as identity formation. We continue this by affirming storytelling, performance, and vernacular speech as theoretical frameworks.

Anthony Benezet, though not Black, represents early allyship in educational justice. His presence reminds us that solidarity is a practice, not a slogan.

James Forten and his family legacy supported abolition and Black education through print culture. We are his digital descendants, publishing for liberation.

Kimberly R. Norton represents our scholarly present and future. Her work in Black cultural heritage and folklore bridges the academic and the communal, much like our mission.

We are the living archive. We are the embodied return. The African American Folklorist is not just a publication; it is confirmation. Confirmation that the ancestors dreamed us. That they theorized this work. That they laid the foundation so we could build. And now, build we must.

Copyrights 2025

The idea that major record labels will be devastated by the wave of artists reclaiming their copyrights is almost laughable, especially when considering what these labels currently own and control.

Written By:

Allen Johnston

Music Specialist

Big Joe Turner

The idea that major record labels will be devastated by the wave of artists reclaiming their

copyrights is almost laughable, especially when considering what these labels currently own

and control.

Major record companies have long relied on their back catalog as a built-in revenue stream.

Sales of CDs, digital streams, vinyl, and live performance recordings continue to sustain them

while revenue from new artists remains unpredictable. Over the decades, these corporations

have strategically structured the industry in their favor.

During the 1980s, major labels executed a plan that dismantled independent Black and White

retailers while securing dominance over distribution. They introduced the SoundScan system,

offering free computers to independent store owners and coalitions. This initiative gave labels

direct access to sales data, allowing them to pinpoint which catalog titles were consistent

sellers. With this knowledge, they could optimize manufacturing costs while maximizing profits.

Since they owned the copyrights, they essentially paid themselves through mechanical,

synchronization, and performance publishing rights.Recording contracts from that era—and even before—ensured that major labels retained nearlyall revenue streams from copyrights. Artists were left with only a fraction of publishing revenue, limited performance royalties, and sometimes a cut of merchandising. PA (musical composition) and SR (sound recording) copyrights for nearly every hit song before 1984 remain under the ownership or control of a major label or one of its affiliates. For instance, Sony Music might control the SR copyright of a song, hold at least 50% of the PA copyright through contractual agreements, and place the composition within its wholly owned publishing division. This setup allowed money to circulate internally, with one corporate division paying another. Additionally, many artists had taken advances against royalties, leading to labels claiming ownership over original songwriter shares as well.

Artists affected by these agreements include, but are not limited to: Aretha Franklin, Marvin Gaye, Otis Redding, Ray Charles, Chuck Berry, James Brown, Clyde McPhatter & The Drifters, Big Joe Turner, The Temptations, Little Richard, Wilson Pickett, Fats Domino, The Dominoes, Sly & The Family Stone, Lloyd Price, Martha & The Vandellas, Parliament-Funkadelic, The Four Tops, The Isley Brothers, Jackie Wilson, Smokey Robinson & The Miracles, Kool & The Gang, The Supremes, Frankie Lymon & The Teenagers, Earth, Wind & Fire, and many more.

Even in the worst-case scenario, where some artists reclaim their rights, major labels will simply renegotiate with savvy copyright owners who have financial leverage. For everyone else, it will remain business as usual—offering advances in exchange for new contracts.

These catalogs retain immense value in the digital age, particularly in streaming, film and commercial licensing, and corporate partnerships. With their industry connections, financial muscle, and technological infrastructure, major labels remain well-positioned to continue profiting from these assets.

Harvard Cancels Slavery Research program

Harvard recently fired researchers for their Slavery Remembrance program without notice

Update on a troubling situation!

By: Kristina Mullenix, the Alabama Storykeeper

Harvard recently fired researchers for their Slavery Remembrance program without notice and after researchers uncovered links to slavery in Antigua and Barbuda. In September, the vice provost had told them "don't find too many descendants." The project, according to news, has been handed over to American Ancestors in Boston.

Link from Instagram about firing:

https://www.instagram.com/reel/DFTAEpjJn9q/?igsh=MW5yanJ6cm1zajd5aw==

News articles about the situation:

https://www.thecrimson.com/article/2025/1/24/harvard-disbands-slavery-remembrance-program/

This is the website about the project (still on their webpage):

the culture of black girl tokenism

Growing up, seeing black girls on television made me appreciate my skin color and inspired me to be an actress. But I never really paid close attention to the role of black girls on syndicated cable shows. Lately I've noticed that a lot of black roles in programs I watch are grounded in tokenism. Tokenism was established in the 1950s and was termed in the 1970s. In the late 60s and early 70s another form of token was established, “the token black”. According to Ruth Thibodeau in her piece From Racism to Tokenism:

BY: SAMARA PEARLEY

Growing up, seeing black girls on television made me appreciate my skin color and inspired me to be an actress. But I never really paid close attention to the role of black girls on syndicated cable shows. Lately I've noticed that a lot of black roles in programs I watch are grounded in tokenism. Tokenism was established in the 1950s and was termed in the 1970s. In the late 60s and early 70s another form of token was established, “the token black”. According to Ruth Thibodeau in her piece From Racism to Tokenism: The Changing Face Of Blacks in New Yorker Cartoons, “cartoons were mostly racially themed, and depicted black people in token roles where they are only there to create a sense of inclusion”. Though Ruth was speaking specifically about cartoons, this idea can be applied to any medium featuring only one black character. Today in an era of DEI (diversity, equity, inclusion) we see the same things Thibodeau described in her writings. Tokenism strongly suggests the one black character among the many non black means a diverse voice or cast. To be fair, tokenism also includes members of the BIPOC and LGBTQIA community in predominantly white programs, but for the purpose of my scholarship, I'm focusing on black girls. Being a token means being different from the rest of the group in order to create some kind of diversity. Tokenism is a tactic, strategy used to get the optics of inclusion for marginalized people. Unwelcome Guest on the website Antimoon.com states: “An example of a token black would be a black person who is hired in a company, not because of his or her skills but because the company is by law to hire black people. It's not a derogatory term.”

Monique Coleman would be a good example of tokenism. She is the only black-non mixed character in a predominantly white cast. Monique is well known for being on the hit Disney channel original movie (DCOM) High School Musical. In an interview in December of 2022 with Christy Carlson Romano, Coleman states that “disney broke her heart”. Coleman went on to say how they left her out of the high school musical promo tour. She says their reasoning for leaving her and another cast member out was because “they didn't have enough room on the plane”. I find it suspicious how she was on the front cover of all the movies, one of the main characters, and her character Taylor was the smartest girl in school, but she wasn't on the tour? I'm sure Disney had enough resources to accommodate Monique. Coleman’s castmate is Corbin Bleu who is mixed. Do you find it suspicious that he got invited on the plane and Monique didn't? He gets to wear his natural hair but she doesn't? For example, in an article published by the Guardian, Coleman states that her hair stylist for high school musical did her hair very poorly in the front. And because of that she suggested wearing headbands so the stylists wouldn't have to cover her hair up with a hat everytime she was on screen.

Tokenism leads to stereotypes as well as mistreatment of black actors. It can also result in short lived programming of African American content. A result of mistreatment of blacks as a whole in this space is, black shows don't have the same life as non black shows, whether the show is good or bad. For example True Jackson v.p a show about a Black girl named True who was offered a job at mad style (a predominantly white fashion company) as the vice president of their teen apparel department. Keke Palmer is the main character of this show. This show got canceled after 2 seasons. Keke Palmer is in the process of trying to get theTtrue Jackson V.P. reboot done, while her counterparts iCarly and Zoey 101 have gotten, approved, and aired their reboots. Is this based on race? I can't say. However the track record of disparity between blacks and whites are very real. Recently Nickelodeon has been airing a show titled “That Girl Lay Lay” with not only 2 black girl leads but a predominantly black cast! There's no information on whether it's getting renewed or canceled, but I hope that this show can get a 3rd season. There's a lot of work to be done but this show signifies progress.

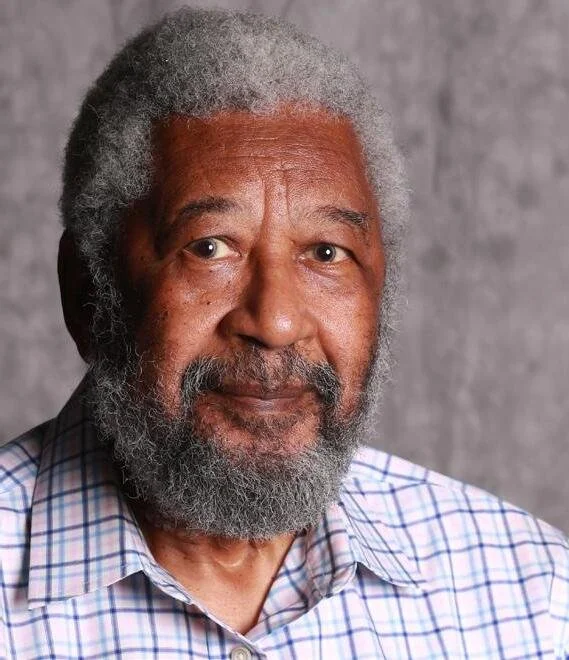

John H. Bracey, Jr., a pioneer of Black Studies

Andrew Rosa, author (top row, second from left); John H. Bracey, Jr. (front row, fourth from left), Annual Meeting of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History, Charleston, South Carolina Oct. 2, 2019.

BY: DR ANDREW ROSA

In “the Grand Tradition”: A Reflection on the Passing of John H. Bracey, Jr., a pioneer of Black Studies Western Kentucky University

“To teach is to mentor, and to mentor is to teach and lead students out,” John H. Bracey, Jr., 2019

Historians are, by and large, not noted for introspection. Our calling requires us to analyze past events, but rarely do we turn our interpretive talents upon ourselves. The occasion of John H. Bracey’s recent passing from the scene at the age of 81, however, has prompted me to reflect upon his significance to the field of Black studies and to my own evolution as a scholar of Black history. While beyond the scope of this reflection, I contend that any comprehensive examination of Bracey’s life history would illuminate an important genealogy of Black intellectualism essential to an understanding of the history of Black studies and a model for doing Black history at a moment when many states, especially across the U.S. South, seem to be engaged in a general assault on any type of knowledge that interrogates such critical issues as race, sex, gender, and class.

My relationship to Bracey began when I arrived to the W.E.B. Du Bois Department of African American Studies at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst in 1998, after receiving my masters from Temple University. In the broader history of Black studies, Temple is distinguished for establishing the first PhD-granting program in the field and for capturing, by the time I got there in 1995, significant media attention due, in no small part, to its Afrocentric orientation and to the charisma, entrepreneurialism, scholarly productivity, and rhetorical acumen of its chairperson, Molefi Kete Asante. Who could but forget the noisy academic battles that erupted during this period between Asante and the Wellesley classicist Mary Lefkowitz over how much, if anything, the civilizations of ancient Greece and Rome, and all Western thought for that matter, owed to the cultures of Africa, and particularly Egypt. This debate resulted in some notable books by Asante and Lefkowitz, as well as several acerbic essays in such popular outlets as The Washington Post, and Village Voice. In this way Afrocentricity was introduced to a wider public as a combination of racial romanticism, historical mythmaking, popular history, and the paradigmatic antithesis of Eurocentricity in that it purported to be a corrective to the wholesale exclusion of Africa and Africans from the unfolding of world history.

To be clear, my choice of Temple for graduate school was not rooted in a desire to study under Asante, or by any unquestionable commitment to Afrocentrism. In fact, I knew very little about either at the time, and simply chose Temple because it was considered the premier graduate program in Black studies and I was offered a full ride in the form of a Future Faculty Fellowship, which aimed to increase the number of minority faculty in the professoriate. More than this, Temple offered me the opportunity to continue a course of study that began when I was an undergraduate student at Hampshire College where I felt as if I walked in the shadows of Great Barrington’s own W.E.B. Du Bois and the writer extraordinaire James Baldwin, who briefly taught in the Five College Consortium as a visiting faculty, before returning to the south of France where he died a few years before I started my undergraduate journey. At Hampshire, I had the good fortune of studying under the likes of Robert Coles, e. francis white, Michael Ford, Andrew Salkey, and David Blight, to name a few. Each of these individuals shaped how I first began to seriously analyze the history, culture, and contributions of people of African descent to U.S. society, which led me into the interdisciplinary field of Black studies.

At Temple I came to appreciate how Afrocentrism represented a distinct school of thought within the larger universe of Black studies and, beyond this, an important variant in a long tradition of Black intellectualism that, since the early nineteenth century, defended Black capacity from attack by marking the achievements of African civilizations in the long centuries before European contact and the rise of racial slavery. For Asante, Afrocentricity’s centering of African knowledge systems made it the ideal foundational philosophy for the discipline; however, I came to reject efforts to impose a single methodology on doing Black studies, seeing it as stifling, unrealistic, and anti-intellectual. Moreover, as one who grew up in diverse working-class communities on both side of the Atlantic, Afrocentricity seemed to me to reinforce troubling discourses and hierarchies, and fell well short, as a research methodology, for engaging with the actual history and cultures of Africa. In addition to its inability to account for the hybrid identities and experiences across Africa and its diaspora, Afrocentricity’s emphasis on the dynastic universe of ancient Nile River Valley civilization made, in my view, little room for considering the contributions of Black people to the making of the New World and and an understanding of the myriad transformations wrought by the process of enslavement and colonialism.

It was this type of interrogation that led me to join the doctoral program at UMass where I was one of five students admitted into the History track of the program’s second class. It was here where I developed a wider understanding of Black Studies’ history and learned how the UMass program was uniquely connected to Black movement history. In fact, it seemed as if the department’s founding faculty rode into academia on a wave of campus revolts, the freedom movement in the South, and several militant organizations that took hold in cities across the country in the era of Black Power. The department’s first acting head, Michael Thelwell, was a close confidant of Kwame Toure (Stockley Carmichael) and a founding member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) at Howard University. As a student at Bennett College, where she now serves as provost, Esther Terry participated in the sit-in movement in Greensboro, North Carolina and was instrumental in the founding of SNCC. Ernest Allen, Jr. was active in the Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM) and became a leading historian on Black nationalism; William Strickland was Malcom X’s biographer and a founding member, along with Vincent Harding, of the Atlanta-based Institute of the Black World (IBW)—a grassroots organization committed to bringing Black studies into Black communities.

Of John Bracey, he arrived to UMass in 1972 by way of Howard University in Washington, D.C. and Chicago where he attended both Roosevelt University and Northwestern University. At Roosevelt, Bracey came under the influence of the linguist Lorenzo Turner, Charles Hamilton, coauthor of Black Power (1967), August Meier, an historian of Black intellectual history, and, most significantly, St. Clair Drake, a trailblazer in urban sociology and a pioneering figure in both African and African American studies. At Northwestern, Bracey became involved in the Black studies movement along with the likes of James Turner, Christopher Reed, and Darlene Clark Hine, all leading figures in the field of Black Studies today.

As with most of the founding faculty of the Du Bois Department, Bracey was active in the civil rights, Black liberation, and peace movements, working with the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), Chicago Friends of SNCC, Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), and RAM. Bracey often recalled how his arrival to UMass was the result of a request from Du Bois himself to hire the executor of his estate, the historian, Communist, and author of American Negro Slave Revolt (1943), Herbert Aptheker, as a condition of acquiring his personal papers. Meeting resistance from the Massachusetts legislature, Aptheker advised Thelwell to request five new faculty lines for the department in his place, one of which became Bracey’s position. More than underscoring the curious intersection of Cold War politics and Black studies, this story of Bracey’s joining UMass points to the insistence of the department’s founding faculty to protect their autonomy in building a program that would advance Black scholarship and mobilize knowledge for the liberation of Black peoples and all other exploited groups worldwide.

In the long years after the battle over Black studies had been won and new questions arose as to theory, methodology, and the place of the discipline in relation to larger Black community, Bracey was instrumental in moving the Du Bois Department forward by bringing in a host of brilliant faculty who were at the forefront of charting new directions in the field of Black studies. Over the course of a career that spanned more than a half century, Bracey established himself as a giant in Black studies and a veritable institution within himself. A lifetime member of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH), National Council of Black Studies (NCBS), and the Organization of American Historians (OAH) Bracey’s significance and presence were felt across the profession. As a scholar with an enormous range of interests and competencies, he resists simple definition. He wrote several award-winning works on Black life and history, and produced the kind of documentary and bibliographic research that gave textual substance to Black studies; all of this he made accessible to scholars, teachers, and students.

Bracey was also a consummate collaborator, working with such prominent thinkers as Sharon Harley, August Meier, James Smethurst Manisha Sinha, Sonia Sanchez, and Elliott Rudwick, to name just a few. While much of his writing and research focused on Black social and cultural history, radical ideologies and movements, and the history of Black women, he also produced comparative and transnational histories, which explored, for example, relations between African Americans and Native Americans, Afro-Latinx, and Jewish Americans. This includes several co-edited volumes, such as Black Nationalism in America (1970); the award-winning African American Women and the Vote: 1837-1965 (1997); Strangers and Neighbors: Relations between Blacks and Jews in the United States (1999); and African American Mosaic: A Documentary History from the Slave Trade to the Twenty-First Century (2004). From an award-winning essay on the musician John Coltrane in the Massachusetts Review in 2016 to his contribution to the Furious Flower poetry anthology in 2019, even Bracey’s final works stand as testaments to his interdisciplinary imagination, creative spirit, and genuine love for Black people.

As a model for Black studies, Bracey’s legacy suggests that the best of the discipline is in its interdisciplinary approach to knowledge production, its embrace of scholarly rigor and analysis, and in its mindfulness of the history, culture, and contributions made by people of African descent in the U.S., and throughout the African diaspora. Despite the many transformations that have accompanied the institutionalization and expansion of Black studies in American higher education, for Bracey, the discipline’s priority commitment to subjecting society to the most serious analysis to generate greater understanding of Black people’s experiences in the modern world was one that always remained steadfast and foundational to the Black studies enterprise.

I cannot help but to think of how my own work documenting the life history of St. Clair Drake was perhaps inspired by the genuine affection Bracey carried for his Roosevelt mentor and their shared commitment to the field of Black studies. As he once informed me, “Drake was my teacher and guide in the struggle.” For this reason, the idea of building an interdisciplinary department of scholar-activists at UMass “was not that utopian. After all,” he concluded, “we had Professor Drake himself—co-author [with Horace Cayton] of Black Metropolis (1945), Pan Africanist and advisor to Kwame Nkrumah, participant in civil rights marches and sit-ins for over three decades, sociologist, anthropologist and political theorist—as a model.” In this way Bracey laid claim to an intellectual estate that can be traced, through Drake, to Black studies earlier peripheries, particularly to those sites where Black intellectuals were free to combine scholarship and militant activism in what Drake called “the grand tradition.”

Buffalo Soldier Project, San Angelo Texas, and Black History

In this episode of the African American Folklorist, I speak with Sherley Spears, NAACP Unit 6219 President, President of the National Historic Landmark Fort Concho, and founder of the Buffalo Soldier Project. The National Historic Landmark Fort Concho Museum preserves the structures and archeological site features for pride and educational purposes, serving the San Angelo, Texas community.

By Lamont Jack Pearley

In this episode of the African American Folklorist, I speak with Sherley Spears, NAACP Unit 6219 President, Vice President of the National Historic Landmark Fort Concho Museum Board, and founder of the Buffalo Soldier Project. The National Historic Landmark Fort Concho Museum preserves the structures and archeological site features for pride and educational purposes, serving the San Angelo, Texas community.

Sherley Spears

NAACP Unit 6219 President, Vice President of the National Historic Landmark Fort Concho Museum Board, and founder of the Buffalo Soldier Project.

One significant story coming from Fort Concho and the San Angelo community is the contributions and community development of and by the Buffalo Soldiers. On July 28, 1866, Congress passed the Army Organization Act, allowing African American men including many former slaves to serve in the specially created all-black military units following the Civil War. The original troops were 9th and 10th Cavalry and the 38th, 39th, 40th, and 41st Infantry. In 1869, the four infantry regiments were reorganized to form the 24th and 25th Infantry. Eventually, troops from each of these regiments served at Fort Concho. These black troops would be given the name ”Buffalo Soldiers," allegedly, by the Indian tribes because of their dark, thick, curly hair resembling buffalo hair. Fort Concho, originally established in 1867, was built for soldiers protecting frontier settlers traveling west against Indian tribes in the area.

Buffalo Soldiers

Buffalo Soldiers of the American 10th Cavalry Regiment

A notable member of the San Angelo community was Elijah Cox, a retired soldier from the 10th Cavalry. While never stationed with the Buffalo Soldiers at Fort Concho, Cox lived and worked many jobs there. He was a well-known musician and played for many of the socials and events held at Fort Concho. Elijah was a fiddler, he and his son, Ben played for all of the dances at the Fort. Elijah, born and remained a freeman, settled in San Angelo, Texas, and would learn the songs of the slave from ex-slaves now soldiers. Elijah would become the traditional bearer of these songs as he played fiddle, guitar, and sang. You can hear my podcast on his story here.

FULL NEW EPISODE FEATURING SHERLEY SPEARS

These, and much more crucial historic narratives are being preserved by Ms. Sherley Spears and the organizations adamant of raising the awareness of African American contributions to the establishment and sustainability of Fort Concho & San Angelo, Texas.