arts & culture

Honoring Expression Rooted in Memory and Movement

The Promise of Black Music Month

As the month of June concludes and we enter July, Black Music Month (or African American Music Heritage Month) follows in tow. The uniqueness of our time is the dynamism of Black music operating in the popular consciousness now more than ever.

Written By: Kyle Thompson

“Music is a world within itself, with a language we all understand.”

- Stevie Wonder

As the month of June concludes and we enter July, Black Music Month (or African American Music Heritage Month) follows in tow. The uniqueness of our time is the dynamism of Black music operating in the popular consciousness now more than ever. From Kendrick Lamar’s legendary Super Bowl performance, the box office hit Sinners, and Beyoncé’s Cowboy Carter tour, there is no shortage of great music and reflective art emerging during this time. One of the most fundamental questions, however, is what the “promise” of Black music is to the history of African Americans as a people, and the broader implications it has on America and the world.

Black Music Month – Some background.

Black Music Month was established by President Jimmy Carter in 1979 as a way to support the work of the Black Music Association, which was created by Philadelphia artists Kenny Gamble, Leon Huff, and Cleveland-Based DJ Ed Wright.

The first Black Music Month Celebration was hosted at the White House. Artists like Chuck Berry and Billy Eckstine were in attendance, along with many other musicians, to commemorate African American music. The month would not receive an official presidential proclamation until 2000, under President Bill Clinton. Later, President Barack Obama would rename the commemorative month “African American Music Appreciation Month” in 2016. In the proclamation, President Obama stated, “African-American music exemplifies the creative spirit at the heart of American identity and is among the most innovative and powerful art the world has ever known” (para. 1).

Why is this moment in time distinct?

The movie Sinners has brought revitalized attention to Blues music, which contributes to the broader zeitgeist on musicality in America. Sinners effectively presents folkloric and supernatural motifs in Blues music in a unique and stylized manner that has not been explored prominently in film up to this point. At the same time, the everyday lives of Black people continue forward. The Black church continues to operate as a fixture in the lives of Black people, and rap remains a dominant secular art form. Above all else, the humanity of Black people is central to these experiences, whether at the cookout, praising God, or attending concerts of prominent Black artists. Upon further analysis, one would find that musicians who play blues, perform in churches, or create the next viral rap summer anthem do so not just as an expression of a specific genre, but to provide a soundtrack to the Black experience at a given point in time. This soundtrack is lived by people who seek comfort in the divinity of God, escape from life’s challenges through relatable lyrics, and camaraderie at social events.

What is the Promise of Black Music Month?

Black music touches every corner of the globe and resonates across history, languages, and personal experiences. It honors the complexity of the Black experience by the multitudes of artists who put pen to paper, recorded in studios, or performed on stages to express themselves. How, then, can we think about what I call the “promise” of Black music month? What does this mean in terms of looking at Black music beyond just a simple monthly designation, but as an ongoing, persistent feature of the human condition expressed by African Americans?

To me, the promise of Black Music Month is honoring the expression of humanity across genre, style, and approach to music in the Black community. So much so that anyone, around the world, can find some piece of themselves in the music, too. I would furthermore suggest that Black Music Month is a reflection of America, and the diversity that is cultivated by lived experiences and regional differences, unified by cultural similarities that have shaped the essence of what it means to be Black in America. The ability for Black people to express themselves is the ability for America to see itself reflected in a community that survived challenges for centuries, yet still continues to thrive. It is this promise that opens the door for new artistry and genres to emerge, reflecting the soul of America.

The History of Black People in Advertisements and Commercials

In everyone's day-to-day life, they receive some form of information or entertainment. Whether it is on Television, Youtube, Movies, Billboards, Radio, and Newspapers. Everything I mentioned has one major thing in common, Commercials and Advertisements. The difference between the two is Commercials are usually broadcasted on Television or Radio, and Advertisements are usually Print Media. Commercials have been around since 1941 and Advertisements have been around since the early 1700s.

By: Lamont Pearley Jr.

In everyone's day-to-day life, they receive some form of information or entertainment. Whether it is on Television, Youtube, Movies, Billboards, Radio, and Newspapers. Everything I mentioned has one major thing in common, Commercials and Advertisements. The difference between the two is Commercials are usually broadcasted on Television or Radio, and Advertisements are usually Print Media. Commercials have been around since 1941 and Advertisements have been around since the early 1700s. The very first Commercial was aired for the Bulova Watch Company. The ad was only 10 seconds long and cost between 4 - 9 USD. Today, there is a big jump in price points since Commercials aired during the Super Bowl costs 7 Million USD for 30 seconds. Along with the origins of Commercials, there is a history of Black presentation in advertisements.

Black People weren’t always treated well throughout history and Commercials weren’t the exception. Black people were being used as a way to sell products to people, some examples being Aunt Jemima, Uncle Bens, and The Quintessential Mammy. The Quintessential Mammy is a stereotype depicting Black Women who work in White households and take care of children. She is usually visualized as a fat, dark-skinned woman with a motherly personality. This was the woman that was not only pivotal in the black community, but raised the children of white plantation owners, making her a comfortable image to white America. An article published by raceandethnicity.org explains Ads like “The Gent in the Window” are created as ways to promote their product and make White People feel comfortable reading these ads. From 1830 up until 1941 whenever a black person was shown in an Advertisement it was racially offensive. In 1948 Jax Beer created a Commercial called “Whistle up a party”, the first non-racist African American Commercial. This made an impact on how Black People would become viewed in Ads for the future.

Starting in the 1960’s the Civil Rights Movement made African American Advertisements an important issue to fix. Don Cornelius intentionally utilized black Advertising companies and businesses for Soul Train. An article on Soul Train by theguardian.com quotes Don saying “I want black folks to be seen how black folks should be seen: strong, powerful, and beautiful”. Soul Train was something black families could always look forward to watching, knowing that their people were being represented in a good light. John H. Johnson founded Ebony and Jet Magazines in 1945, the first Black Owned Advertisement company. Ebony and Jet Magazine published an issue in 1955 showing Emmett Till's dead corpse in a casket. During the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s, Ebony and Jet Magazines published multiple magazines about political events involving activists protesting racial violence and advocated for increasing social mobility for African Americans across the diaspora. The peak of Ebony and Jet Magazine was in the 1980s when they had a circulation of 2.3 million. In 2021 the changes that the Civil Rights Movement was fighting for became implemented on products such as Aunt Jemima brand changing to Pearl Milling Company. Uncle Ben’s also changed in 2020 from “Uncle Ben’s” to “Ben’s Original”. Due to the civil unrest that was going on in 2020 the majority of Commercials seen on television were related to Black Lives Matter. Companies and Brands were Advertising Black Lives Matter. For the whole month of February, the NBA had Black Lives Matter merchandise and logos on Jerseys.

A lot of historic black people made significant contributions to how African Americans would be viewed in Advertisements and Commercials. Vince Cullers created his own agency called Vince Cullers Advertising. He created this to help showcase and create Ads geared to African Americans. Then there is Carol H Williams. Williams started working in the Advertising Business in 1969 and created her business in 1986. She is the first African American female Creative Director to be inducted into the American Advertising Federation’s Advertising Hall of Fame in 2017.

Currently in media, we see black people in Advertisements all the time, at the very least more than in the past. What made this change happen? Many things. What I do know is the stories I mentioned should be talked about more to usher in a solution for equality.

the blues that sprung from my roots

Growing up, I was often teased by my peers in school for liking blues. I did not mind though. I preferred the culture and history of the Blues instead of consuming dominant pop culture at the time. I had no true explanation as to why I felt the way I did about the Blues- I just did. Being a black man from the suburbs was my way of engaging with my environment. Some people say the Blues is something that comes to you, rather than you coming to it.

BY: KYLE THOMPSON

Growing up, I was often teased by my peers in school for liking blues. I did not mind though. I preferred the culture and history of the Blues instead of consuming dominant pop culture at the time. I had no true explanation as to why I felt the way I did about the Blues- I just did. Being a black man from the suburbs was my way of engaging with my environment. Some people say the Blues is something that comes to you, rather than you coming to it. Other people say you get the blues over a person you love. I think both are true, in a way, but no one has to live a hard life to feel the Blues. I got the blues yesterday when I dropped my sandwich on the ground.

There is something to this magnificent music that draws my ears in a way like no other. People always say that there is that one song that you hear, and when it grabs you, it holds you to your very core. I would say most, if not all blues music I came in contact with had that effect on me. One benefit of growing up in the age of the internet was that I had options to craft my individuality the way I saw fit. In this case, I dived deep into the blues, because it was always at my fingertips. The way I saw it, why would I only listen to what was popular when I could literally explore any genre I wanted? I listened to punk, afrobeat, hip hop, gospel, and classical music. In each of these genres, I found the blues. It was so interesting to me understanding how everyone’s favorite band loved and admired the blues so greatly, yet everyday people didn’t seem to care about blues.

I quickly learned that people’s perception of the Blues were heavily misguided. Some people thought it was just a black man strumming a guitar down south singing about whiskey and women. Other people reduced its complexity to being just a music that gave birth to Rock n’ Roll. The Blues in this narrative was an antiquated sonic form, its only purpose being a stepping stone to the development of rock and roll. Very few people were intentional in saying what it actually was though- an African American art form. I see the blues as a folkloric element to the Black experience that is passed down through generations- verbally or nonverbally. When I was a child growing up, my grandfather would sit in the back of his truck and listen to the radio. Oftentimes, I would tag along, and together we would spend afternoons sitting in his car listening to Blues music on the radio. I was much younger then, barely past four or five, however I knew that what I was experiencing was something special. I had no words to describe what that experience felt like until years later, when I came across a well-known painting called The Banjo Lesson by Henry Ossawa Tanner. In that image, I saw an aesthetic contextualizing the relationship with my own grandfather- a Black man passing down culture and folklore to a younger generation.

The blues has roots in field hollers, slave spirituals, and work songs meant to uplift the spirits of enslaved Africans brought to America. The pain, hardship, and inequality of slavery would naturally bring about a sound of music and cultural expression reflective of their environment. As slavery became replaced by the impact of Jim Crow, it became a new barrier to the success of the Black community to achieve and thrive. The blues acted as that healing, secular music that would be a form of release after a long day of work. Musicians would channel their experiences into singing about their lives, their experiences, and their emotions. I hear more than an aesthetically pleasing sound of music listening to blues. I heard the sounds of grandparents and their elders, recorded so long ago. I hear backyard fish fries, I hear trains bustling down the railroad, I hear cottonfields, I hear cars driving up and down the city highway, I hear community centers, I hear Thanksgiving, I hear Christmas with family, and I hear vestiges of African culture. The lives, slang, style, and morals were wrapped in the painful and profound. In a sense, when I listened to the blues, I was receiving this heritage that was apart of a larger narrative and experience. I found where I fit in my own culture, and in turn, where America and the world fit in with my expression.

OKLAHOMA BLUES

Between the 1830s to 1850s, Native Americans of the Five Tribes were forcibly marched on the Trails of Tears from their homelands in the southeastern United States to the eastern part of modern Oklahoma, then called “Indian Territory.” With them, they brought their African American slaves. It must be understood that slavery in Indian Territory varied widely – ranging from resembling white cotton plantations, to commonly practicing intermarriage and allowing other extended freedoms. Linda Reese cites, “By the time of the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, the tribes' members owned approximately ten thousand slaves.”

BY: SELBY MINNER AND IRENE JOHNSON

“Da-dut – da-dah-duh – dah-de-dup!” My bass rang out across the crowd… I could hardly breathe! He had me starting the song as a solo – indeed the whole set! Up the steps he came, out from behind the stage and into the light, sporting a yellow ice cream suit and a big red guitar. The drums kicked in, the rest of the band, and then… Mr. Lowell Fulson hit the microphone and the place came alive: “TRAMP! You can call me that! But I’m a LOVER!” I was holding the bass line – one of the greatest bass lines. The man at the top of the West Coast blues was back home in Tulsa, and Juneteenth on Greenwood was rocking! D.C. was wearing “old shiny” – his green and red tux jacket – with his red guitar, Big Dave 'Bigfoot' Carr was in from Spencer, OK, with his sax, Jimmy Ellis on guitar and vocals, and Bob ‘Pacemaker’ Newham on traps. It was 1989 and Lowell Fulson was at home to be inducted into the Oklahoma Jazz Hall of Fame. He later said he would come back to play the Traditions Festival in Oklahoma City in the fall, but only if he had the same backup band! Such an honor to play with an Oklahoma legend!

Oklahoma’s unique history and heritage provided fertile ground to grow its particular blues sound. Before we can dive into the blues, though, we need to travel back to Oklahoma before it gained statehood in 1907. I call it the wild west – where anything could happen.

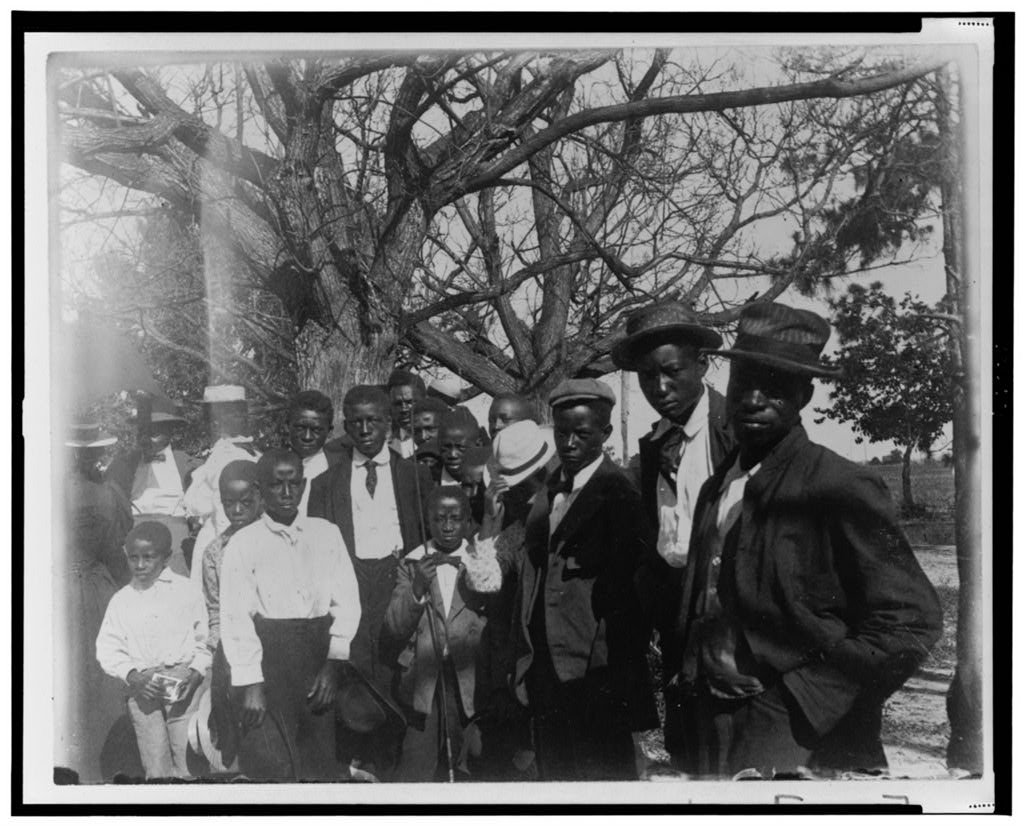

Between the 1830s to 1850s, Native Americans of the Five Tribes were forcibly marched on the Trails of Tears from their homelands in the southeastern United States to the eastern part of modern Oklahoma, then called “Indian Territory.” With them, they brought their African American slaves. It must be understood that slavery in Indian Territory varied widely – ranging from resembling white cotton plantations, to commonly practicing intermarriage and allowing other extended freedoms. Linda Reese cites, “By the time of the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, the tribes' members owned approximately ten thousand slaves.”1

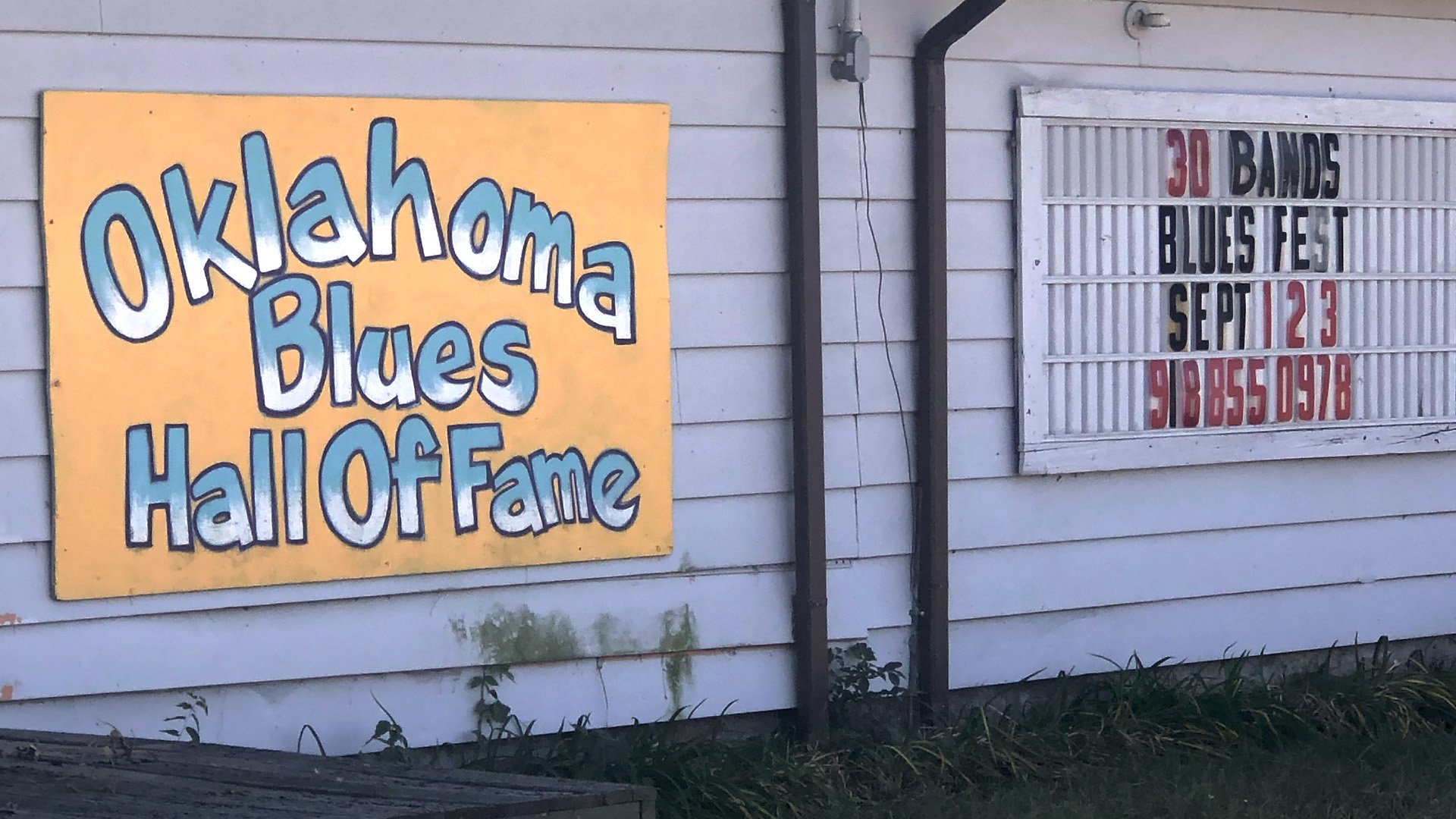

The Civil War was fought from 1861 to 1865. Dr. Hugh W. Foley, Jr. writes, “The Civil War’s presence in Indian Territory is directly related to Black pride in the area, as the Battle of Honey Springs, fought July 17, 1863, witnessed the first pitched combat by uniformed African American troops, the First Kansas Colored Volunteer Infantry Regiment, who fought alongside Anglo and American Indian troops. Fought just north of what is now Rentiesville, the battle has been called the ‘Gettysburg of the West.’”2 It was a running battle there at Honey Springs – some of it actually took place on our land where my husband D.C. Minner and I established the Down Home Blues Club (which hosts the Rentiesville Dusk ‘Til Dawn Blues Festival, the Oklahoma Blues Hall of Fame and the D.C. Minner Rentiesville Museum). Some of the soldiers from that battle went on to help found Rentiesville.

The end of the Civil War sparked big transitions for the “Twin Territories” of Indian Territory and Oklahoma Territory. Reese explains, “The government insisted on the abolition of slavery and the incorporation of the Freedmen [former slaves] into their respective tribal groups with full citizenship rights. All of the Indian nations were willing to end slavery, but citizenship rights conferred access to land and tribal monies as well as political power.”1 Despite tribal attempts to maintain control of their land and tribal monies through the U.S. courts, Freedmen were ultimately given full rights. The Dawes Act, which was the federal government’s way of breaking up commonly held tribal land into individual allotments, granted Freedmen “approximately two million acres of property, the largest transfer of land wealth to Black people in the history of the United States.”3

Reese goes on, “Freedmen from adjoining states had slipped into the territory for years, intermarrying with their Black Indian counterparts or homesteading illegally, but now the opening of Indian lands to non-Indian settlement gained momentum and brought hundreds of migrants both Black and white.”1 Oklahoma, considered the “First Stop Out of the South,” was indeed the “promised land” for about a 30-year window, offering land allotments and opportunity. It was close enough to the South to travel by wagon, folks could grow the same crops, and since it was not yet a state, there were no oppressive Jim Crow laws.

Freedmen often decided to settle together. It was at this point that the idea for all-Black towns developed. Larry O’Dell explains, “They created cohesive, prosperous farming communities that could support businesses, schools and churches, eventually forming towns. Entrepreneurs in these communities started every imaginable kind of business, including newspapers, and advertised throughout the South for settlers.”4 I’ve heard it said, the word was “tremendous opportunity, come help us do this… don’t come lazy and don’t come broke!”

The upshot of this opportunity was that more than 50 all-Black towns were established. These towns emphasized education, self-governance, strong churches and communities, and were held together by the economic security of their agricultural land. They believed that education was the key to a better future; the schools were strict and people graduated high school. My husband, Rentiesville native and bluesman D.C. Minner used to say, “If I did not get my lesson, I got a whoopin’ from the teacher. On my way home, my friend’s mom would give me a whoopin’, and when I got down here to the house Mama [his grandmother who raised him, Miss Lura] would give me a whoopin’, and she didn’t even want to know what I did wrong! If I got it from the others, she just had one coming too!”

Here’s where we can pick up on the music coming out of Oklahoma. Foley explains that the opportunities available during this time crafted the music legacy of the region; “Access to music lessons, instruments and mentors help explain why more African American musicians from Oklahoma developed the advanced musical skills necessary to evolve into jazz artists… As social and economic conditions changed for the state's African Americans by the 1920s and 1930s, more musicians born during that time period evolved into traditional, guitar-based practitioners of the blues.”5 Musicians who could read jazz charts went east and worked in almost every major jazz ensemble out of New York.

The jazz and blues players in Oklahoma were, in many ways, one community, particularly in major cities, such as Oklahoma City, Tulsa and Muskogee. In an interview with Bill Wax on Sirius XM’s B.B. King Bluesville, B.B. King said, “Jazz players say you can’t play good jazz unless you know the blues.” And D.C. said, “The R&B and blues bands here in the ‘50s and ‘60s all started their blues sets with an hour of instrumental jazz, so people could come in and get comfortable, and so the horn players could work out and do solos before they had to settle down to ‘blow parts’ – be rhythm players, essentially.” So, you see, there’s a blurred line there between jazz and blues here.

Given its history, plus the connection to Texas and the West Coast (you can drive to California without scaling the Rocky Mountains; there is a lot of work out there for musicians), I call Oklahoma – and Texas – “the cradle of the West Coast Blues.” Blues from Oklahoma is unique. Its sound includes horn sections, it’s a little smoother and the players dress – they consider themselves a little more “city” or “slicker.”

An integral part of Oklahoma’s blues sound developed with the Texas-Oklahoma “Hot Box” guitar style. Unlike the slide playing or finger picking styles from the Piedmont and Mississippi-Chicago sounds, the “Hot Box” guitar style is a single-note lead style that has a great local lineage that eventually crossed over to rock ‘n roll. Starting around 1900, players of this style include Blind Lemon Jefferson (possibly the earliest to record this style), jazz innovator Charlie Christian (the first to put electric guitar solos into jazz), T-Bone Walker, Freddie King, Stevie Ray Vaughan, B.B. King to Eric Clapton and beyond. The Hot Box single-note lead style is the style of most American rock ‘n roll to this day! B.B. King said in another Bill Wax interview, “I am from Mississippi, but my fingers are too lazy to play Mississippi style, I play Texas!”

There is no “music industry” per se in Oklahoma like there is in Nashville, Austin or Chicago; most people who play professionally work out of state. But since there are lots of juke joints in these towns – five in Rentiesville alone – there’s still a lot of music! Oklahoma has produced numerous great musicians and I’d love to tell about each and every one, but I’ll have to settle for highlighting just a few, with the help of Hugh W. Foley, Jr.’s “Blues” for the Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture.5

Hart Wand of Oklahoma City actually published “Dallas Blues,” the first 12-bar blues on sheet music, in March of 1912 – the same year W.C. Handy published “Memphis Blues,” widely considered the first blues song.

There were several territorial bands that played a circuit in the early 1900s across Oklahoma, Texas, Arkansas, Kansas, Missouri and Nebraska. The best of these bands was the Oklahoma City Blue Devils, which later became the core of the Count Basie Band out of Kansas City. Truly the bluesiest of all the touring jazz bands, I would say.

Jay McShann supplemented his passion for the blues with what he learned in the Manual Training High School band of Muskogee, OK, and went on to lead one of the great blues-based big bands of the 1930s and 1940s out of Kansas City. His "Confessin' the Blues" was one of the biggest selling records for a Black artist in the early ‘40s.5

Joe "The Honeydripper" Liggins charted a number of singles, including "The Honeydripper" and "Pink Champagne,” during the late 1940s and early 1950s with his streamlined rhythm and blues. His brother, Jimmy Liggins, led an amplified R&B group that preluded rock ‘n roll with hits like "Cadillac Boogie," "Saturday Night Boogie Man," "Drunk" and later, his now-classic blues song "I Ain't Drunk." Bandleader, drummer and songwriter Roy Milton’s “jump blues” served as a precursor to rock ‘n roll.5

Jimmy “Chank” Nolen was another of Oklahoma's important blues guitarists. Credited for inventing the "chicken scratch" guitar style, Nolen is considered the “father of funk guitar.”5 The chord on the guitar is played in such a way that is very percussive, like a drum beat. Since it makes guitar rhythms very danceable, James Brown picked Nolen up to record as primary guitarist on several major hits.

Gospel and soul-blues singer Ted Taylor experienced success with his falsetto-driven voice in the 1950s- ‘70s. Guitarist Wayne Bennett worked with Elmore James, Jimmy Reed, Otis Spann, Otis Rush and Bobby "Blue" Bland. Verbie Gene "Flash" Terry recorded the hit, "Her Name is Lou,” and later toured with T-Bone Walker, Bobby "Blue" Band, Floyd Dixon and others.5

Guitarist Jesse Ed Davis, a Native American with Comanche, Kiowa and Muscogee heritage, toured with Conway Twitty in the early ‘60s before moving to California and joining Taj Mahal. Davis’ “reputation led to sessions for Leon Russell, Jackson Browne, Eric Clapton, John Lennon, Ringo Starr and Captain Beefheart, as well as four of [his] own solo albums.”5

Larry Johnson and the New Breed (with D.C. Minner on bass) were the house band at the Bryant Center in Oklahoma City, playing several nights a week and backing up touring headliners like Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley for almost 10 years.

Lowell Fulson is probably Oklahoma’s most widely recognized blues guitar star. “By adding a horn section in the mode of swing bands to his electric blues lineup, Fulson created what is typically called the ‘uptown blues’ sound, which B. B. King made famous. Fulson's huge 1950 R&B hit, ‘Everyday I Have the Blues,’ became King's theme song”5 – surfacing the Texas-Oklahoma “Hot Box” guitar sound once again to evolve into what we know as the popular blues style!

Foley concludes, “Anglo-American blues men who emerged primarily from the Tulsa scene in the 1960s include pianist Leon Russell and guitarists J. J. Cale and Elvin Bishop.”5

I could keep going – multi-award-winning Watermelon Slim, extraordinary blues belter Dorothy “Miss Blues” Ellis, Jimmy Rushing of the Blue Devils and Count Basie's Orchestra, and so many more – but I’ll end my abridged round-up with my late husband, blues guitarist D.C. Minner.

D.C. was raised in Rentiesville by his grandmother, who owned and operated a grocery store/juke joint called the Cozy Corner in the 1940s- ‘60s. Here, he was exposed to all the music coming through. He toured, playing with Larry Johnson and the New Breed, Lowell Fulson, Chuck Berry, Freddie King, Bo Diddley, Jimmy Reed and Eddie Floyd before starting our own band, Blues on the Move. In 1988, we got tired of the road and moved from the California Bay Area back to Rentiesville, and reopened his grandmother’s old juke joint as the Down Home Blues Club.

In 1989, we established the Blues in the Schools program through the Oklahoma State Arts Council. In 1991, we started the Rentiesville Dusk 'Til Dawn Blues Festival to feature local and regional blues artists, and it has become the longest running blues festival in the state and renowned nationwide. It’s here, where I also still run our other projects – the Oklahoma Blues Hall of Fame and the D.C. Minner Rentiesville Museum.

In 1999, we received the Keeping the Blues Alive Award from The Blues Foundation for our efforts and contribution to music education and blues history. D.C. went on to being inducted into seven Halls of Fame, including the Oklahoma Jazz Hall of Fame in 1999 and the Oklahoma Music Hall of Fame in 2003.

D.C believed, “This is one of the few places where this history is still left,” and I work diligently and joyfully to keep the blues – and this rich history – preserved and alive in Oklahoma.

Blues singer-bassist Selby Minner toured for 12 years with her husband D.C. Minner and their band Blues on the Move before settling in Rentiesville, OK. She continues to perform and teach, and keeps the Oklahoma blues tradition alive through her weekly Sunday Jam Sessions, the Dusk 'Til Dawn Blues Festival, the Oklahoma Blues Hall of Fame (OBHOF), and the D.C. Minner Rentiesville Museum. For more information, visit: DCMinnerBlues.com.

References

Linda Reese, “Freedmen,” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=FR016.

Dr. Hugh W. Foley, Jr, “From Black Towns to Blues Festivals,” Funded by the Oklahoma Humanities Council and the National Endowment for the Humanities. http://dcminnerblues.com/?page_id=167.

Victor Luckerson, “The Promise of Oklahoma,” Smithsonian Magazine, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/unrealized-promise-oklahoma-180977174.

Larry O'Dell, “All-Black Towns,” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=AL009.

Hugh W. Foley, Jr., “Blues,” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=BL016.

MAKE SURE TO CHECK BLUES FESTIVAL MAGAZINE FOR MORE!

Exploring the Past through Ring Shout in Paule Marshall’s “Praisesong for the Widow”

Looking at black music and dance development in both the US and the Caribbean, Garcia identifies how Western cultural standards dominated discussions of culture, focusing on how racialized and sexualized bodies represented the primitive and savage through performance. Using theatrical productions, film, and performance hall recitals that “reproduced” African dance as historical “evidence,” viewers and scholars alike came to believe in Africa as a space that had not changed over the centuries, a haven for historical origins to which each member of the African diaspora could trace their roots.

BY CHELSEA ADAMS

Scholars and writers often use the idea or geography of Africa to indicate a return-to-roots journey for black people. The focus of the roots theme is a temporal shift, moving from the present to the past to discover ancestral roots, ceremonies, and cultural traditions that existed before slavery pillaged and plundered tribal lands. While recovering and remembering these people, cultures, and traditions is important work, it is often used as proof of African evolution from primitive to sophisticated cultural formations. Romanticism of the past often contributes to the idea that at its heart, black culture has a “wildness” to it, instilling Western ideas about blackness to the cultural mainstream. David F. Garcia states in his work Listening for Africa: Freedom, Modernity, and the Logic of Black Music’s African Origins, that scholarly intent to establish proof of racial equality by focusing on black bodies may have unintentionally damaged the cause of freedom.

Looking at black music and dance development in both the US and the Caribbean, Garcia identifies how Western cultural standards dominated discussions of culture, focusing on how racialized and sexualized bodies represented the primitive and savage through performance. Using theatrical productions, film, and performance hall recitals that “reproduced” African dance as historical “evidence,” viewers and scholars alike came to believe in Africa as a space that had not changed over the centuries, a haven for historical origins to which each member of the African diaspora could trace their roots. The “evolution” of culture for black people, then, could be said to come from the influence of Western European standards, as evidenced by the achievements of African Americans. Such racial categorizations were vital in maintaining racial boundaries, associating new, popular music styles with African origins to keep societal norms in place, associating blackness with the primitive and “wild,” whiteness with advancement and sophistication.

According to Garcia, perhaps the greatest danger of this scholarly and now even popular practice is “these contexts’ blockages that transform sound and movement from affective flow to, for example, African and European, black and white, or primitive and modern music and dance such that people are made temporally and spatially distant from each other” (270). While Garcia acknowledges that it may be impossible to rid discussion of historical timelines and individual motivations, he does advocate for a more complete look at art forms instead of segmenting them into categories of black and white, us and them.

Garcia’s approach is useful when reading Paule Marshall’s Praisesong for the Widow, which at first seems to fit in the category of the back-to-Africa novel, one that offers a temporal shift that takes its main character, Avey Johnson, from a US, middle class society to a Caribbean, working class society to recover her cultural origins. Avey is able to participate in a blending of cultures, traditions, and names, where “as the names transcend their original identity, they enter a space of total possibility. Their combinatory potential is now virtually infinite” (Boelhower 23). The spatial shift from the U.S. to the Caribbean, to the island nearest Africa, serves not as a complete return to ancient traditions, but as a space to view the diaspora and new cultural growth, both Avey’s own and other diasporic cultures. I suggest that what is at stake in Praisesong for the Widow is the recovery of individual identity and expression through a remembrance of family, rather than purely ancestral, traditions that bring Avey to self-fulfillment as she reorients herself to accept that culture should exist outside of the Western understanding of cultural binaries. The main recovery tools are African American art forms that come from a combination of cultural traditions in the U.S.

Avey receives cultural and spiritual renewal when she goes to the Big Drum ceremony on Carriacou. It is at the ceremonial proceedings that she reconnects with her Aunt Cuney through the ritual dance of the Ring Shout, and then her namesake, Avatara. Speaking of this event, where Avey becomes an active participant in the cultural traditions of the island, Lean’tin Bracks states, “The Beg Pardon dance is a crucial part of Avey’s island experience, for it proclaims that all are able to return to the celebration of ancestors, rituals, and traditions even after being lost” (116-7). Such a return through the Beg Pardon would not be possible for Avey, however, if it weren’t for Lebert Joseph and the elders in the group who sit in a sacred circle with “arms opened, faces lifted to the darkness, the small band of supplicants endlessly repeated the few lines that comprised the Beg Pardon, pleading and petitioning not only for themselves and for the friends and neighbors present in the yard, but for all their far-flung kin as well” (236). Without help, she would not experience the healing and renewal at the ceremony, because she does not know how to perform the ritual herself. The circle of elders holds significance for two main reasons: first, as Katrina Hazzard-Donald states, the sacred circles formed in ceremonial dances “represented a reality which connected one to the ancestors and reconfirmed a continuity through time and space” (196). The circle dance creates the opportunity for Avey to connect with her memories and her ancestral heritage to be filled with the strength and cultural knowledge. Second, as Bracks states, the intercession of the elders during the Big Drum Ceremony to offer up the Beg Pardon for their families and the world offers Avey an opportunity to see that “knowledge found in ancestral experiences is not only a function of historical memory as passed down from generation to generation, but also of current cultural practice that is available firsthand from those who are still alive. People of the diaspora can learn much from the living elders of their communities whose physical presence is a testament of their ability to survive and endure” (113). Before she attends the Big Drum Ceremony, Avey begrudges contact with the elders of black communities because they enshrined the very elements of black culture that she sought to run away from in order to fit into the middle class, white American mainstream lifestyle. At the Beg Pardon, she finally comes to understand and respect the role they play in such a sacred space, a crucial step to opening herself up to the wisdom they hold.

In fact, it is after the elders make intercession through the ritual that she can see someone who “seemed to be her great-aunt standing there beside her” (237). Like when Aunt Cuney used to take her to watch the Shouts performed in August, observing those “who still held to the old ways . . . slowly circling the room in a loose ring” (34), Avey watches the nation dances, her great-aunt spiritually with her on one side, Joseph Lebert with her on the other, explaining each dance they watch. Eventually, as is the nature of the circle dance, Avey must join in the performance. She spends time reflecting the open space they occupy begins to fill with dancers, expanding the longer the dancing goes on as more people join in the dance. The creole dances performed are a blend of many different African dance aesthetics that were shared across nations, meaning the space becomes more amenable to Avey’s participation.

When Avey finally joins the circle of older people and performs the Carriacou Tramp, she is performing a circle dance, the Ring Shout. The dances hold considerable similarities. According to Edward Thorpe, the dance “had certain affinities with the competitive Juba and consisted of a dance performed ‘with the whole body—with hands, feet, belly and hips’. The dancers formed a ring and proceeded with a step that was half shuffle, half stamp, and much pelvic swaying” (30). All the types of movement included in the dance are familiar to Avey, who has a long history of using the aesthetics of black dance as she danced to jazz music. According to Hazzard-Donald,

The shout ritual was the arena in which the motor muscle memory of African movement could be learned, sustained, relexified, and reborn eventually as secular dance forms. These forms would go on to become the famous African American dances that have circulated around the world; dances like the “Twist,” the “Black Bottom,” the “Pony” and, of course, the touch response partnering dance known as the “Lindy Hop” and all its various forms. (200)

The evolution of the dance allows for Avey to both be part of an older tradition and to be part of a new cultural tradition in the US. Even though Avey had not ever participated in a Ring Shout, she embodied the Africanist aesthetic as she performed the various dances done to jazz music, the Lindy Hop holding the greatest importance with its circular motion in partnership with another person. She holds a sense of ephebism and aesthetic of the cool as she slowly integrates herself into the dance. The elders in the circle dance, rather than try to teach her or push her out of the circle, welcome her in to work through the process and discover how her style of dancing can meld with their rhythms.

The moment offers a full realization of what it means to have African American heritage. Hazzard-Donald describes participation in the counterclockwise circle of the Ring Shout as engaging in “a ‘spirit-gate’ through which humans could connect to a higher spiritual reality” (203). That gate allows Avey access to what Hazzard-Donald calls “an intermediary religious form” which bridges the gap between traditional African religions and American religious forms (199). Barbara Frey Waxman discusses the importance of Avey’s dancing, because as

Avey carefully follows the rule of not letting her feet lose contact with the ground, a rule which metaphorically implies the principle of maintaining contact with her ancestral soil, her people, and their traditions. That is why Marshall calls this dance “the shuffle designed to stay the course of history” (250)—designed to subvert the drift of historical events that have prevented African Americans and Afro-Caribbeans from maintaining contact with their ancestral cultures. (98)

The dance she performs allows her to connect with her ancestors and reverence both her great-aunt and her namesake, Avatara; the dance allows her to finish healing from the spiritual malady caused when she cut herself off from her cultural heritage; and the dance allows her the opportunity to reclaim her past and look forward to the future opportunities she has to share her cultural knowledge with her own grandchildren. Avey is transported to Tatem and back to her childhood, where “under the cover of the darkness she was performing the dance that wasn’t supposed to be dancing, in imitation of the old folk shuffling in a loose ring inside the church. And she was singing along with them under her breath. . . . she used to long to give her great-aunt the slip and join those across the road” (248). In joining in the circle dance at the Big Drum Ceremony, she symbolically returns to Tatem to perform the Ring Shout with the church members, participating in a ritual she had longed to perform as a child but could not. The spiritual return to Tatem melds African-American and Afro-Caribbean traditions as everyone celebrates their shared African heritage.

It is this shared heritage on which Marshall ends her narrative, leaving readers to understand that the heritage Avey is to share is not purely African, but rather a rich mix of African and American heritage which make up her culture. Accepting the many influences of the diaspora is how to be self-fulfilled and a positive influence on continuation of cultural heritage. Doing so requires throwing out the linear, Western understandings of time and cultural evolution and replacing them with a circular understanding, which allows for the living and the dead to communicate shared wisdom and knowledge through generations as cultural tradition grows into new renditions and expressions of ancient values, which inspire new ways to deal with the present.

Works Cited

Boelhower, William. “Ethnographic Politics: The Uses of Memory in Ethnic Fiction.” Memory and Cultural Politics: New Approaches to American Ethnic Literatures. Northeastern UP, 1996, pp. 19-40.

Bracks, Lean’tin L. Writings on Black Women of the Diaspora: History, Language, and Identity. Garland Publishing, Inc, 1998.

Garcia, David F. Listening for Africa: Freedom, Modernity, and the Logic of Black Music’s African Origins. Duke UP, 2017.

Hazzard-Donald, Katrina. “Hoodoo Religion and American Dance Traditions: Rethinking the Ring Shout.” The Journal of Pan African Studies, vol. 4, no. 6, 2011, pp. 194-212.1.

Marshall, Paula. Praisesong for the Widow. Plume, 1983.

Thorpe, Edward. Black Dance. The Overlook Press, 1990.

Waxman, Barbara Frey. “Dancing out of Form, Dancing into Self: Genre and Metaphor in Marshall, Shange, and Walker.” MELUS, vol. 19, no. 3, 1994, pp. 91-106. www.jstor.org/stable/467874.

INTERVIEW WITH BILL “HOWLING MADD” PERRY

n Gospel, I was sitting on the corner one day when I was about 13 or 14 years old playing my guitar and a guy drove up and asked me if I wanted to be a part of their group. A local group out of Chicago. Which I said yeah cause it had always been my dream to play with a group, especially with a Gospel group cause I was raised up in the church. So that's how that venture got started. It got started with I guess you would call one of the lowest groups on the totem pole.

By: Shy Perry

Question- You've been in music for over 50 years, how did you get started in the Gospel and Blues field?

Answer- In Gospel, I was sitting on the corner one day when I was about 13 or 14 years old playing my guitar and a guy drove up and asked me if I wanted to be a part of their group. A local group out of Chicago. Which I said yeah cause it had always been my dream to play with a group, especially with a Gospel group cause I was raised up in the church. So that's how that venture got started. It got started with I guess you would call one of the lowest groups on the totem pole. But I made it all the way from there to the big times. With the Blues, I believe it was when we done the Apollo Theatre, we had a big show booked in Memphis, and when we got to Memphis, we got booked into the Lorraine Motel. We called up the promoters to let them know we were all in town and ready to play that night and he informed us that the show had been canceled at the last minute. So there we were checked in the hotel, no money, or nothing. It was still 3 or 4 days until the next show and I just decided to get up and put on some nice, clean clothes and walk down to the restaurant. I don't know what I was going down there for. I didn't have no money. I went down there anyway and there was Little Milton Campbell sitting there with a whole table full of food. And I stopped in my tracks and started drooling at the mouth. And the funny thing about it was about 3 or 4 weeks before that, we had been recording at the Chess Studios in Chicago and Milton was up there recording too, so we ran into each other a few times. So he recognized me as being a guitar player and he asked me if I wanted to play in his band. And I thought he was joking. But looking at me, I guess he knew I didn't have no money or nothing like that so he went in his pocket and pulled out a big roll of money, peeled off $100 and gave it to me in advance and said, I'll see you Sunday. I think that was on a Friday. He said we're leaving out Sunday morning early. I said ok. I left with the group that I was with, went and played 2 more shows in Huntsville, AL and Nashville, TN. After that show, I caught the bus back to Memphis to catch the band before they left and as the taxi was pulling into the Lorraine Motel, the band was loading up and was getting ready to leave. So I made it just in time. With Milton, I got a chance to be on stage with people like T-Bone Walker, Freddy King, a long line of people. There was a dancer called Wigglin' Ann and we backed her up one time. Wigglin' Ann was an exotic dancer. Then we had a break and I went to Chicago and while I was there, I ran into some people that was looking for somebody to be a writing partner with, a musician. I took the opportunity which resulted in my 1st record being recorded which was called I Was A Fool and from there the journey has been kind of here, there, and other places. You name it. So that was my entry in the Blues field and the funny thing about it was, I had this idea about Blues people and stuff, but when I left the Gospel field and went into the Blues field, I found out that I was leaving Harvard and rejoining kindergarden.

Question- How did you figure out that you wanted to play the guitar and sing?

Answer- I always knew that I wanted to play the guitar. Singing was a whole 'nother different story. I didn't think that I could sing. When I was about 12, I went to a show with my Uncle and brother to see Rufus Thomas and that was the changing point in my life. I had never seen a real, professional show before. So I wanted to be able to work a crowd the same way Rufus did that night, Through that 1st record of mine, it gave me the 1st opportunity to get in front of people and do my own thing. It took a while to get use to it, but after a while it becomes just like breathing. It comes automatically.

Question- What does the Blues mean to you?

Answer- Right now it means a lot to me because of the way it's going. It use to be that you had to have some talent to be a Blues player ot any kind of player as far as that concern. You had to know chords. And as BB King said one time, he didn't play a lot of chords. He played a lot of notes. I'm just in reverse, I play a lot of chords and I don't play that many notes. But I do here and there, not that I can't do it, I just rather play rhythm and that's what I started out doing and still love doing it today. But the way things are going, it's funny that the people that you run into calling themselves Blues singers and Blues players is just absolutely amazing and don't have a clue of what the Blues is really about. Anybody today that can learn how to play somebody else's songs is considered a Blues person if they got the nerve to stand up in front of people and do they thing. When you run into people that don't know the 1st thing about no kind of instrument, harmonica players that just blows into the harmonica with no style or nothing, just blowing into it. Guitar players that maybe know one or two chords, maybe. A lot of them don't even know how to tune their guitars. If you don't know how to tune your instrument, how can you know how to play it? That's the way I look at it. I know this is a whole different idea the way it was years back cause you really had to have some talent to be out here in front of people. In other words, people didn't play that back then, it seems like. Not unless they were sitting on a front porch somewhere.

Question- Since young, black people are not as involved in the blues as they use to be in the past, how do you feel about that? And do you think there is racism in the Blues?

Answer- Do I think? I Know that it's racism in the Blues! But that's everywhere, you name it. There are some younger players that's coming along and getting their name out there in a good way that's got talent, but that's some of the younger generation. The older guys just don't seem to care, that's my opinion. And looking back, I saw Blues disappear from the black scene basically. And I think it's affected our culture of blues. Yeah, cause it's taken it from where it was to somewhere that you can't really even recognize today in a lot of ways. The way it's portrayed to people, for us who created it, Blues and stuff like that, we get pushed back. Some really can't play. They can bang on their instruments, but that's about all that there is and to prove that point, a Grammy nominated Blues person, which I will not mention no name, was at a show. I was getting paid the same thing that that person was getting paid. The difference was, I had a pretty good house of people. That person only had one person listening to them. What can you say behind stuff like that? You got to go with the flow, I guess. It's one of the reasons why I try to stay as independent as I can because I'm not going to be used as somebody that's ignorant and don't have a clue about what the Blues is all about. Comparing Blues with plucking chickens and all that kind of stuff. What can you say, you know?

Question- You have a brand new album out called Perry Music Heals the Soul. Tell me about that?

Answer- That's been my dream to put the album out, a compilation, for a few years. Luckily, I own all my masters and stuff like that, so it's not hard for me to go back into the archives to pull out songs. The songs that I pulled out for this Perry Music Heals the Soul, every song on there, in my opinion, heal the soul and make you feel better. Make you want to get up and move and groove and dance. Have fun, juking all over the place.

Question- What are your future plans?

Answer- After we've taken this Heal the Soul CD as far as it will go, I'm going back to the archives to put out a part 2 compilation because we have quite a few other songs in the vault that we can go back to, that the majority of people that know us, know nothing about the different songs. That's going to be another project sonewhere down the road. A compilation part 2, Perry Music Heals the Soul. Whatever your ailments, down thoughts may be, Perry Music will bring it back up. Put it at 100 percent.

Question- What's your advice for up and coming artists?

Answer- Don't be stupid. Don't let somebody fool you into signing something that you'll never see a dime of the money that your music will bring in. Take a little time out and learn a little something about the music business. Try to stay as independent as possible because other than that if you don't know what you're doing, if you're stupid, then right away, you're going to be used. And you'll end up with a name that will represent something, but no money in your pocket. With me, if you ain't making no money with what you're creating, why deal with it? Why give it to somebody else then later on complain about what they did. No, what they did was took advantage of your stupidity. Anybody, young, old or whatever the case may be, learn a little something about what you're doing in this business and take it from there. Don't be stupid. Don't jump up and sign any piece of paper that somebody stick in front of your face telling you a whole bunch of falsehoods. Be careful out there dealing with folks because these folks are very slick. They know how to manipulate you through any type of weakness that you may have. There's people that I can name off that was manipulated through alcohol, women. In other words, give me the booze and women and I'm not concerned about nothing else. And then later on when you ain't got nothing, then you try to point your finger at somebody else, you can't do that. Learn a little something. Don't be so quick to sign something that somebody is sticking in front of you because what they're sticking in front of you could be taking everything you may make, in the years to come, away. That leaves nothing for you, nothing for your decendants, your heirs or whatever the case may be. Just to say that I'm out here doing this and not making any money, don't make any sense to me. That's my opinion. There's people I know that loves to do that.

Kesi Neblett - From Civil Rights Legacy to Netflix

I speak with the youngest daughter of Civil Rights Activists Charles and Marvinia Neblett, Kesi Neblett, who was born and raised in Russellville, KY, and has a fantastic story. She was also recently featured on THE Mole, a reality game shows that initially aired on ABC from 2001 to 2008 before being rebooted on Netflix in 2022.

On this episode, I speak with the youngest daughter of Civil Rights Activists Charles and Marvinia Neblett, Kesi Neblett, who was born and raised in Russellville, KY, and has a fantastic story. She was also recently featured on THE Mole; a reality game show that originally aired on ABC from 2001 to 2008 before being rebooted on Netflix in 2022.

Charles “Chuck” Neblett’s songs of protest resounded in southern jails, SNCC meetings, and freedom marches. As a child in rural Tennessee, Neblett remembered walking to his one-room schoolhouse and being sickened by the “fancy white school that was two stories tall.” His teachers motivated him, saying, “You’re Black, but you can make it. The one thing they can’t take from you is what’s in your head.”

On September 23, 1955, the murderers of Emmett Till were acquitted, and “it told me that I didn’t count in this country,” remembered Neblett. A little over two months later, the Montgomery Bus Boycott triggered something inside of him: “When I saw those Black men and women standing up to the system, it’s like I got religion.”

Kesi shares with us how she is living, continuing and writing her narrative!

Lady A: Pacific NW Black Blues

By Nascha Jolie

Lady A Photo Credit Leo Gabriel

Lady A, aka Anita White and The Real Lady A, announces that she and the band formerly known as Lady Antebellum filed joint motions to dismiss the trademark infringement litigation pending in the U.S. District Courts for Tennessee and Washington. The Parties have reached a confidential, mutually agreeable solution.

Lady A wants to thank all those that offered her encouragement, unconditional love, and support during this ordeal. She is especially grateful for her Cooley LLP law team, Brendan Hughes, Joe Drayton, Judd Lauter, Jane van Benten, and Natalie Pike, her team at Bradley Arant Boult Cummings LLP led by Junaid Odubeko, and for her Seattle producer and friend,

John Oliver III “who suggested seeking pro bono assistance from Cooley.”

Lady A appreciates their transparent communication, integrity, diligence, and tireless efforts. Their pro bono representation assisted Lady A, an independent musical artist, in protecting her name, amplifying her voice, and bringing awareness to the long history of Black artists being treated unfairly by those in the music industry.

Lady A’s ninth CD and latest offering entitled, Satisfyin’ is scheduled for release on February 7th, 2022 coinciding with Black History Month, Lady A is continuing to send out messages of hope and inspiration. Gio Pilato of Bluebird Reviews describes Lady A’s album as “… an eclectic, highly pleasing combo of Soul, Blues, Fusion, R&B and Funk that lifts your spirit throughout the whole duration of the record.” Please note the album can only be found by typing in the title of the CD, Satisfyin’ – Lady A.

With this chapter ending, and a new year upon us, Lady A -- The Real Lady A -- is grateful and excited about new opportunities the next chapter will bring. She looks forward to continuing to share her love of music and passion for music education through her involvement with the Rhapsody Project and Northwest Blues in the Schools. Her goal is to continue to uplift others and help to create positive changes for all those with whom she is honored to work in music and in her community. Always living by her motto: Be Blessed and Be A Blessing.

Black Lives, Names, Experiences, Work, Art – They All Matter.

PRESS RELEASE

STATEMENT FROM Lady A – The Real Lady A

The article and Interview start here

I reach Lady A on a Wednesday afternoon in early February at her home in Seattle. Despite an on-going pandemic, she has been busy performing locally, completing a brand new album which will be released at press time; and most recently settled a lawsuit that placed the Original Lady A on the front page of the news across the nation. But this bright sunny winter afternoon, Lady A is catching her breathing. She’s been busy working and performing gigs with her band all week now that the Seattle area has been recovering from recent snow storms.

“I’ve been gigging all through, COVID, it’s been wonderful,” she says. After the first few weeks of lock down so she and her producer came up with the idea to do pop-up performances around their city.

“You know, it was nice those first couple of weeks..you know, you got to work at home, but then it was like people were starting to go a little stir crazy. We had been working on a new CD, and everything kind of stopped, you know. So we started doing what was called pop-up concerts…We would just pop up in neighborhoods around the community and perform.”

Lady A says that the local storefront owners and food vendors supported their efforts by allowing them to either use their property or to set up in front of them. Before the mask mandates, the patrons could sit outside six feet apart and enjoy Lady A and her music while patronizing the local businesses. It became a great way to connect with the city, unite people during difficult times and to support the local economy.

Photo Credit: Dawn Johnson

From there, Lady A says that people would hire her and the band to play in their backyard for small private concerts. “Yeah, they sort of hired us to play in their back yard, just for a few people because you know, you couldn’t have a bunch of people…So we play for like 10 or 20 people depending on how big your backyard is. And that was fun and went on for a while.

“Then we did a lot of virtual concerts. I was very blessed to be able to do a lot of virtual concerts. And so I appreciate it. It really did work for me and my band. We did a lot of free things, but it didn’t matter for us…we called them unpaid rehearsals…”

Lady A says that she performed with variations of her band as well as in a duo with her good friend and song-writing partner, Roz, who also sings background for Lady A.

“I like to do different things within the music,” Lady A says. This variety is evident in her musical journey which began at home and blossomed in the church, like most blues singers.

Born Anita White, Lady A says that her roots are in Louisiana where her family migrated from, but she and her siblings were born and raised in the Columbia City and Beacon Hill neighborhoods in Seattle. She says that her family is musical where her parents and siblings sang and also played instruments. “My father was a drummer and so is my brother…you know we sing, but we don’t sing in church.”

Lady A began performing in the children’s choir at the age of five. She didn’t do any solo gigs until well into adulthood, but she continued performing in choirs at church all through her youth. At the age of sixteen, she became a choir director of her youth choir. “Our instrumentalists at the time..quit on us and it was the church’s anniversary…and I just got up and said, you know, we can sing by ourselves. I got up and taught the parts…”

Lady A says she continued directing her choir and others for years and got used to having her back to the audience. It took a good friend and the big karaoke scene in the 1980s for her to get used to performing in front of a big crowd. “…I was scared to death because I was always used to not having to look at the audience,” she says. Once over her fear, Lady A joined a Motown Revue and began performing as a background vocalist before making her way to the front of the stage through the years.

By the nineties, Lady A began fronting her own bands. She had her own band, Lady A and the Baby Blues Funk Band and she was also singing with many others. At some point, she was performing with a different band almost every night of the week except Sunday. These days, not much has changed, Lady A regularly performs and her band has evolved alongside her music.

What is the vibe of your new album, Satisfyin’?

“The vibe on this record is, because as I said music evolves, the vibe is Seattle’s soulful blues. So, when I grew up, my mother and grandmother listened to the blues and gospel. So I’ve always put a gospel song on every single album I’ve done, right.

“This album is an ode to the music that I remember, it’s the vibe that I remember when I was coming up. I was young and I was listening to the blues and none of my friends could understand why, but I did. But it’s also the soulful side of the blues. It’s that funky blues meets Kool and the Gang vibe.

“I still like the blues, so my blues is funky. This CD will give you a vibe if you want to play it in your car and turn it up loud!”

Who are your musical influences?

“Kool & The Gang, Bobby Rush, Millie Jackson, Mahalia Jackson, Johnnie Taylor, Earth Wind & Fire, Stevie Wonder, Bobby “Blue” Bland and Aretha Franklin.

“I love Aretha Franklin Sings the Blues album. That’s like my all time-favorite, besides her gospel stuff. She can really sing the blues. And Prince could sing the blues too, but you had to see him in concert.”

Where is your favorite place in Europe? What has been your most memorable concert or your favorite place to sing?

“Favorite location? That’s easy. I was so blessed to go on tour in my favorite place to go, Sweden. I’ve been to Sweden three times. I traveled to the Netherlands from there because it’s like going from Seattle to Portland. You can just get on a plane and hop over.

“I was doing a tour, the From The Soul Tour with the Top Dogs in Sweden..I was there for a month and it was during July which is also my birthday month. So, my birthday was right in the middle of this tour. I’ve played the Quantum Data Festival in the Netherlands.

“Fran Case invited me to come to the Netherlands. And he said just get on a plane and..pop on over. I'm like Oh, okay. So I did and I spent my birthday in the Netherlands, with friends of his and he invited his entire family to come and watch me perform..It was beautiful. And then the band that I played with in the Netherlands, a couple of them came up and so we just played music and did that. I flew back to Sweden to finish the tour…That's my favorite memory of performing there.”

What is your contribution to the blues in terms of keeping the legacy alive? How do you feel about the history of the blues and sharing that legacy in and outside of your music?

“I work with Northwest Blues in the Schools right here in Seattle. And it's just started up again through the Rhapsody Project, Washington Society.

“I am on the Board of Directors of the Rhapsody project, which is a music project for kids here in the Seattle area. I'm also a vocal coach and a mentor in that program.

“I’m a culture bearer which means that I talk about race, I talk about appropriation. It's like history man. I talk about it all the time anyway, even when it's not black history. We’re in Black History Month, but right here that represents who we are.

“Like history to me is about the shoulders that I stood on to get where I am, right? My ancestors my great grandmother, my great-great grandmother, my grandmother and my mother. They were important, are important people to me and my family.

“So I think that we have to remember that every decade or every generation has had to put up with something right? They help us get where we need to be. And sometimes we don't understand why they made the decisions that they did. Why they did what they did.

“But as I've gotten older, I've started to realize why some of those things happen. And I think that that's what I try to teach the kids that I work with snap right. I know you think your parents are lame, I know you think you know better, but they really are trying to do the best they can for you with the best they had.

“I have emails that I send out all year long. I love our history, but let's not forget [all parts of it]. We don't always have to talk about being slaves. Because we are no longer in the fields right now. We have progressed. We know we've progressed on our own right because we have to fight for everything that we had. So we don’t want to forge that, we want to celebrate our accomplishments.

“This year [in my diversity outreach], our theme is: Elevate and Celebrate, as we value our strengths.

“In my community work, I want people to understand the legacy we come from and to know that we come from Kings and Queens.”

“So we don't want to forget that and we want to celebrate our accomplishments and so our theme this year is elevated and celebrate, as we value our strengths. So I constantly you know, I mean my community work, and I I want people to understand the legacy that we come from Kings and Queens.

How do you feel about the release of your new album? What do you plan to do to promote it? Are you doing more virtual concerts? Are you planning on touring during the Spring and Summer months?

“Oh, yeah, I already have some dates. You know festival dates in Europe, already.

“I’m still going back to Sweden in April. The Blues Music Awards are coming up in Memphis, you know, so I’m going down to the Blues Foundation in Memphis.

“But that's all according to what COVID does. Because I have an 85 year old mother that I still need to take care of. I have to be safe round. You know, I'm very cognizant of what's going on. You know, I'm vaccinated. I'm boosted and all that, but still, I'm taking still taking the precautions. Because I've been around my band. We keep each other safe. We all have families that we have to go back to.

“It's gonna take some time, but I think we'll come out of it. You know, I understand people want to get out and about how do I miss traveling, but I'm ready. I'm ready.

“So I am looking forward to going on tour. And I'm still doing gigs. I'm doing a video shoot this weekend for AARP. And people still ask me to do virtual shows which is good, right?”

What are you most excited about for 2022?

“My new CD, Satisfyin’. I'm so excited. We launched it in Europe first. It launched in Europe on October 22.

“Oh, okay. Okay. So it's been out there and of course it gets leaked, you know, to the US so which is fine. But the so the DJs in in Europe have been playing it like crazy. And I am so grateful. And now the DJs here in the States are playing it because of course they've got it already through my publicist.

“And I'm so excited about it coming out because I think people are going to enjoy the CD.

“Every one of my CDs is a progression and growth. Okay. And when I'm doing absolutely it really is and I'm really like I still love my very first CD. I still love my very first CD blues in the key of me still love it to this day. Not saying I don't love the other ones, but I do but this one this particular one satisfying the last one I did I'm like Wow, is that me?”

What can listeners look forward to in this latest project? How have you progressed as an artist?

“I think I'm coming into my own on every CD that I'm doing and this one is going to be fun for the springtime when it comes out.

Did you write any of the songs on this album?

“Yes, I wrote a good portion of it. I have. I've written like about five or six songs. I’ve co-written with my Seattle producer and play brother, John Oliver the Third. He's written some and I’ve co-written with my backgrounds there.”

Have you always written your own songs?

“On my first album, Bluez in the Key of Me, I wrote two songs on there. Back then, I think that I didn’t believe that I was a good writer. On my second album, How Did I Get Here, I wrote three songs on there, and John Oliver and the Third Group did the rest of them. But ever since those albums, I’ve been writing.

“Because when people write for you, you have to really feel that connection to what you’e saying on the song. When other people write for you, it’s great. It can be a great song, right? But if you don't identify with it, or if you don't feel it, it's really hard to sing it. I mean, it's great to sing other people’s songs but I really do enjoy writing my own songs.”

Are you glad that the legal matter is now over? What were the terms of your settlement? Are you still Lady A? Can you keep your stage name?

“I’m happy, I’m pleased with the outcome. Yes, I’m still Lady A. I can still use the name.

“I can’t speak about [the settlement] now, however, I have released a press statement. If you would print the statement in full, I would be so pleased. Other publications did not…”

John Wesley Work III - composer, ethnomusicologist, educator, and choral director

In this broadcast, Todd Lawrence and I discuss the scholarship and work Of John Wesley Work III and the newly launched Award named in His honor. The AFS African American Folklore Section is proud to issue the first call for submissions for the new John Wesley Work III Award

Published By: Lamont Jack Pearley

In this broadcast, Todd Lawrence and I discuss the scholarship and work Of John Wesley Work III and the newly launched Award named in His honor. The AFS African American Folklore Section is proud to issue the first call for submissions for the new John Wesley Work III Award, which the section has launched to honor and spotlight applied folklorists, ethnographers, and ethnomusicologists who actively focus on the research, documentation, recording, and highlighting of African American culture through performance, written word, and music in their scholarly works.

Our Featured Guest is Fisk Alumni George ‘Geo’ Cooper, a pianist, composer, and music educator. While at Fisk, he was a member of the world-renowned Fisk Jubilee Singers.

Fisk Alumni George ‘Geo’ Cooper

The AFS African American Folklore Section is proud to issue the first call for submissions for the new John Wesley Work III Award, which the section has launched to honor and spotlight applied folklorists, ethnographers, and ethnomusicologists who actively focus on the research, documentation, recording, and highlighting of African American culture through performance, written word, and music in their scholarly works.

The prize is named for John Wesley Work III, a composer, ethnomusicologist, educator, and choral director devoted to documenting the progression of Black musical expression. His notable collections of traditional and emerging African American music include Negro Folk Songs and the Archive of American Folk Song in the Library of Congress/Fisk University Mississippi Delta Collection (AFC 1941/002). The Stovall Plantation recordings for the Library of Congress where the world is introduced to blues legend McKinley Morganfield, aka Muddy Waters.

In honor of Work, this award is offered to celebrate and encourage African American traditional cultural expression and galvanize folklorists, ethnographers, and ethnomusicologists of color to participate in the documentation of African American folklife.

TO SUBMIT FOR THE AWARD, PRESS THE LINK THAT WILL TAKE YOU TO THE AMERICAN FOLKLORE SOCIETY PAGE!

Blues Narrative - Mr. Waltho Wallace Wesley

Mr. Waltho Wallace Wesley, a descendant from the Muskogee Creek and Seminole Nations. A Life long resident of Indian territory in present-day Oklahoma, and ‘Black’ Indian historian.

The Blues Narrative – “Blues People, COVID19 & Civil Unrest” is a first-person account of the life and experiences of African Americans, Black Indians, Pan-Africanists (individuals and families), aka The Blues People, during this moment in history where there’s a global pandemic, quarantines, protests, and riots happening ALL AT THE SAME TIME and in real-time. In this episode, I speak to Mr. Waltho Wallace Wesley, a descendant from the Muskogee Creek and Seminole Nations. A Life long resident of Indian territory in present-day Oklahoma, and ‘Black’ Indian historian.

Stagolee and John Henry: Two Black Freedom Songs?

Published By: The African American Folklorist Newspaper (Editor Lamont Jack Pearley)

Written By: Jim Hauser

Are the African American ballads “Stagolee” and “John Henry” freedom songs? What I mean is, Do they express racial resistance, protest, and rebellion? I’ve been researching both ballads for well over a decade, and I believe the answer to this question is “Yes.” A key thing necessary to really understand these songs is to realize that they are both about black manhood and that they both originated and became extremely popular during a time when African Americans were denied their manhood—and their humanity–by the dominant white majority. It also helps to have some knowledge of black history and what everyday life was like for African Americans in the Jim Crow era. If we possess that knowledge and keep in mind the importance of black manhood in both ballads, then we are better equipped to “hear” the resistance, protest, and rebellion when we listen to recordings of these ballads. And maybe we might even see the possibility that Stagolee’s fight with Billy over a Stetson hat and John Henry’s race against a mechanical steam drill could be symbolic of the African American fight for manhood and the struggle for black freedom. But before taking a closer look at these ballads, I want to bring your attention to the quote below.

These songs didn’t come out of thin air… If you sang “John Henry” as many times as me– John Henry was a steel-driving man / Died with a hammer in his hand / John Henry said “a man ain’t nothin’ but a man / Before I let that steam drill drive me down / I’ll die with that hammer in my hand.” If you had sung that song as many times as I did, you’d have written “How many roads must a man walk down?” too. —Bob Dylan (from his MusiCares Person of the Year speech, February 2015)

Let’s start by looking at an important function of ballads. According to Paul Oliver in his book Blues Fell This Morning, “A ballad symbolized the suppressed desires of the singer when he could see no way of overcoming his oppression. It is a vocal dream of wish-fulfillment.” He goes on to say that the ballad singer “projected on his heroes the successes that he could not believe could be his own.” So when a black musician sang about Stagolee fighting Billy to get back his stolen Stetson hat, exactly how did that battle symbolize fulfillment of the singer’s wishes? And when a black worker sang about John Henry challenging a steam drill to a race and defeating it, what unreachable success was that worker projecting on his hero John Henry? Could it be that the fight over the Stetson and the race against the steam drill symbolized something of great importance to them and had something to do with their freedom? It certainly seems possible to me. Let’s investigate that possibility by taking a closer look at each of the ballads.

Let’s begin with “Stagloee.” According to folklorist and educator Cecil Brown, in his book Stagolee Shot Billy, to understand the meaning of Stagolee “we must search for the symbolic meaning behind constantly recurring motifs such as the Stetson hat.” He explains that at the time the ballad originated in the late 19th century, African American men wore Stetsons as symbols of masculinity, status, and power. In other words, the Stetson was a symbol of manhood, or to be more specific, black manhood.